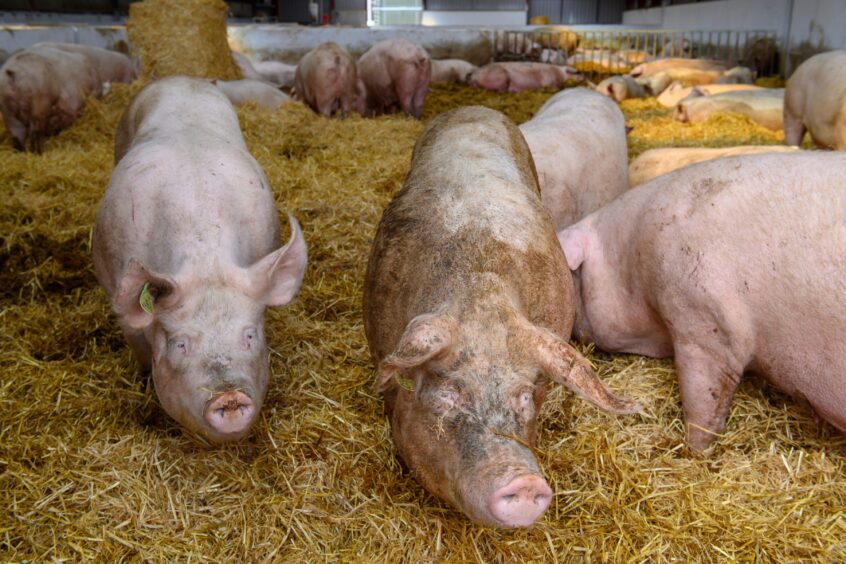

Where on earth have all these animals been hiding?

That was my first thought after Aberdeenshire pig farmers Ben Lowe and Gregor Bruce told me they kept about 900 sows between them.

I’ve lived in Ellon for more than 20 years and their farms are within a few miles of my doorstep. But I don’t recall ever seeing such large numbers of swine in the fields nearby.

There’s a lot more to farming than cows and sheep

The scale of these two large pig farming operations – and there are much bigger ones elsewhere in Scotland – got me thinking about the pork industry north of the border.

It’s fair to say that when we think about livestock farming, it’s usually cows and sheep.

We’re more likely to see these animals in the fields around where we live. Pigs have a lower profile.

Gregor told me there’s also often a bigger disconnect between pigs and the products.

Picking up a pack of sliced ham in the supermarket can seem far removed from the living animal it comes from, he said.

Aberdeenshire pig farms part of big pork production sector across Scotland

But pigs are clearly big business in Aberdeenshire and many other parts of Scotland.

Ben and his wife, Harriet, run HB Farms – an intensive pig and arable enterprise.

Their land consists of Newseat of Dumbreck, an arable farm on tenancy from the Aberdeen Endowment Trust, and Pitmillan Farm, which is home to 450 breeding sows and a finishing unit.

Ben and Harriet bought into pigs in 2021

Ben grew up in North Berwick, near Edinburgh, and worked on farms from the age of 14. He went on to obtain an honours degree in agriculture at Scotland’s Rural College in Edinburgh, while also building up a flock of 150 ewes.

After studying, he completed a traineeship as an agronomist with Agrovista and now works as an agent for the firm, working with farmers all over the country.

He moved to the north-east 10 years ago and married Harriet – a farmer’s daughter – in 2023. They’d bought their pig unit two years earlier.

300 new piglets a week

They now farm 970 acres, growing cereals and producing straw for the animals. Their enterprise produces about 300 piglets a week which are taken through to finishing at about 265lb. It employs a handful of people.

With 20 sows giving birth every week, on average, the work is hard and the hours long.

And there’s another new life to think about – as I write, Harriet is also due to give birth.

It’s all about the genes

Ben gave me a fascinating glimpse into life on their farms, explaining how the sows are impregnated using artificial insemination.

This means there is more control over the genetic mix – the sows are a cross between Large Whites and Landrace pig breeds, which is the norm for this livestock in Scotland.

It also helps to ensure the sows and their offspring stay disease-free.

“If we get anything wrong, it could be disastrous.” Ben added.

There are four boars on the farms, but it seems their role – through scent – is to keep the females frisky and “in the mood”.

I was amazed by how much data goes into a modern-day pig enterprise.

And this is delivering results – Ben told me the sows are producing 50% more pork than they would have done 15-20 years ago.

Stats for everything to do with pigs

There are stats for everything from how the mums give birth and the health of their piglets to how fast the animals grow. “We need to know as much as possible to make this business work,” Ben explained.

But there are huge challenges, as well as fears.

Pig farmers share the same concerns about input prices, as well as the impact of inheritance tax and National Insurance changes, as the rest of the agriculture industry.

But Scottish pig producers are highly dependent on the abbatoir at Brechin. This facility, owned by Browns Food Group, is the main pork processing site in Scotland.

Should anything happen to it, Ben and Harriet’s pigs would have to endure a journey of more than seven hours to get to the next nearest slaughterhouse. This is beyond what is acceptable under modern-day welfare standards for the transportation of farm animals.

Circular economy credentials

Ben and Harriet are proud of their circular economy credentials – growing most of its own animal feed, with manure going back into feeding the crops.

But there’s an economic imperative here too – doing this makes them less exposed to volatile feed prices. They can also sell feed on the open market when prices are strong.

Pork prices are relatively steady just now, in stark contrast to just a few years ago when a combination of Covid, Brexit and gas issues hit the market extremely hard, Ben said.

African swine fever threat

The ever-present threat of disease, particularly highly contagious African swine flu, which is often fatal for pigs, is a major concern.

Ben told me about some of the strict biosecurity measures he has in place to protect his stock. Visitors have to strip down to their underpants and change into boiler suits before going anywhere near the pigs.

Despite the many challenges, he said he and his wife were determined to “build a business for the next 30 years”

Meanwhile, on another Aberdeenshire pig farm not far away

Gregor and his dad, Roderic, are in a pig farming partnership at Logierieve, near Ellon.

They have about 350 sows, again Large White and Landrace crosses.

“We take everything to bacon, finishing all the pigs on site,” Gregor told me.

He and his dad grow their own animal feed too.

Further highlighting the vulnerability of the route to market for Scottish pork producers, the majority of the Bruces’ animals also end up at the abattoir in Brechin.

Roderic has been a pig farmer all his life. Gregor joined his dad in the business in 2020, having previously left home to study physics at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh.

There were also a few jobs in IT and data before the pig farming newbie returned home.

But that was “always the plan,” he told me.

He worries about “critical mass” for the sector in Scotland, given its distance from the main markets, as well as its possible future demise.

But pork prices are holding steady at around £2 per kg, “despite all that’s going on the world,” he said.

Gregor also cited challenges around tax as well as new rules governing the use of nitrogen-based fertilisers.

But it’s worries about African swine fever that are keeping most Scottish pig farmers up at night just now, he said.

Ben and Gregor are both spending part of this year travelling on scholarships.

They are among 24 people from throughout the UK who are trying to gain a better understanding of their study topics from global experts, thanks to bursaries from the Nuffield Farming Scholarship Trust.

Gregor is keen to understand more about pig litter size and what impact it has on gestation and farrowing, as well as management plans to support sow and piglet health.

Conversation