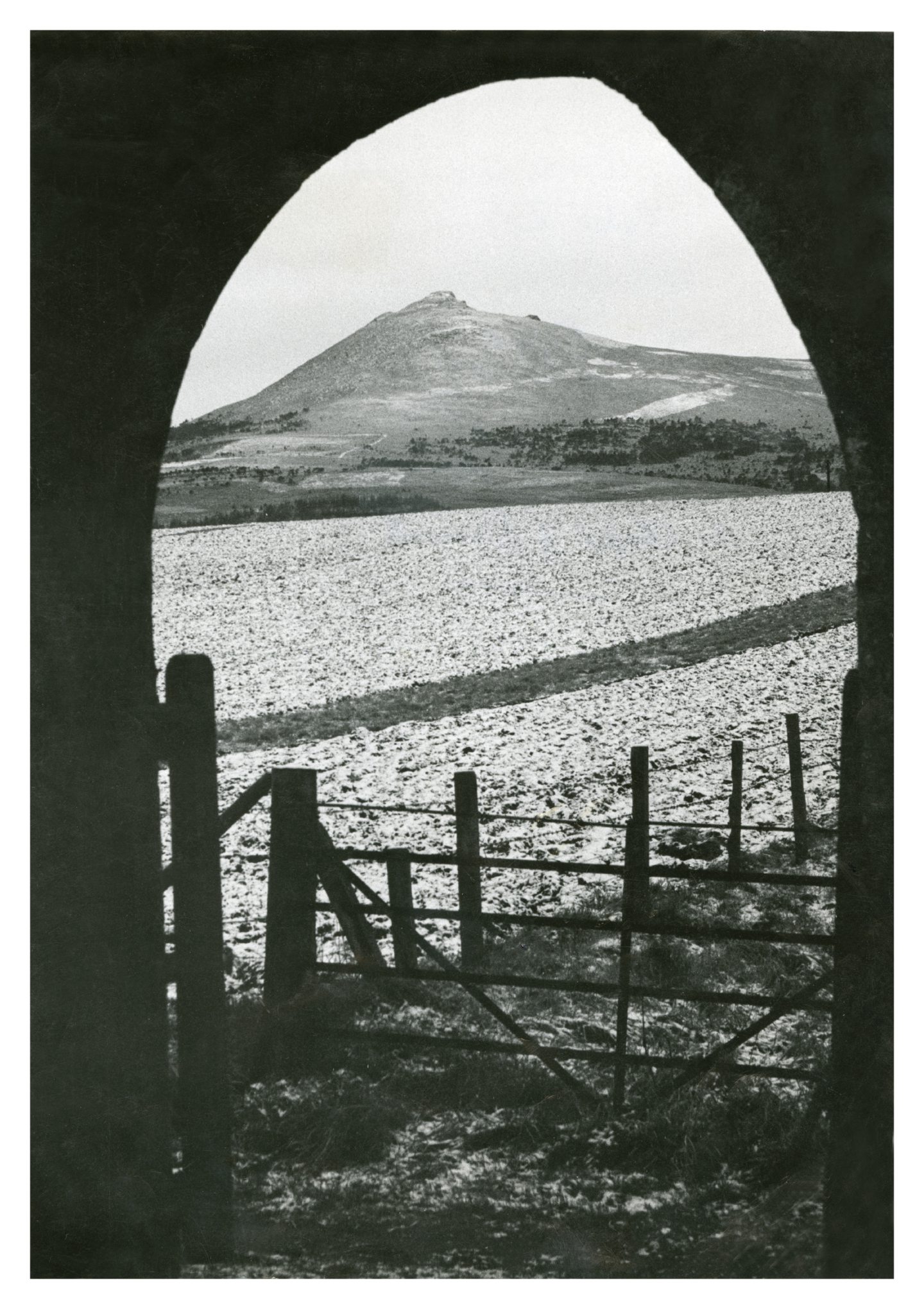

For many of us in Aberdeenshire, the sight of Bennachie means home – but for the colonists of the 19th Century, the hill really was their home.

Mither Tap’s damson-purple, heather-clad silhouette rising from the the horizon is a welcome sight for weary travellers heading home to the Garioch.

A much-loved hill trodden by thousands of walkers a year, it’s hard to imagine now that a community carved out an existence on the brutal, bare face of Bennachie.

But settlers made the hill their home, until local lairds took over the hill forcing many families to leave.

Now, a play has been commissioned to bring the tale of the colonists back to life to mark the 50th anniversary of the Bailies of Bennachie.

A colony on the slopes of Bennachie

Before 1895, Bennachie was a commonty or free forest – its rich lands were shared among the locals.

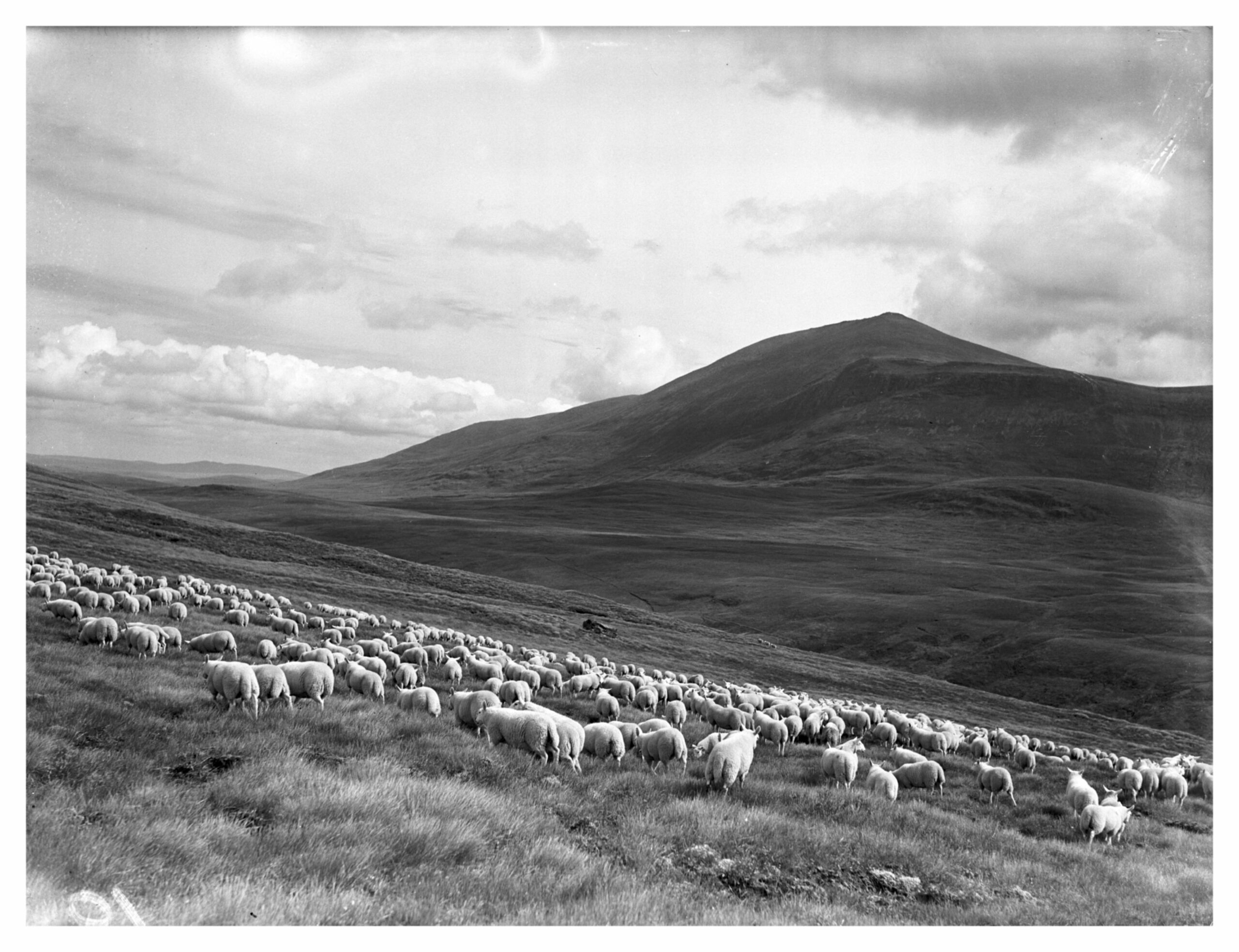

This meant people could graze cattle and sheep, cut peats and take stones for building and heather for thatching.

In 1801, the first settler built himself a house on a grassy area on the south-east slope of Mither Tap, and the colony was begun.

With just a pick and shovel, he established a home on the left bank of the Clachie Burn.

Within 60 years, around a dozen households had raised crofts from the bare, hostile hillside, built from the granite beneath their feet.

Among the colony of around 140 people, there were the Littlejohns, Mitchells, Findlaters, Christies, Beverleys and the Essons.

Entirely self-sufficient and living 700ft up the hillside, the colonists had a tough existence on an unforgiving landscape.

Many worked as labourers, masons and thatchers; they quarried, grew vegetables, raised animals – and operated their own illicit whisky still.

The homes were generally two-roomed, thatched dwellings, built from stone and clay with one door.

Nine local lairds claimed Bennachie as their own

But not everyone was happy about this marginal community living rent-free on Bennachie – particularly local landlords.

Others felt that by staking a claim to the communal hill, it undermined the spirit of the common land.

In the early 1800s, Aberdeenshire had a shortage of land to work and the tilling of infertile ground was encouraged.

The industrious colonists took poor ground, and through sheer toil, cultivated opportunities as well as crops.

However, their time living off the land was short-lived.

Nine neighbouring lairds decided to take ownership of Bennachie – and the colony.

They divided the commonty of Bennachie among themselves, simply drawing straight lines across a plan of the hill.

And on March 5 1859, the division of the land was approved at the Court of Session in Edinburgh, and the lairds claimed sections for their own estates.

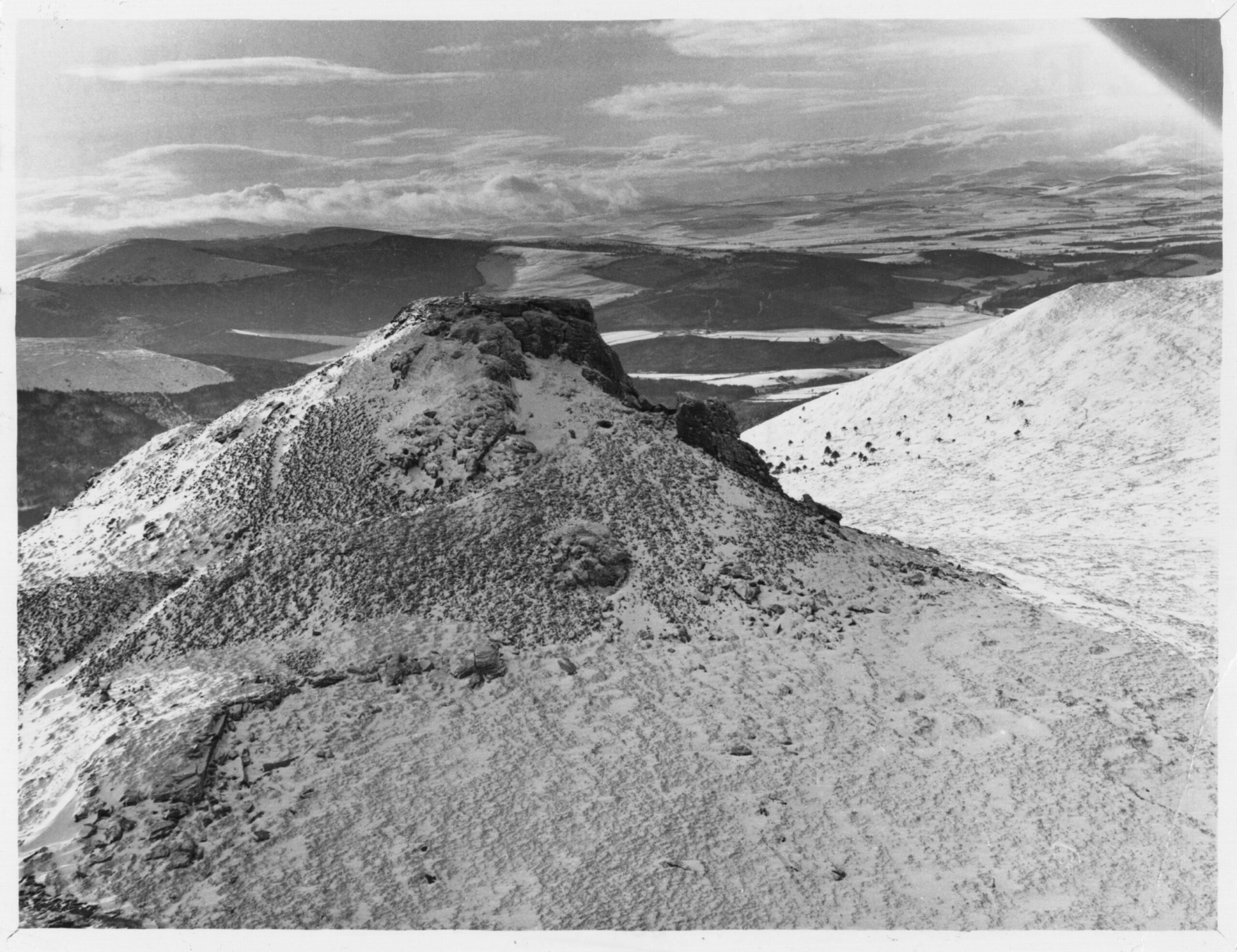

The estates’ initials were scored into the granite on the top of Mither Tap – B (Balquhain), P (Pittodrie) and LE (Logie Elphinstone) – known as the Thieves’ Mark.

Overnight, the Bennachie colonists lost all ownership of their homes, with no right to stay in them or even work their land.

Colonists forcibly evicted from crofts

The division meant the colony became part of the Fetternear Estate and the settlers had to pay rent or leave.

Some families clung on, but those unable to pay were evicted, while others were forcibly removed.

Estate factors knocked down masonry causing buildings to collapse, and evidence found through excavations showed that some may have been burned down.

The most famous of the colonist families was the Essons, who all came from surrounding parishes.

In the 1861 census, after the hill had been taken over, three Esson families were still recorded as living on Bennachie.

John Esson signed a lease agreeing to pay £2.50 per annum for his own house and cultivating his land.

But colonists Hugh and James Littlejohn stopped paying their rent, and in 1878 they were evicted.

Their furniture was removed and parts of their crofts were knocked down by a sheriff’s officer from Inverurie and two policemen.

The elderly Alex Littlejohn was carried out of his croft in his bed.

This forcible removal of colonists was compared to the Highland Clearances, and to this day is known as the Rape of Bennachie.

The last man living on Bennachie

John Esson, who had lived on Bennachie since he was five, was still living there upon his death aged 70 in 1891.

His youngest son George, who spent time in America, then took on the family croft with his wife Mary Ann Knight.

George, although educated and literate, became a mason and dyker, and carved out a living on Bennachie and surrounding estates.

Sometimes he would walk 20 miles for a job, boarding during the week and returning to his croft at weekends.

Despite his perceived simple existence, like his father, George took a great interest in antiquities, local history and current affairs.

His wife died 1937, and although frail himself, George continued to live on Bennachie.

In final letters before his death in 1939, he had mentioned the politics of Europe as war crept ever nearer.

When George, the last man living on Bennachie died at the age of 75, the colony died with him.

George was buried in Chapel of Garioch kirkyard, which looks out on Bennachie, and the Reverend Alexander Campbell conducted the ceremony.

He had a poignant epitaph added to George’s grave: “George Esson, descended from the first, and himself the last of the colonists on Bennachie.”

Bailies of Bennachie were born

The Forestry Commission acquired land on Bennachie in 1938 and still manage the hill today.

But by the 1970s, the commission wanted to strike a balance between conservation and recreation.

New paths were created to manage walkers, but oil brought an influx of people to the area and more ramblers to Bennachie.

Fearing an environmental threat to the hill, a meeting was held at Inverurie Town Hall in 1973, and the Bailies of Bennachie were born.

The group was set up to preserve amenity and folklore, to become guardians of the hill, and the memories of those whose lives were so intertwined with Bennachie.

The aims of the society set out at that meeting remain as pertinent today. Prevention of litter and vandalism; maintenance of footpaths; the study of rocks, flora and fauna, and the preservation of Bennachie’s unique place in north-east folklore.

But it was also felt important to preserve and collect its ballads, customs, legends, poetry and art.

Honouring the colonists, the Bailies have created a living history project, with a 19th Century kailyard as part of the colony trail at Bennachie.

New play about Bennachie colonists

And now, half a century later, a new play about the colonists has been commissioned by the Bailies to commemorate their 50th anniversary.

Peter Stock, chairman of the Bailies of Bennachie, said: “Excavation of their homes and research into family history has thrown new light into this important and dramatic episode of local history.

“For the 50th anniversary the Bailies wanted to tell this history in a new way to a different audience”.

‘The Hill that was a Home’, written by award-winning writer Alan Bissett, will be performed in English and in Doric by young people from the Inverurie area.

Mr Bissett said he hopes to bring national attention to the colonists’ plight and the struggle to maintain their way of life “in the face of rapacious greed from landowners”.

Many of the cast come from Mitchell’s School of Drama, with experienced theatre-maker Rhona Mitchell directing the play, with musical direction from Alisdair Sneden.

Rhona Mitchell, whose drama group is marking its 40th anniversary this year, described the production as “ambitious and exciting”.

She added: “The young cast are enjoying finding ways to bring the story to life and do justice to the lives of the Bennachie colonists.

“We hope that local audiences are going to respond really well to this drama with music.”

- Performances of The Hill that was a Home will take place at the Garioch Heritage Centre in Inverurie, from July 5-9 2023.

Conversation