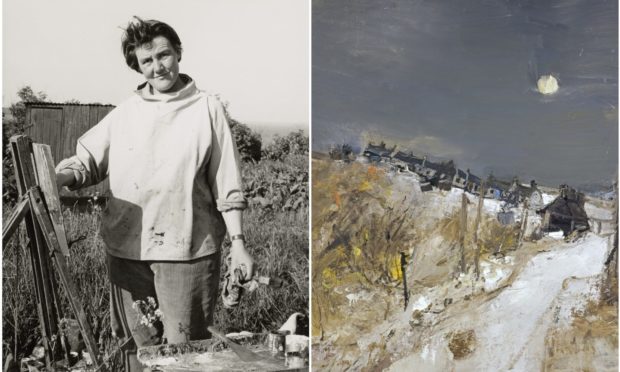

Joan Eardley is adored in Scotland. As May 18 marks the centenary of her birth, Gayle Ritchie looks at the enduring fascination with the shy artist who made Catterline her home.

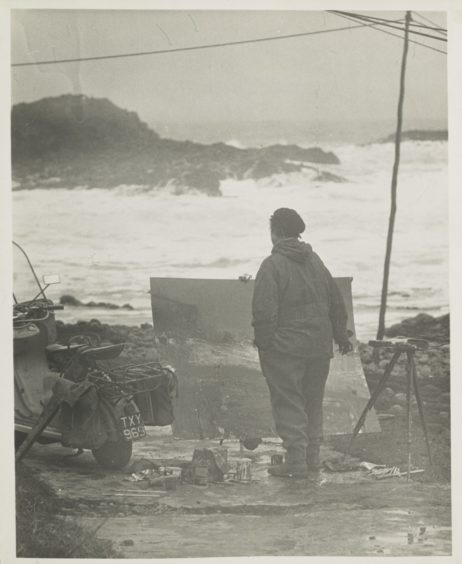

A lone figure stood on the exposed shore, staring out at the raging sea as it whipped cotton wool foam up over jagged rocks.

Dressed in an RAF flying suit and heavy boots, she painted with her easel lashed down against the wind by ropes, boulders and an anchor.

The woman – who frequently ferried her art materials around in an old pram, or zipped down to her favourite spot on the beach on a Lambretta scooter – was, some might argue, a little eccentric.

But here, in the tight-knit fishing community of Catterline, she was respected and accepted as a villager with a strong work ethic and a tough character.

She was, and still is, Catterline’s most famous resident – the artist Joan Eardley.

Drawn to the picturesque Aberdeenshire village in the early 1950s, Eardley didn’t shelter from Catterline’s ferocious storms. She embraced them.

The broiling sea, the gale-force winds, hail, torrential rain, even snowstorms; being at the mercy of the elements – being immersed in her subject – was what inspired her.

In a career that lasted barely 15 years, Eardley was hugely prolific, producing around a thousand paintings and thousands of crayon sketches.

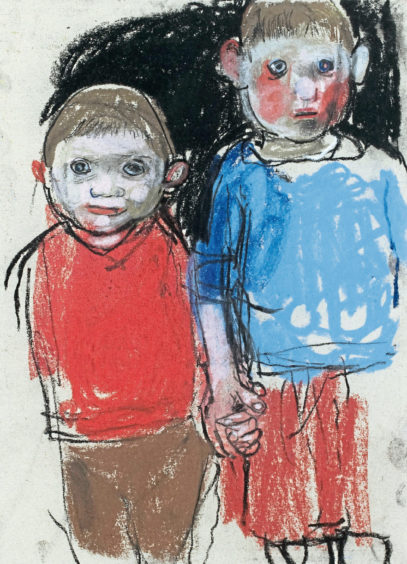

Today her paintings – of bleak seascapes, of fishermen, of fields, beehives and cottages, of slum children, often created using thick, moody brush strokes – fetch five-figure sums at auction.

A difficult start in life

Born a century ago – on May 18 1921 – on a dairy farm in Sussex, Eardley moved to Scotland almost by chance.

In 1929, aged just seven, her father, who had been gassed during the First World War, killed himself.

Her mother took Eardley and her younger sister to London to live with their grandmother and aunt.

But late in 1939, the family moved to the affluent suburb of Bearsden in Glasgow, escaping a London threatened with German bombing raids.

Eardley enrolled at Glasgow School of Art and, finding herself drawn to dilapidation, put down roots among the tenement blocks of the Townhead district, a condemned part of the city, with its clutter of new buildings, half-demolished old ones and obliterated streets, all waiting to be redeveloped.

She had two studios in Townhead where she would often sleep, the first near slums, where she found it easy to get the “slum children to come up”. They initially came to watch her work but soon became a major subject for her art. They would show up and ask to be painted, no doubt hoping for a few pennies to buy sweets.

Scotland’s rugged north-east coast began to seep into her soul

In 1947, Eardley studied for six months at residential art school Hospitalfield in Arbroath.

She took time to draw and paint around Arbroath’s harbour, capturing its working life and sea and sky.

It was then that Scotland’s rugged north-east coast began to seep into her soul.

From 1952 until her death in 1963, Eardley divided her life between Townhead and Catterline.

She first discovered the isolated spot, perched on a cliff facing the North Sea and set around a curved shingle bay backed by a row of cottages, in 1950.

Her friend, Annette Soper, an art teacher from Aberdeen, had invited her to run a solo exhibition at the city’s Gaumont Cinema Gallery.

During her time there, Eardley contracted mumps and her visit to Catterline was part of an extended convalescence.

Within a year, Soper bought the Watch House, a former Customs and Excise look-out on the edge of the village and it became a base from which the two friends would paint.

From 1954 Eardley rented and then bought a cottage at No 1 South Row, which was primitive, to say the least, with no running water or electricity, a bare earth floor and a chemical toilet in a shed outside.

In 1959 she upgraded to No 18 which was in better condition and faced the sea.

The ramshackle cottages, shoreline, cliffs, raging seas, fields and farmland offered endless material. Catterline offered, Eardley once said: “just vast waste and vast seas, vast areas of cliff”.

The second she heard a storm was approaching, she would catch the train to Stonehaven where she would pick up her Lambretta and do the final stage of the journey by scooter.

Painting on hardboard outside (it was tougher and less likely to blow away than flimsy canvas), Eardley employed a plethora of media including artist’s paint and boat paint, with newspaper, sand, seeds and grasses layered into the mix.

Using a palette knife to create texture, she dribbled paint onto the foreground and used the sharp end of her brush to draw into the wet paint.

In her first few years in the village, she painted only cottages; it wasn’t until the mid-50s that she tackled the sea, the beach and the salmon nets.

In the early ‘60s she used collage in many works, including natural materials found in the landscape (seeds, sand flowers and grasses) while in her late tenement paintings she introduced sweet papers, cigarette wrappers and newspaper scraps.

Love letters

As a lesbian at a time when it was not the “done thing” to openly acknowledge one’s sexuality, Eardley was accepted as one of Catterline’s own.

Intimate letters to photographer and musician Audrey Walker emerged in 2013 and her intense love affair with art student Lil Neilson, who she met at Hospitalfield, has been well documented.

Tragically Eardley’s career was cut short by breast cancer and she died in 1963 aged 42.

Her ashes were scattered on the beach at Catterline.

A bit of a mystery

Former resident Ron Stephen met Eardley in 1952 when she first moved to the village.

Eight years old at the time, Ron was initially puzzled by her dress code “as a girl”.

“She was wearing cord trousers, a tweed jacket with leather patches on the elbows and working-style tackety boots,” Ron, a photographer, recalls.

While the people of Catterline were respectful, Ron – who left the village aged 12 – says Eardley would have been a “bit of a mystery” to most.

“The children befriended her after a short time,” he says. “Watching her work was something very new for us. Another draw was the fact she always had a wee bag of sweeties at her easel. She’d share them with us at a time when sweets were under ration.”

Ron and his friends were in awe of this “strange” person who had a love of steamed puddings and was, in their eyes, doing “something exciting”.

They particularly loved watching her paint in storms. “Wind and salt water in her face never bothered her,” says Ron.

“She adapted to the wild conditions by weighing down her easel with an old anchor and shore stones.”

“Wind and salt water in her face never bothered her.”

Ron Stephen

Ron says there are three tangible remaining items in the village by which to remember Eardley: a painting of salmon nets gifted by her mother to Catterline which is held in the Creel Inn; a Historic Environment Scotland memorial plaque on an exterior wall of the Creel Inn; and the Joan Eardley Memorial Quaich, an annual prize for the best art pupil at Catterline Primary School.

A painter’s painter

Many artists find themselves drawn to Catterline, following in Eardley’s footsteps.

Originally from Glasgow, Stuart Buchanan, who describes Eardley as a “painter’s painter”, bought and moved into No 18 – the cottage Eardley had owned and lived in – in 2006.

He had been coming to Catterline since he was a child. “I became aware of Eardley then, meeting artists who knew and worked beside her in Catterline,” he recalls.

“Her paintings would influence any aspiring artist. That almost mythic figure standing on the shore with her canvas weighted down and painting the storm. Heroic and stoic!”

Stuart and his wife Franny began spending more time in Catterline and decided to move there after the birth of their first daughter.

“The owner of No 18, Eardley’s house from 1954 until her death, was retiring in 2006 and had mentioned selling so I literally chapped on the door and asked if we could buy it,” he says. “We shook hands on it there and then.”

As far as his paintings are concerned, Stuart says Eardley is an influence “only in that she was such a stupendously gifted artist”.

“Every artist needs to find their own way and for a long time I avoided making the village a subject but after a while it becomes inevitable,” he says.

“Catterline has a rugged beauty rather than being pretty. It still looks like an Eardley painting on a winter’s day. The storms are frequently epic and dramatic.

“Any artist would respond to this environment, not just the storms and seas and sky but also the rural side, the surrounding farmland, the seasons and rhythms of nature and agriculture.”

Stuart reasons that while Eardley is “beloved” in Scotland, it’s a testament to her enduring popularity that the “main institutions” showcase her work more frequently than others.

Brave and passionate

Montrose-based artist and curator Kim Canale has been a fan of Eardley’s work for more than 30 years.

“We’ve had several exhibitions on Catterline and Eardley at Wall Projects (Kim’s studio) over the years.

“It’s not sentimental in any way, but she was a romantic, and it showed in all her work.”

Kim and Stuart are exhibiting together in August to celebrate Eardley’s work.

“It’s brave and passionate, and way beyond her years; it’s as important and fresh as it was in the 1960s,” muses Kim.

“The fact she was a woman who’s had a major impact on breaking into the mainstream art world is significant. But like all good things, it takes time… and this is Joan Eardley’s time to sing.”

Eardley’s influence

Libby Curtis, head of Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen, says Eardley’s influence continues to be felt by students and artists across Scotland, with successive generations being inspired by her work.

“Eardley’s extraordinary paintings express such a strong sense of place, capturing the wonderful qualities of the north-east and fixing them in our imaginations,” she reflects.

“She is held in such high esteem by the art world and public alike, and we are lucky to have very fine examples of her work in the Aberdeen Art Gallery collection.

“For many it is not possible to think of the north-east without thinking of her, and it is wonderful that the centenary of this hugely significant artist is being celebrated and that her reputation continues to grow.”

Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums Manager Christine Rew describes Eardley as one of the most important artists in 20th Century Scottish art, particularly in the pivotal post-war period.

“Her work represents an extraordinary range and inventiveness, from her sensitive renditions of Townhead’s working class children to the wild landscapes of the North Sea coast,” she says.

“It crosses the boundaries between realism and abstraction and strongly identifies with the places where she chose to live and work.

“It was at the Gaumont Cinema Gallery in Aberdeen that Eardley’s first exhibition was held in 1950, and on this trip she discovered Catterline, where she was to spend so much of her time.”

Aberdeen Archives, Art Gallery and Museums have built up a representative collection of Eardley’s paintings since 1956 when one of her most tender and expressive paintings Brother and Sister (dated 1955) was bought.

“Subsequently, we acquired five more landscape paintings of Catterline including one of our visitors’ favourites Harvest Time, which is currently on display.” says Christine.

The gallery also boasts a large collection of her works on paper, including drawings and sketches, which were gifted by Eardley’s sister Pat Black in 1987.

These are included in an online exhibition at aagm.co.uk to mark the 100th anniversary.

“The drawings illustrate Eardley’s ability to capture busy quayside scenes, working lives, landscapes and children,” adds Christine.

Trailblazer

Eardley’s influence continues to be felt by students and artists across Scotland, with successive generations inspired by her work.

Dr Helen Gorrill, a lecturer in contemporary art practice at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, believes Eardley has never been given the platform she deserves because she’s a woman.

“Her work fetches 0.5 per cent of the value of her contemporary male artists but she’s so well thought of in Scotland,” Helen says.

“The art world is still very masculine. When a woman signs a painting, the value actually goes down – it’s shocking – but back in the day it was even worse.

“At the time she was painting in Catterline, Eardley must’ve been seen as a trailblazer.

“Women were in the house; they weren’t out on the beach challenging the forces.

“Eardley painted in Catterline in storms, literally tying her canvas to rocks. I often wonder what the local women must have thought of her. She was doing such a masculine thing.”

Women were in the house; they weren’t out on the beach challenging the forces.”

Dr Helen Gorrill

Helen is in awe of Eardley’s ability to blend sea and sky together to reflect extreme weather conditions: “She was literally a yachtswoman in a storm – fearless!”

An honest artist

Chenoa Beedie, student director of equality, diversity and inclusion at DJCAD, describes Eardley’s work as an “honest piece of home”.

“Think of the most famous Scottish paintings and there’s a great focus on romanticism, with wild, open, Highland landscapes – as in Landseer’s Monarch of the Glen,” she says.

“In my opinion, it’s a misrepresentation of Scotland because it’s from an aristocratic view, and doesn’t portray the mundane and everyday.

“Sunny glens, deer running around – Eardley doesn’t paint that. Her work is about poor kids playing in slums and the rain and gales of Catterline.

“Some might describe it as bleak but it’s more honest; it’s a piece of home.”

Final year DJCAD contemporary art practice student Tilda Williams-Kelly is another Eardley admirer.

“What she was doing was out there; it was strange for a woman,” she says.

“Her ability to work loosely and choppily is really impressive. She painted in one sitting and to capture the light and environment in one go is really tricky.”

Today, Eardley is celebrated as a great artist because she taps into universal themes – of childhood, of life and nature.

It’s almost 60 years since she died, but here in Scotland, she continues to grow in popularity.

- DJCAD is hosting an online symposium – Joan Eardley: New Perspectives – on June 2 to celebrate the artist’s centenary through the eyes of Scotland’s top art students and special guests. See eventbrite.co.uk for details.

- A new book, Joan Eardley: Land and Sea – A Life in Catterline, reveals fragments of the love story between Eardley and Lil Neilson. The author is Patrick Elliott, chief curator at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art.

- The website, joaneardley.com, was commissioned by the artist’s family to mark the centenary and is a hub of information about events and exhibitions.