A Highland mansion goes on fire in February 1914 and it’s immediately assumed it must be the work of militant suffragettes.

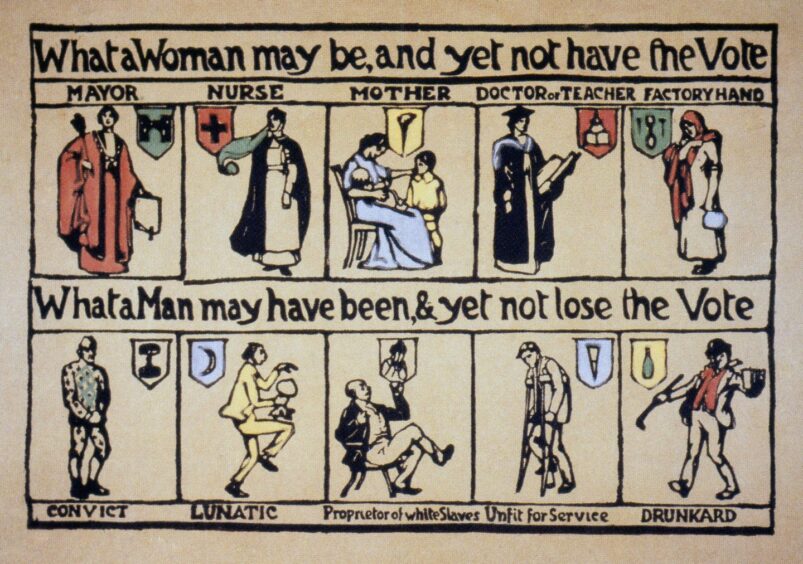

From a 21st-Century perspective it’s hard to image why women would have had to go to the lengths of bombing and burning buildings to get the right to vote.

Hard also to imagine that it’s only 94 years since women were fully enfranchised in this country.

It didn’t happen overnight, in fact it took nearly a century of campaigning.

In 1832, Mary Smith, from Yorkshire, led the first women’s suffrage petition to be presented to Parliament.

After tireless years of campaigning and minor advances came the Representation of the People Act 1918, entitling privileged women to vote—those over 30 owning land or premises with a rateable value of £5, or whose husbands did.

All men over 21 got the right to vote at that point, whether or not they had property.

The battle was only partly won

In 1928 came the Equal Franchise Act where women over 21 were able to vote, and finally had the same voting rights as men.

It was a long, hard-fought, hard-won battle, and Highland women were just as much part of it, taking militant action on their own territory.

One night in February 1914 a magnificent villa known as Hazeldene in Tomatin was burned to the ground.

The headlines concluded that it was the work of suffragettes, with little to support this conjecture in the actual story.

“Suffragettes are again suspected of being responsible for the destruction of another handsome Highland mansion,” they proclaimed.

Mansion closed up for winter

The house belonged to a Mrs Macdougall who had closed it up for the winter months while she went to stay in Inverness.

“A neighbour who kept an eye on the buildings saw nothing unusual on the Friday evening,” reported The Courier, “but about three o clock in the morning a flare was observed in the sky and it was seen that Hazeldene was ablaze.

“The alarm was promptly raised, but when the neighbours gathered it was found that fire had a grip of the entire edifice.

“Soon the handsome buildings were in ruins, the roof falling in.”

The damage was estimated at about £8,000, almost £2m in today’s money.

Futile police search

Police arrived from Inverness, about 20 miles distant, and carried out a search to no avail.

The whole matter seemed shrouded in mystery – but here were the possible culprits, suggested the papers: “It was said that a mysterious motor car with a lady and gentlemen had been seen in the vicinity a day or two before.

“Following so soon after the fires in the unoccupied shooting lodges in Perthshire, the blame is laid at the door of the suffragettes.”

Militant suffragettes had been accused of arson attacks on three mansions in Upper Strathearn a few nights before, causing outrage in the public and fear in the servants.

The Crieff Woman’s Suffrage Society denied all connection with the militant suffragettes, and there seems to have been some evidence that militants were behind the fires.

Arson and bombing campaign

Since 1912, suffragettes across Britain and Ireland had been orchestrating a bombing and arson campaign, which had seen buildings burned down, and some fatalities, and which only came to a halt on the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914.

Suffrage for women was far from achieved at that point, but the suffragettes vowed to pause their campaigning to aid the war effort.

On the night of the Hazeldene fire, Highland Railway pointsman at the Slochd declared he had seen a car pass southward at about 3 on the morning.

The police were making every effort to trace the car and its occupants, the public were assured.

Tramps also in the frame

Another theory was that there were tramps about who might have taken shelter for the night and accidentally set the house on fire.

“No trace of them can now be got,” said the papers.

The police set in train precautions to ensure the safety of other fine mansions in the district.

They included Kyllachy House, belonging to Lord Kyllachy, and the stately Moy Hall belonging to the Mackintosh of Mackintosh.

It was full of great art and Jacobite treasures.

Mackintosh decided to protect his property with a dog guard.

He had a large number of sporting dogs kept in kennels close by, and they were distributed around the mansion to raise the alarm if anyone approached, night or day.

Other properties from Inverness to Perth followed suit.

There were also shooting lodges at Daviot, unoccupied but possibly with a caretaker or servant in residence.

Watch was set on these properties, with “Inverness-shire police leaving nothing undone to unravel the mystery of the fire,” said the papers.

There’s no record of how the investigation proceeded and whether suffragettes were behind the burning of Hazeldene, but they had certainly been getting more militant in the Highlands.

Suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst toured the Highlands in 1909 to raise money for their war chest, picking up more than £45, more than £6,000 today, in visits to Grantown and Kingussie.

For an insight into the times, much admiration was reported for Mrs Pankhurst’s young lady chauffeur.

We don’t know her name, but as the press reported, after only two months driving experience, “she has something to be proud of, inasmuch as she drove her car north through Drumochter Pass and Dalnaspidal at night.

‘Equal to all emergencies’

“She is equal to all emergencies, and a torn tyre does not disturb her equanimity.”

Admiration soon gave way to slight facetiousness in the report: “There was considerable stir in Strathspey when it was discovered that Miss Adela Pankhurst [daughter of Emmeline] had left her hat behind. The hat was not a small one, and much excitement was caused by the search for a cardboard box large enough to hold it.”

Among many other suffragette disruptions there were scuffles in churches, fund-raising for the cause at the Braemar Games and fears that the activities would disrupt the Highland and Agricultural show in Paisley.

Dornoch’s Historylinks museum has an account of two reported incidents of militant behaviour in the town, one in 1912 and one in 1913.

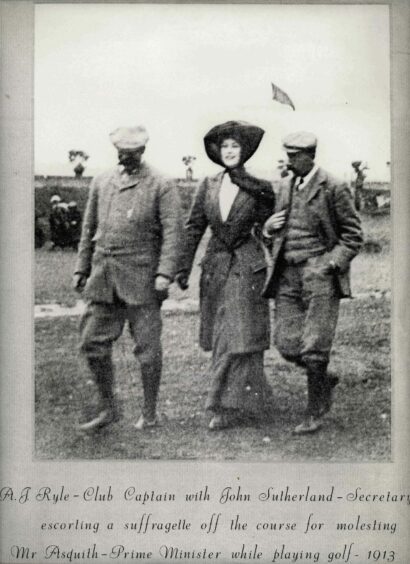

Both were on the Royal Dornoch Golf Course and were carried out by members of the WSPU.

Targeting male dominated sports was a typical WSPU tactic.

In the first incident Lilias Mitchell and Elsie Howie attacked the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith and the Home Secretary Reginald McKenna as they golfed.

The incident was kept quiet in Britain but was reported in the newspapers in America.

In 1913 Asquith was again attacked while golfing this time by a local lady, either Jessie or Agnes Gibson, sisters who lived in ‘Briarfield’ which overlooks the course.

Miss Gibson knocked off the Prime Minister’s hat and was escorted off the course by Mr. Ryle and Mr. Sutherland.

You might enjoy:

The Pankhurst sister sent from Aberdeen to Australia with £20 and a one-way ticket

Conversation