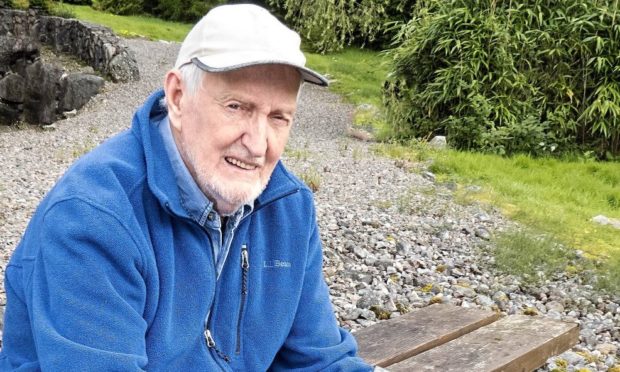

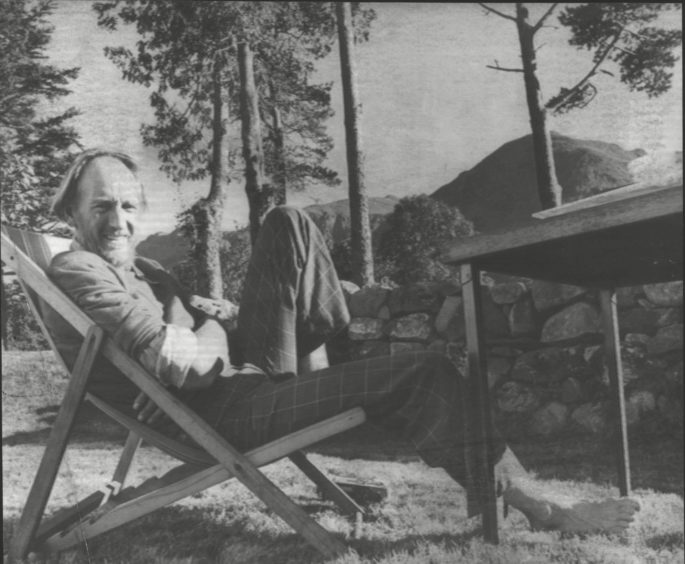

Hamish MacInnes, one of the world’s most famous mountaineers, has died at his Highland home, aged 90.

And one of his colleagues said the Scottish hills would be “darker and emptier”, now that the man with the nicknames the Fox of Glencoe and MacPiton has gone.

The remarkable Scot, who was climbing on the Matterhorn as a teenager and was involved in Sir Chris Bonington’s successful Mount Everest Southwest Face expedition in 1975, was a pioneering figure widely regarded as the father of modern mountain rescue.

His inventive mind was the catalyst for a number of initiatives such as the Search and Rescue Dog Association and the Avalanche Information Service.

He made an attempt to climb Everest in 1953 and is credited with inventing the first all-metal ice-axe and a lightweight stretcher, widely used in mountain and helicopter rescue.

Sad news from Scotland today, Hamish MacInnes was a true pioneer and history-maker of mountaineering who will be sadly missed.https://t.co/1BtGvze8C9

Photo: Hamish was kind enough to loan us his original prototype Terrordactyl for a number of years. pic.twitter.com/Tj62ZFOHfk

— Mountain Heritage Trust (@mtn_heritage) November 23, 2020

A sense of wanderlust, thirst for adventure

During his far-travelled and eventful life, he worked with some of Hollywood’s biggest names, including Clint Eastwood, Sir Sean Connery and Robert De Niro on such films as The Eiger Sanction, Five Days One Summer and the Mission.

But the redoubtable character, who was born in Gatehouse of Fleet in Kirkcudbrightshire in 1930, had many strings to his bow, was captivated and fascinated by the allure of his country’s myriad high places and was never happier than when he was tackling a fresh challenge in the Cuillins or the Cairngorms.

A sense of wanderlust, thirst for adventure and desire to break down barriers was in his DNA. His father served in the Chinese police in Shanghai, before joining the British Army and the Canadian Army during the First World War.

As the youngest member of a large family, MacInnes was left to blaze his own distinctive trail and proved the wisdom of the adage that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains.

At 17, he built his own motor car. There were few problems which confronted him, on or off the peaks, whch he could not negotiate. Or, at least, not until the latter stages of his life.

In 2014, Mr MacInnes suffered a urinary tract infection which left him suffering from delirium and he was ‘sectioned’ into a psychiatric hospital in the Scottish Highlands.

He made multiple attempts to escape from confinement, including scaling up the outside of the hospital to stand on its roof.

Eventually, after recovering from the illness, he was left with no memory of his former life, but, true to type, he rallied from adversity and made a poignant return to the spotlight.

The Final Ascent

In 2018, a documentary film was produced for BBC Scotland, titled Final Ascent:The Legend of Hamish MacInnes.

Introduced by his friend, Sir Michael Palin, it recounted the story of MacInnes’s life and achievements, and how he used archive footage, his photographs and his many books to “recover his memories and rescue himself”.

Mr MacInnes, who received an OBE and BEM, and was inducted into the Scottish Sport Hall of Fame in 2003, died at the weekend at his home in Glencoe.

‘The Scottish hills are darker and emptier today’

John Allen, the former head of the Cairngorm Mountain Rescue Team, paid heartfelt tribute to his former colleague.

He said: “The Scottish hills are darker and emptier today following the passing of the iconic and universally respected Hamish McInnes.

“In addition to being a world-class mountaineer, Hamish had a lifelong interest in mountain rescue.

“Today, the stretcher he designed is well known as the McInnes Stretcher and is used by many mountain rescue teams both in the UK and throughout the world.

“In 2000, when the Cairngorm MRT opened their new rescue base rescue in Aviemore, we were looking for a celebrity to perform the opening ceremony and, in my view, there was only one possible candidate. Hamish was delighted to fill that role. He was generous with his praise and we were honoured he gave us his support.

“His name and memory will live on in all our hearts and minds.”

Members of the Lochaber Mountain Rescue Team also paid tribute. In a statement online they said: “The team would like to like to pay its respects to Hamish MacInnes OBE who has passed away today. We have worked closely with Hamish and Glencoe MRT for well over 60 years.

“A mountaineering legend, he gave much to Scottish and worldwide mountain rescue. From the rescue stretcher we use today, the MacInnes Mark 6, to the invention of the Pterodactyl ice axe we have much to thank him for. Always willing to advise he cut a major figure in our world and that of more general mountaineering.

“We would like to celebrate his achievements and remember the countless numbers of folk saved on the mountains due to his innovation and tenacity.

“Hamish RIP from all your friends here in Lochaber.”

Expeditions around the world

Hamish MacInnes took part in many expeditions to various parts of the world, including the first British ascent of the Bonatti Pillar of the Dru in the French Alps.

In the Himalayas, he embarked on four expeditions to Mount Everest.

The first of these, in 1953, was his attempt to be the first to conquer the world’s highest mountain, and was an audacious two-man affair which went ahead without permission, visas or money, and whose strategy depended on living off food abandoned by a Swiss expedition the previous year.

However, when MacInnes and his friend John Cunningham arrived at base camp, they found that a young New Zealander, Edmund Hillary, and his Sherpa companion, Tenzing Norgay, had beaten them to it.

Undaunted, they took part in an ascent of the previously unclimbed Pumori nearby, though that proved unsuccessful.

In 1975, he was deputy leader of Chris Bonington’s Everest expedition, which included such renowned figures as Dougal Haston and Doug Scott.

They conquered the south-west face, but MacInnes was nearly killed in an avalanche.

Asked what it was like to be caught in a situation like that, he was typically phlegmatic.

He said: “It certainly concentrates the mind.

“Sometimes, it happens quite suddenly and without warning while, on other occasions, I have felt as if the whole mountainside was slowly slipping away beneath me.

“There is nothing you can do, but go with the flow. I’ve developed a technique in falling.

“I quite deliberately bring my hand up to cover my mouth, so that when I eventually come to a halt under the snow, I will at least have a little space in which to breathe.”