It was that sliver of paper, peaking out of the wallet of fraud suspect Roy Allen, that first brought Oregon, USA, into the frame for Aberdeen detectives.

So what did it all mean?

It later became clear that Alison Anders had fled justice in Aberdeen in June 1988 for Abu Dhabi – and then upped sticks once more.

In August 1988, Anders left Abu Dhabi and flew to Singapore and then onwards to Vancouver in Canada.

She then took a Greyhound bus and ended up in Portland, Oregon.

The 30-year-old had travelled across the world and was now alone, with no support and little money.

She had to think fast.

Anders’ first move was to buy a copy of the Oregonian newspaper and scan the ‘wanted’ ads – and there she saw a room to rent.

‘We only knew her as Ann’

That room was being let by hairdresser Carinda Bohus, who has shared her story for this series for the first time.

Now living in Anchorage, Alaska, Ms Bohus told us: “I placed an ad in the paper for the room for rent and Alison answered it.”

On the run, Anders knew she had to keep her wits about her as one false move might lead to her arrest.

The fugitive knew that Ms Bohus might ask for her passport for ID when renting out the room and it had to match the name she gave.

And so Alison introduced herself to Ms Bohus as Ann.

Ms Bohus added: “We didn’t know her as Alison – to us she was always Ann.

“My first impressions – she had a nice accent and she seemed like she would pay the rent. It was a real nice situation.

“She was real nice to get along with and real smart.”

Anders settled in to her new surroundings quickly.

She and Ms Bohus became friends.

They would attend rock concerts together and Anders showed her caring side.

Ms Bohus said: “I was taking a math class at the community college. I’d always been bad at math.

‘She was a very trustable person’

“Alison’s parents were teachers so she tutored me and I got an A in math for the first time in my life. That was real nice of her.”

Ms Bohus took a shine to Anders and got her two jobs in downtown Portland.

One was taking payments at the restaurant that Ms Bohus’s father, Frank, owned, while the other was working at a florist.

That florists was Jacobsen’s – named after Ms Bohus’s auntie, Patricia Jacobsen.

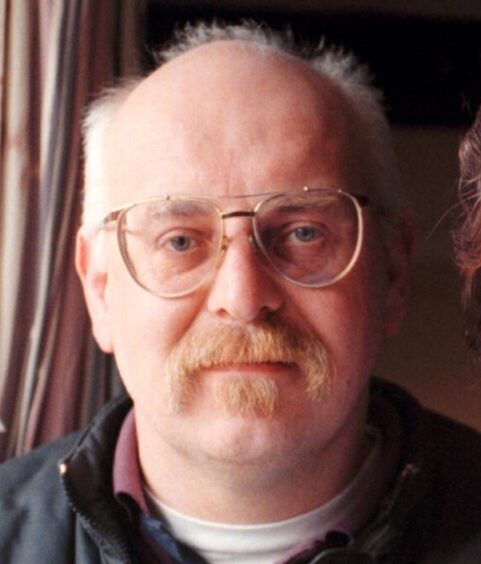

Frank, whose family are of Hungarian heritage, said: “Alison would work in the restaurant on Saturdays and Sundays.

“She was running the cash register. It was a truck-stop restaurant.

“Alison was a very trustable person, as far as we were concerned.”

Anders had arrived in Portland in August 1988 – and had become a regular fixture in the Bohus household within weeks.

Hushed phone calls and a bombshell secret

“She spent Thanksgiving with us that November and often visited us.

“To us, she just behaved like an average girl.”

It was from the florist that Alison Anders had been making secret phone calls to her lover, Roy Allen, back in Aberdeen during her time on the run.

And, when anyone except Roy would pick up, she would say: “It’s Ann calling for Roy.”

By the time autumn 1988 rolled around, the emotional weight of the situation had begun to take its toll on Anders.

She had been out of the UK and away from all that she held dear for around four months, with her future lifeplan – and liberty – up in the air.

Anders had been living a lie for so long – and she could keep it to herself no longer.

The fugitive had formed a strong bond with Ms Bohus – and, with a touch of bravado about her, it was time for Alison Anders to come clean.

Anders trusted Ms Bohus enough with her bombshell secret to explain why a married man from Scotland kept calling.

Ms Bohus said: “She told me what she did (about the attempt to steal £23m from Britoil in Aberdeen). I didn’t believe her.”

After that monumental confession, the stakes got higher.

Anders received a frantic phone call from someone back home to let her know her mugshot had just been put on Crimewatch.

‘I thought she was going to kill me’

Panicking, Anders told Ms Bohus that her face had just been broadcast on a TV show watched by about 14 million people.

Not that Ms Bohus had heard of Crimewatch, living in the USA.

“We understand that this show was like American’s Most Wanted or something,” said Ms Bohus.

She added: “I told my older sister (about Anders featuring on Crimewatch).

“My sister said ‘oh my God, that explains all her cloak-and-dagger phone calls’.

“And then I thought ‘well, if my older sister believes it then perhaps (Alison) wasn’t lying. Maybe she really did try to steal all that money’.

“I started to believe her and I started to get afraid that, if I left knives around, she was going to kill me.”

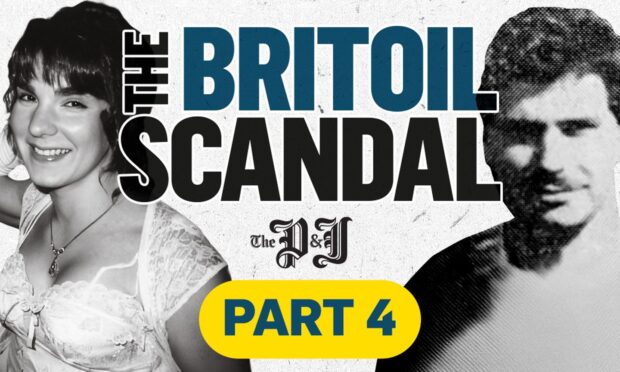

She was a really arrogant individual. She was aloof, as though she was above all this.” DC Moir on Alison Anders

Ms Bohus felt torn between feeling deceived by Anders, even scared of her, and wanting to help her evade capture.

She told us: “I was a hairdresser so Alison wanted to take her hair from black to blonde.”

Perhaps if Anders looked different to her Crimwatch appeal image, she might stay under the radar.

So Ms Bohus helped Anders change her appearance.

But what upset Ms Bohus most was the lie Anders told her about why she first ended up in the US.

Anders had previously told Ms Bohus she emigrated because her parents died – a false story.

‘They’re going to have a phone bugged’

Ms Bohus said: “When Alison told me the real story, I was most mad about her saying that her parents had died because I felt so bad for her and her parents hadn’t died at all.

“Alison told me that she mostly did the fraud for Roy Allen – that she wouldn’t have done it otherwise.

“I told her that I liked the name Alison better than Ann, anyway.

“We talked about the phone calls she was getting from back home.

“I said ‘boy, do you not watch TV? If you did what you say you did, they’re going to have our phone bugged – which they did’.

Ms Bohus added: “I said ‘if you watch (those crime dramas) on TV, you’re going to get caught. It’s going to happen, sooner or later’.”

The FBI starts snooping

Detective Constable Hamish Moir, who was then based at Queen Street Station in Aberdeen, said: “We had found a phone number on a sliver of paper in Roy Allen’s wallet.

“It was a US number, for a flower shop in Oregon.

“Once we had figured out where the phone number connected, we got the FBI involved.

“They went and carried out surveillance on the place – and saw Anders.

“The FBI got into her apartment and got hold of her passport, which had the name Ann Glenda Kellick.”

At last – a smoking gun.

Word filtered back to Aberdeen that their FBI counterparts had not only verified The Day of the Jackal passport-fraud story – but also tracked down Alison Anders herself.

FBI special agents found Ms Bohus and gathered information that would help them finally take down Alison Anders.

Ms Bohus said: “Scotland Yard got me at my community college.

“The story was so crazy that I thought they were kidding and that it was the drama department playing a prank.

‘We’ll get her at the bus stop’

“When I saw they were following me home, I knew they were serious.

“By then, Alison had already moved into somebody else’s place.”

It was at that point that the FBI struck a deal with the Bohus family, who were concerned business would suffer if people saw Anders arrested there.

We can reveal that special agents agreed that, in exchange for information from the Bohus family, they would arrest Anders elsewhere.

Ms Bohus said: “I said ‘please, don’t get her at my aunt’s shop because my aunt has a very respectable shop’.

“So I said ‘Alison catches the bus’.

“The FBI said ‘for you, and your aunt, we’re going to get her at the bus stop when she gets off work. Don’t call her’.

“They did that for me. They had also met my aunt and they wanted to be nice to her too.”

Everything was in place.

The FBI was going to finally take Alison Anders down.

Time on the run comes to an end

It was May 18 1989 – almost 11 months since the failed fraud and nine months since Anders had arrived in the US.

At 2.40pm, Anders finished her shift at the florist and made her way to the bus stop nearby.

Just like a Hollywood movie, FBI special agent James Russell and his colleagues moved in and held Anders at gunpoint while she fiddled in her purse for her bus fare.

She was arrested – and police found in her possession a passport bearing the name Ann Killick.

Mr Bohus, who had given Anders a job at the truck-stop restaurant, said he had no idea about Anders’ criminality.

And so he was shocked by the arrest.

He told us: “Jodie – my wife’s niece – was working at the florist’s at the time and the FBI arrested Alison outside.

“Jodie said ‘we couldn’t believe it’.”

“The FBI told Jodie nothing.

“We found out the next day what had happened by reading the paper.

“When I read it, I just about fainted. We didn’t know what to make of it.”

Those familiar with the case claim Anders was relieved her life on the run was over.

She was missing her lover, Roy Allen, and was tired of the constant lies.

Anders was close with a Portland pastry chef named Brad Smith and there were media reports they were a couple.

After her arrest, Mr Smith told the media he and Anders had been planning to get married and he only discovered Anders’ real identity when she called him from custody, asking him to bring some of her belongings.

‘She wanted to avoid a US jail cell’

Mr Smith said that, despite that, he would be willing to give things another go.

Ms Bohus said: “Brad was gay. They were just friends.

“Maybe they were going to get married (for visa reasons), but he was gay.”

Anders appeared before US magistrate George Juba and waived her right to an extradition hearing.

DC Moir said: “Most people did, because all they would be doing is prolonging their time in an American jail.”

A media frenzy

Anders was flown back to London and was met by DI Bryan Bryce and DC Ann Allan, of Grampian Police, at Heathrow Airport.

Her arrival back on Scottish soil generated a media frenzy.

Every newspaper around published reports of the £23m oil money plot formed over a game of bridge, with photographers battling for the best place to get a photo of the returning fugitive.

The Sun described her as a “flame-haired yuppie” as she was photographed wearing a shoulder-padded coat, such was the style at the time.

DC Moir told us: “When Alison came back, I read the warrant to her.

“She was a really arrogant individual. She was aloof, as though she was above all this.”

On June 12 1989 – three weeks after her dramatic FBI arrest – Anders appeared at Aberdeen Sheriff Court.

It took another 10 weeks for prosecutors to get to trial.

Anders and Allen stood trial at the High Court in Aberdeen on August 28 1989, almost three months after she returned from the US.

Representing the Crown was Roderick Macdonald KC, who later became a High Court judge with the title, Lord Uist.

Jack Davidson KC defended Anders.

Britoil scandal ‘a breathtaking scheme with a fatal flaw’

Both of them spoke for this series.

Mr Davidson said: “My overall impression was that it was quite a breathtaking scheme which, but for one fatal flaw, let Anders and Allen down and put the authorities on their tracks.

“It was quite a chain of events that led to the court case.”

He added: “Alison wasn’t easy to warm to. She seemed pretty stoical.

“I never got the impression she was particularly worried about having her crimes aired in public.

“This was all new to her and these were serious charges hanging over her.

“You wouldn’t expect her to be providing entertainment in the course of conversation, but she was fairly pleasant.”

Lord Uist told us: “It was obvious it was going to be a high-profile case, but that never influences how you approach the case.

“It was at Aberdeen High Court.

“Back then, the High Court sat in a room that was colloquially known as The Turkish Brothel below the library in the Sheriff Court.

“It got its name because of the garish, purplish wallpaper.

“It’s not spacious but it’s not tiny. You always get the pigeons coming down in the afternoon and settling outside the window.”

‘A pretty compelling picture with no answer’

And, while there were elements of drama in the courtroom, the trial itself was a damp squib.

Anders and Allen were accused of forming a fraudulent scheme to defraud Britoil of £23,331,996.

The indictment alleged that, between June 28 and 29 1988 – the year before the trial – Anders and Allen acted with others and tried to transfer money from a Britoil account to an account in a Geneva bank, using a forged international payment application.

Anders was also accused of obtaining a false British passport in the name of Ann Glenda Killick.

On Day one, Anders wanted to plead guilty to the charges against her.

Mr Davidson said: “It was a classic circumstantial case – a little evidence from different sources, which came together to form a pretty compelling picture to which there was really no answer.

“You can live in fantasy land and say ‘you never know with a jury’ – but she was done out of the park and she accepted it pretty readily.

“It was the biggest attempted fraud in Scottish legal history.

“She must have realised there’s not terribly much meaningful you can say to minimise that, other than she has held her hands up and cooperated.

The game is well and truly up

“Maybe she thought ‘the game is well and truly up, I might as well get this over and done with, serve my time and get on with the rest of my life’.

“She was quite intelligent.

“She was switched on and probably realistic in terms of what she was going to expect in court.”

Lord Uist said: “Alison Anders had written some annotation on the money transfer application on the day she went into the bank to try to get the £23m.

“She could well have succeeded had she not written that on the cheque. That was her downfall.”

But there was a problem.

While Anders was willing to admit her guilt, her co-accused Roy Allen was not.

This was despite there being evidence of him forging signatures on the passport and of not telling police he knew where Anders was for months while speaking to her on the phone.

Pitting one accused against the other

Mr Davidson said: “I don’t think Anders was terribly impressed by the fact that her co-accused was going to trial.”

That meant Lord Uist, for the Crown, had a good reason to not accept her plea.

He added: “Roy Allen had not pleaded guilty.

“In order to lead the evidence, for it to make sense to the jury – I would be required to lead the evidence against them both, because his conviction would hang on hers.

“It would be possible to do it without her there but, from the jury’s point of view, it would look very odd.

“It would be like watching a play without a key actor.”

Using a dead girl’s passport to flee

The court heard two days of evidence that established Anders had come up with the plan.

The jury was also told Anders obtained a false passport using Ann Killick’s identity, booked a flight abroad and tried to transfer the £23m.

An image began to emerge in the minds of the jurors of the worldwide adventure that Anders had been on in the previous year or so – all under the name of a dead schoolgirl.

Then, on day three, the prosecution accepted Anders’ guilty plea, leaving Roy Allen as the only person on trial.

Anders gave evidence for the Crown – as did Roy’s estranged wife, now Megan Nance.

Mrs Nance told the court the first she knew about the fraud was when she saw it on TV news.

She told the court: “I rang Roy, who was in Abu Dhabi, and said ‘Guess what, your bridge partner has tried to rip off Britoil for £23m.”

Then, when he returned to Aberdeen, Mrs Nance accused him of having an affair with Anders.

Claims of threats to his kids were false

According to Mrs Nance, Allen denied the affair and said he was only involved with the fraud because he was set to get £5m from it.

She told the court Allen moved out of the property six months after the fraud, in December 1988.

Allen’s defence team tried to argue he had been pressured into participating in the fraud by people threatening his children.

DC Moir gave evidence to deny this and the judge, Lord Morton, threw out that defence.

After the trial, DC Moir told us: “After we matched his handwriting to the forged passport, Allen said ‘I want to speak to you in prison – at Craiginches’.

“He admitted limited involvement and said he had been coerced by people and they had threatened his family.

“But there were no specifics. It was just bull***. The game was up for him.”

The trial ended after five days and the jury retired for the weekend.

A quick verdict from the jury

When they came back on the following Monday, they took just 44 minutes to deliberate and return a guilty verdict for Roy Allen.

Mr Davidson said: “Even though the weekend intervened, 44 minutes is pretty rapid for a jury’s verdict, particularly given the scale of the case.

“I guess with the judge withdrawing coercion from consideration, that was more or less the kiss of death for the co-accused defence.

“We used to think – juries would not come back within 15 minutes because they have to make it seem respectful.”

Lord Uist added: “There were no gasps or anything in court. People thought it was a foregone conclusion.”

‘They were up to their necks’

Lord Morton jailed Anders and Allen for five years, though Anders’ sentence was later reduced to four years on appeal.

Mr Davidson said: “The two of them were in it up to their necks.

“She was very much a central part of the whole exercise.

“If she had been given seven years it would have been hard to say ‘we must appeal that because it’s too much’.

“It was a fairly bare-faced challenge to the banking system with overtones of foreign parties and suggestions of international crime links.

“Five years is still an appreciable term, in the grand scheme of things. It’s a lot more than a slap on the wrist.”

‘This was not Bonnie and Clyde’

Lord Uist added: “There was no sympathy at all for them.

“There was nothing romantic about it in the eyes of the public. It was straightforward greed.

“The accused were regarded as selfish people who were out to get money.

“They were not painted as a Bonnie and Clyde couple.”

Though the Crown had secured two important convictions, the case was far from over.

For, during the trial, one name kept popping up – Hajdin Sejdija.

It was a name that would once again pique the interest of Aberdeen detectives on a quest to crack the case.

- The P&J made several attempts to contact Alison Anders over a period of several months and she did not return our messages.

COMING TOMORROW IN PART FIVE: With two behind bars, detectives begin a dash around Europe in search of a high-powered businessman they marked as the £23m fraud’s mastermind.