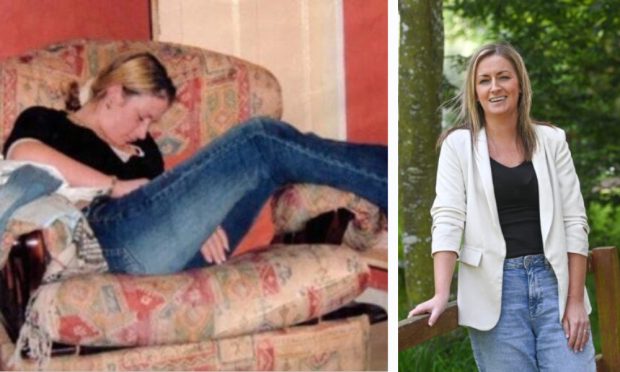

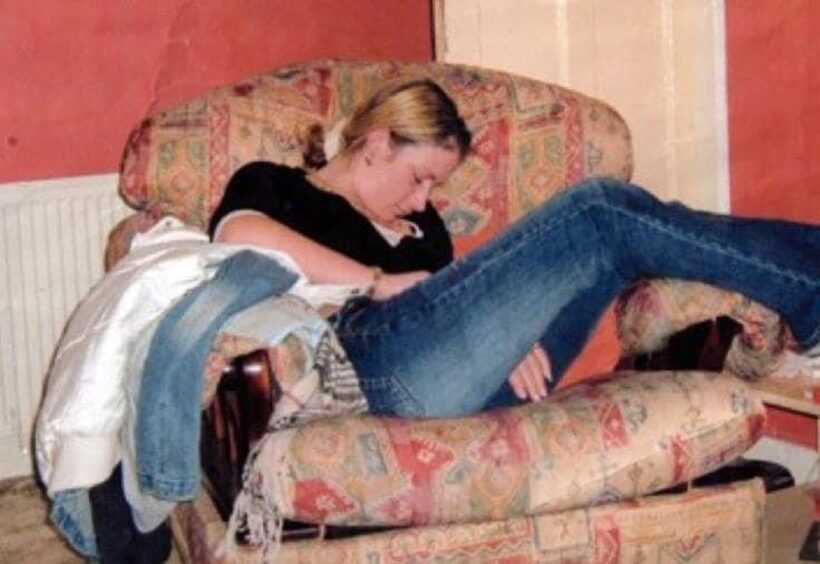

It’s in the monotony of the daily grind – making packed lunches and being a taxi for her children – that Aberdeenshire mum Julie Innes derives the greatest joy. For decades earlier, addicted to heroin and a regular face in Aberdeen Police Station, her “normal” was strikingly different.

Writer Lindsay Bruce sat down with Julie, now a prison chaplain and street pastor, as she shares her story of being “loved back to life”, an ethos which now underpins her own life and work, here in the north-east of Scotland.

A frighteningly early entry to world of drink and drugs

By the time she was 13, the same age as her own daughter now, Julie Innes – then Julie Milton from Northfield – had already acquired a taste for cheap cider and amphetamines.

“Honestly, when I look at my daughter, and think what my life was like at the same age, It’s terrifying.

“We had already started going to nightclubs by 12 and 13. Any interest we once had in school was gone by the time we came back after the summer holidays to start second year. From then on, life was all about the weekend. School just got in the way.”

Julie was banned from some exams and spent schooldays smoking cannabis

Julie grew up in a bustling home. One of five, she lived with her mum and step-dad, attending Cornhill Primary before moving on to St Machar Academy.

“They were happy times. I didn’t get into what I did because of unhappiness,” she says. “And it wasn’t just me. We were all looking for a good time, all the time.”

Growing up between Northfield and Mastrick Julie’s attendance at school was so sporadic, and her behaviour at times so disruptive, she was “banned from some exams.”

“I mean, I was never there. And when I was we were all smoking cannabis and mucking about. I came away with three standard grades but I wasn’t bothered. I just wanted to leave school and party. There was no ambition.”

Turning to heroin at the age of 15

Now 40, Julie says she remembers being offered heroin for the first time at 15.

“I know my mum was worried about me. I was going off the rails and wouldn’t listen. Around the age of 15 was when I first tried heroin but it made me that sick I had no intention of using it again really.”

However, a series of unforeseen personal challenges saw Julie spiral into a depression. Desperate, she turned to heroin once more. By the time she neared her 17th birthday her mum enlisted help from their GP. Julie started daily doses of methadone.

“I hadn’t quite hit rock bottom yet,” she explains, “but I was about to.”

‘I thought I would die like this’

It’s hard to imagine that this warm, articulate woman, who recently met Princess Anne, could ever have lived the life of someone brought low by addiction.

“How far I have come is a testament to the people who helped me along the way,” Julie says. “Because I might not have survived otherwise.”

An insatiable desire for heroin on top of her methadone saw Julie’s life go from bad to worse. Taking anti-depressants and smoking crack as well, her friendship group suffered multiple losses as “one chum after another” overdosed and died.

“I thought I was going to die a drug addict.

“I had no hope. And the guilt of what I was putting my family through was eating me up. It seemed pretty certain that my life would end the way it had for so many others.”

A chance to hope found on a church pew

But that was until she found herself in the pews of a church one Sunday evening.

“I’m not from a church family so it was all new to me. I’m not even sure why I went in that first time.

“I would go along, sometimes I would fall asleep, but the thing I couldn’t get over was people being interested in me.

“They sat next to me, some invited me round for Sunday dinner. I was just thinking, ‘what are they all about… who would have me in their house?'”

It was through attending King’s Church, then on King Street, Aberdeen, that Julie first heard about Teen Challenge, a rehabilitation centre in Wales.

“A lassie stood up one week and shared her story of being an addict and then going to this place and coming off the drugs. It was the first time the penny dropped that I didn’t need to bide in addiction forever.”

How Julie was given life back through rehab

On May 2 2005 Julie made the trip to the faith-based residential rehab centre in Wales.

“My family didn’t even go holidays outside of the Shire. Wales seemed like the other side of the world.

“I took my last dose of methadone and off I went.

“I was so sick of my life I figured I could handle whatever came next.”

What followed was an “horrendous” period of withdrawal lasting weeks. Encouragement that “it wouldn’t always be like this” kept her going until she awoke one morning realising she had slept – for the first time in years – without the aid of any drugs.

“It was like coming back to life. For years – and it was years – I was numb. All I did was get up, go to the chemist, find money for a fix… never noticing anything around me.

“I remember one day asking if the trees had always been that green. I never appreciated how beautiful anything was before. My eyes were opened.”

Faith for the future

But for every moment of wonder there was also the “carnage” of taking responsibility.

“I was having counseling which made me look at myself and take responsibility for everything I had done, and everything I put my family through.

“A lot of letters and phone calls, and a lot of time passed before relationships were restored. There was so much going on in my mind – but I knew I couldn’t change for good on my own.”

Julie remembers the pastor at her church inviting the congregation to be “changed by God”.

“That was the beginning of my new life. And the start of me having faith, myself.

“Though I found it easier to believe that God could forgive me, than it ever was for me to forgive myself.”

Back from the brink and a happy marriage

Julie completed the 11-month rehabilitation programme, then stayed on as a volunteer for five more months. During that time she had the opportunity to visit India as part of an outreach team and on her return she was offered a full-time job working with young women coming into the Welsh centre.

“I loved it. I think when you know you’ve been pulled from the brink you have a passion to help others,” she said.

After some years an opportunity came for Julie to return home to the north-east.

She became friends with Paul Innes, HMP Grampian chaplain – who then ran Solid Rock Cafe in Fraserburgh – and the pair tied the knot in 2010.

Together they have two children, Hannah 13 and Joel 10, and Julie has now almost 15 years of post-rehab experience helping others.

“It went from being a job to a calling. I really think I’m here to love people back to life,” she explains.

Inspiring others

It’s a career she’s given her life to.

After a decade in a Teen Challenge base near Peterhead, she then helped set up an outreach initiative for sex workers in Aberdeen.

Though she relished “the normal bits of life and just being a mum” she jumped at the chance to become involved with prison chaplaincy too. Four years later – and now the recipient of a Butler Trust commendation for recovery work she established in lockdown, she’s embarking on further challenges.

“It will never not be surreal, that I get to do this. I believe God uses all the hurt and pain to help me help others.”

As well as her chaplaincy she’s now also working with Sacro, supporting people in the community post-prison, and inspiring others within her sector.

“I’m loving it actually. It’s a bit like going on a journey with a person, helping them rebuild their life. Which is exactly what people did for me.

“I also had the opportunity to talk to management recently. My message was for people who get discouraged when they see the same people experience the same recurrent problems over and over.”

Change is possible

Immaculately dressed, with beautiful hair and make-up, Julie is the embodiment of hope.

“I just keep saying, that was me. It wasn’t straight forward, it’s never easy, but people can change. With the right support, there is a different future.”

As we bring the interview to a close I ask if she’s still in touch with any of her friends from “back in the day.”

Facebook’s good for that, she says. But not everyone has made it.

“Is there any sense of survivor’s guilt?” I ask.

“There is,” she concedes. “That’s why I’m sharing my story. If one person sees this and thinks ‘I don’t need to bide in addiction any more’ then me surviving has been worth it.”

Conversation