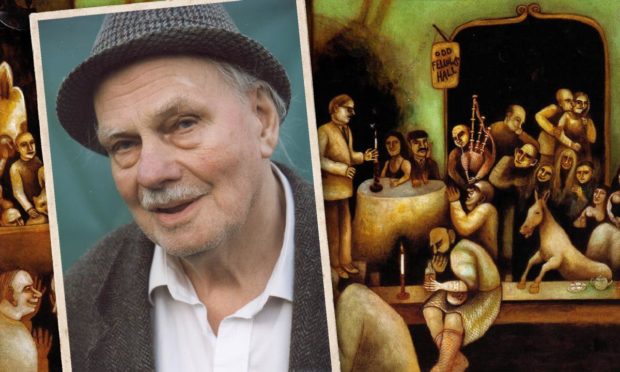

Seventy years ago in the Oddfellows Hall in Edinburgh, a few ordinary people – crofters, farmers, fishwives, labourers – got up to sing the songs of their homelands in the Highlands and north-east.

They blew away their lowland audience, and unwittingly sowed the seed of something that would flower into the Scottish folk revival of the 1960s.

The occasion was the 1951 Edinburgh People’s Festival Ceilidh, organised by songwriter and tradition bearer Hamish Henderson; Norman Buchan, who would go on to be shadow minister for the arts; and Glasgow teacher Morris Blythsman, left-wingers from the Labour movement.

They had decided that a week-long People’s Festival should be organised as a necessary counterweight to the lofty highbrow events of the Edinburgh Festival.

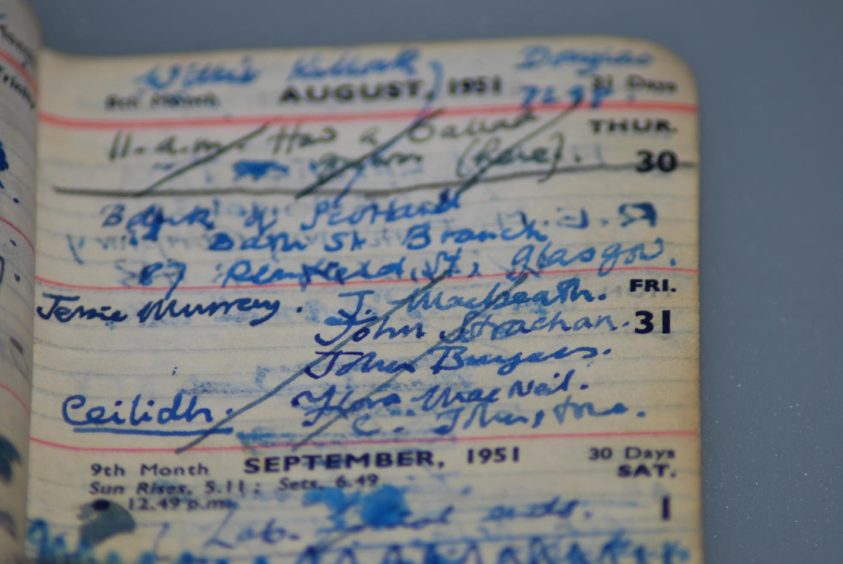

A fundraising ceilidh concert was held on the Friday night, featuring Gaelic singers Flora MacNeil and piper Calum Johnston, both from Barra; four north-east singers, Buckie fishwife Jessie Murray, Portsoy travelling labourer Jimmy MacBeath, and John Strachan from Crichie.

They simply stood up and sang unaccompanied in a way lowlanders thought had been lost in the mists of time.

It was the first time Scottish traditional folk music was performed on the public stage.

“The lowlanders were amazed,” says songwriter/story teller Ewan McVicar from Inverness.

“To them it was a Scottish folk revival, but the tradition had never stopped in the north-east and the Gaeltacht.”

On hand to record every song was American singer/ethnographer Alan Lomax, and the recordings were squirreled away for decades, with no platform for their airing at that time.

Local voices really matter and the People’s Festival Ceilidh was one of the first events to demonstrate that in a meaningful way.”

Steve Byrne

To celebrate the 70th anniversary of the gig, and in the spirit of the times, Ewan has assembled a website where the seminal ceilidh can be relived through Lomax’s original recordings of it.

Each song from 1951 is set off by a recording by a modern artist, with Gordeanna McCulloch, Daibhidh Stiubhard, Anne Lorne Gillies, Malinky, Blanche Wood, Furrow Collective, Barbara Dickson and Archie Fisher, and Christine Kydd in the line-up.

The Edinburgh People’s Festival Ceilidh was hosted annually for three more years.

Ewan said: “In addition to putting folk music on the public stage, it was heavily political, associated with communism and Scottish self-determination, which would ultimately be the festival’s downfall after 1954.”

Because of the Communist ties of several members of the People’s Festival Committee, the Labour party declared it a proscribed organisation, and the trades unions withdrew support.

But the public performances of music previously only heard in intimate gatherings had sparked something that couldn’t be quelled.

Ewan said: “After it came a groundswell of enthusiasm for Scots song, house ceilidhs, concerts and campfires.

“The first wave of folk clubs began in 1960, with young people learning and singing the songs through lyric booklets and recordings.

“Dozens of artists up to the present day have express the debt owed by Scotland to ceilidh organiser Hamish Henderson and the original singers by sharing their own versions of songs performed at the event.”

Ewan asked modern folk singers to contribute their versions of the songs to set alongside the 1951 performances on the website, including Steve Byrne with his band Malinky, and the Irish singer Francy Devine.

Arbroath man Steve said: “Presenting the material from the 1951 event in this way, with modern equivalent recordings of essentially the same songs, although these things do vary a bit, such is the folk tradition, is a really clever way of showing the 1951 ceilidh’s relevance still to this day.

“It’s important to view the event as part of a longer process involving many other events and people in creating what’s known as the folk revival.

“And as time has moved along, inspired by the approach of Henderson and Lomax, and the 1951 ceilidh, I’ve very much come to the view that local songs, people singing about where they come from, songs that relate to the places in which they live and work are as important as they’ve ever been in terms of their usefulness for community confidence and working especially with schoolchildren and their sense of place.

“Local voices really matter and the People’s Festival Ceilidh was one of the first events to demonstrate that in a meaningful way.”

Steve was part of the cataloguing team at Kist o Riches/Tobar an Dualchais, and he worked for a time on the Hamish Henderson papers, now held at Edinburgh University.

He said: “I had a real insight into Henderson’s collecting process, his correspondence, and his communication with Alan Lomax.

“So I’ve always been something of a scholar-performer, and in my professional life I’ve taken some of the songs, and the singers who performed them, and studied, shared and celebrated them with audiences round the world.”

For Steve, Alan Lomax’s influence in terms of the Scottish scene cannot be underestimated.

“He was significant in terms of helping to support the work done by the likes of Hamish Henderson, who was the ceilidh’s compère and himself a noted collector of Scottish folksong and an early fieldworker at the School of Scottish Studies that was founded the same year.

“It’s important to note that there had been other recordings going on in Scotland before the ceilidh took place but Lomax helped to put the Scottish tradition in the global context of the work he was doing, in his words, ‘to record the world’, for Columbia Records.

“I didn’t know Lomax personally but was privileged to visit the archive in New York and be given a tour by his daughter, folklorist Anna Lomax Wood.

“As well as being a singer, I’m also a folklorist, so one of my favourite documentaries of all time is Lomax the Songhunter by Dutch filmmaker Rogier Kappers.

“It is a brilliant insight into Alan’s philosophy of recording local communities across the world as part of the richness of the human folk experience, and his idea of cultural equity – that all cultures deserve their share of the airtime.

“I follow that principle today in my own work.”

Ewan said: “The 1951 festival was judged a resounding artistic and cultural success, but suffered ‘a fairly serious financial loss’ of £50.

“The 1952 festival, however, ran for three weeks, with the Oddfellows Hall again the grand finale.

“But the involvement of the Communist Party in the organising of the festival was its downfall, supporters made nervous by McCarthyism dropped out and the 1954 festival was the last.

“The effects of the ceilidhs nevertheless rang out loud and long in Scotland’s central belt.

“Hamish Henderson in Edinburgh began his life-long task of recording and writing about Scotland’s oral culture.

“In Glasgow Norman and Janey Buchan organised concerts, and he and Morris Blythman edited lyric books and booklets that inspired young singers all across the country.

“Remember, that this was very much a city-based revival enthusiasm; in the North East and the Gaeltacht they had never stopped singing and honouring their traditions, not just song but piping, fiddle-playing and country dancing.

“Alan Lomax, up until 1957, continued to mine his Scottish recordings for influential commercial discs and radio and television programmes.”

Steve Byrne added that the ceilidh brought a note of authenticity to the scene.

“It made a statement on behalf of traditional, local singers across the country against the Harry Lauder version of Scottish music, it was more authentic, you might say, and in its own way was Hamish Henderson’s riposte to the scepticism of his sometime flyting partner Hugh MacDiarmid, who had his doubts about the value of folksong at the time. “