In this free preview of our special subscriber-only series, we tell the inside story of how the drugs problem exploded in the North-east in the early 1980s.

Part one: The early 80s and the rise of Brian Beattie

(Listen to this section as audio)

Pink Floyd’s Another Brick in the Wall was still number one and Aberdeen FC were starting the second half of a season that would ultimately see them crowned champions of Scotland.

January 1980 heralded the start of a new decade. A decade that was to see huge social upheaval in politics, fashion and the music scene. But it would also see the arrival of drugs to the North-east of Scotland, bringing with them organised crime, violence and a dramatic shift in police tactics across the region.

The decade had started in a relatively quiet fashion. Police in Aberdeen saw little in the way of mass drug taking, large-scale addiction or organised drug dealing. Sure, cannabis was smoked but only on a small scale, while amphetamine was seen from time to time.

But class A drugs, such as heroin and cocaine, were rarely in circulation. One former Grampian Police drugs squad officer, who began his police career in the late 1970s, said: “When I joined the police my impression at that time was that the only drugs of any consequence were cannabis or amphetamine: speed.

“There was no heroin, cocaine and we didn’t even know what crack cocaine was. LSD was around but it was on the way down. It had trended itself out. Cocaine and heroin were your big city drugs.

“You had the odd heroin addict but they were known. They were so unusual you knew who they were. “They would have to travel to the likes of Liverpool to get their drugs. It wasn’t a lucrative trade. They were just supporting their own habits.”

It was a bit back-of-the-fag-packet back in the day: let’s get a warrant, kick the door in and see what we get.”

Policing at the time reflected the size of the problem and the tactics were straight-forward, if rather rudimentary. Officers would hear drugs were being used at an address, get a warrant and raid the place.

The officer added: “It was a bit back-of-the-fag-packet back in the day: let’s get a warrant, kick the door in and see what we get.”

But by the early to mid-80s the drug scene started to change. Some experts cite the de-industrialisation of Scotland as being partly to blame, creating high unemployment and a generation of kids with little to look forward to. A ripe market for heroin being farmed in Afghanistan, cannabis from North Africa and, eventually, cocaine from the jungles of Colombia.

But Aberdeen was more complicated. And that was down to oil.

The former senior drug squad officer said: “The city became cosmopolitan quite quickly with the oil money coming in, Americans coming in. I’m not blaming Americans but you had lots of different people coming with different philosophies and previous exposures to drugs.

“I can’t prove this but when you look at oil drillers, back then you had people working 24 hours and 48 hours on the trot. You’ve got to be crazy if you didn’t think they were taking amphetamines. If you go back through the history of drugs even the military would give paratroopers and pilots amphetamines.

But Aberdeen was more complicated. And that was down to oil.

“The oil, the growing wealth and the disposable incomes led to a good marketplace which was rich for picking.”

As the market grew, dealers became more organised, setting up along the lines of any other business.

The principles were simple: establish a network of trusted people you can sell to, establish a source for your product, then make sure you work from “a mother stash” in a rural location so, if you’re caught, you don’t lose most of your supply.

And then there was the tick list – a dealer’s paper record of who bought what and how much they paid or owed. In an age before mobile phones and WhatsApp, the tick list was like gold dust to drug squad officers. Find the tick list and you were on to a winner.

Forces were also starting to understand that they needed to use informants to build intelligence on the growing number of dealers. Arrest someone, go down to the cells, have a chat, offer them some cigarettes and get to know them a bit. Then you might start to get some information that could lead you up the drug dealing chain.

In 1982, in Aberdeen, one man sat at the top of that chain. Brian Beattie, dubbed the city’s first drugs baron.

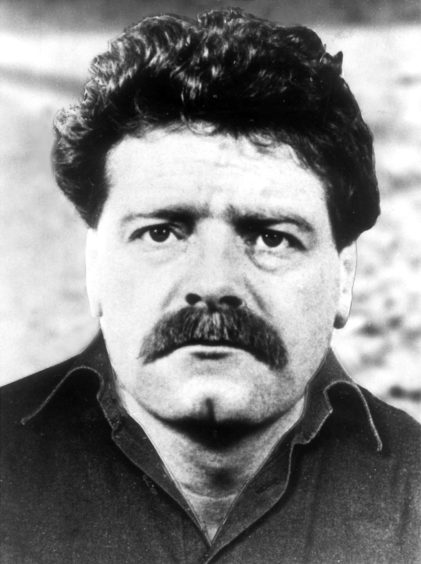

BRIAN BEATTIE

Beattie, from Kincorth, was a man already at odds with the law, known by police for poaching salmon. But Beattie, the eldest of a family of three boys, soon discovered there were other more lucrative ways of making money – drugs.

His empire started slowly, with cannabis and speed his products of choice. However, it wasn’t long before he was selling heroin; highly addictive therefore highly profitable.

His local bar, The Covenanter, became his base – and business was good. At the time Aberdeen had very few heroin addicts but Beattie made sure that figure started to rocket.

Beattie, who cut a striking figure with his walrus moustache, was almost idolised by teenagers in his local area who became part of his mob and his customer base. One officer involved in the operation to bring him down said: “He was quite articulate, smart and clever. He was basically able to manipulate them.

“He was probably the kind of guy — and he wouldn’t be the only one involved in drugs to be like this — who, if he had turned his hand to legitimate business and commerce, he probably would have been pretty good.”

Beattie sold drugs at his local, at his home in Kincorth, the community centre, nearby houses, and waste ground while the nearby Gramps grassland was the perfect site for hiding his “mother” stash.

As business grew, Beattie’s gang included Graham ‘Pot’ Duncan, a 31-year-old who went from a well-paid oilman, fitness fanatic and a happy marriage to heroin addict and Beattie’s minder.

Beattie had contacts across Scotland and as far south as London, where he’d send addicts to pick up his gear then transport it back up the road to be sold on the streets of Aberdeen. He was at his peak between 1982 and 1984, selling hundreds of thousands of pounds of drugs each year.

He was also known for his luck in evading justice. He and Duncan once turned up late to a drugs meet at the Holiday Inn in Bucksburn, shortly after police had raided the premises arresting London couriers and finding drugs stashed in a hotel room.

But, as with all empires, his domination began to crumble, and when it finally did it did so in spectacular and bloody circumstances with his henchman Pot Duncan the root cause.

Duncan was a human time-bomb prone to explode for no reason. One retired officer said: “I always found him reasonable to deal with but he seemed to change. I suppose, maybe, it was his drug abuse. He certainly started to get a reputation for being short-tempered.

“He could blow quite quickly and was a powerful guy. He was certainly prone to violence as time moved on.”

Duncan was a human time-bomb prone to explode for no reason

But one man wasn’t afraid. George Ritchie had stood up to Duncan and his boss, having seen the devastating impact drugs had on his own two sons. After a year or so of feuding with Beattie, he finally incurred the wrath of Duncan.

Four days before Christmas 1985, after going out for a drink in his local bar, he was knifed to death by Duncan as Beattie, who was on his way to deliver Christmas presents to his ex-wife, looked on.

Duncan had pulled Ritchie from his seat in the bar, before stabbing him three times with a carving knife. The fatal blow punctured a lung and an artery, leaving Ritchie slumped between some pool tables.

Beattie, Duncan and another man all denied murder when they appeared on trial at the High Court in Aberdeen in March 1986. But in a sensational move, Duncan changed his plea to guilty while Beattie and his fellow accomplice had not guilty pleas accepted by the Crown.

However, the North-east’s first Mr Big didn’t walk free as he had confessed to a string of drug dealing charges. He was jailed for 17 years while Duncan was given life for murder.

Beattie’s void was quickly filled by others. A retired officer said: “Others replaced him, the market was bigger and the opportunity to make money was bigger. If he hadn’t been caught he would have continued, grown and expanded.

“But you can’t really do that when you are in prison, which is one argument that prison works.”

Subscribe to access more

If you enjoyed part one of our History of Drugs then don’t miss the remaining five parts (available here to subscribers). We look at how the North-east’s heroin epidemic hit in the 90s, how guns and organised crime arrived on our streets, the communities that fought back, and reveal one mother’s heartbreak over the death of her son.