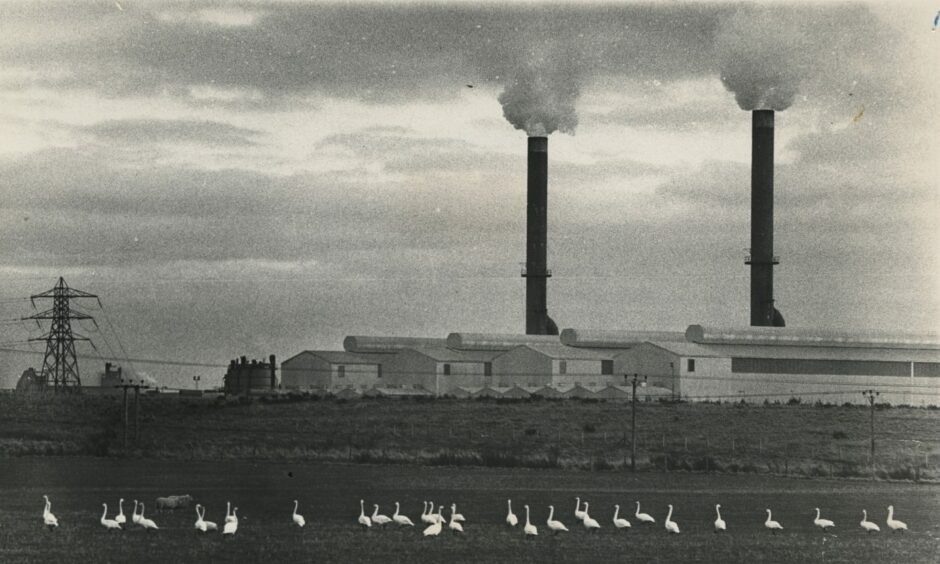

I always liked the fact that an Alginate seaweed factory was down on the machair in the village I grew up in on South Uist. It provided employment, with the shift work particularly useful for crofters who could tend to their cattle and sheep and crops, in between lighting the furnace and burning kelp to ashes.

The best thing was that when you went down there on a cold day you could warm yourself by the furnace and listen or blether away to the workers, in Gaelic. It remains as the best proof I know that retaining an indigenous language and culture and working in an industrial setting need not be enemies.

The Industrial Revolution, and its factories, brought many benefits even if it destroyed many things in its path. Anyone who has read E.P. Thompson’s majestic work The Making of the English Working Class will know of the human damage done in terrible factory conditions in the emerging cities, but will also know of the cultural destruction of the countryside in its path.

As demand for factory workers grew – whether in Glasgow or Birmingham or Dundee or Sheffield – hundreds of thousands of people left the country villages to make their way into the urban slums. They gained some wages and lost their little plots of ground where they might have a cow and a pig and a goat. And fresh air. They lost the country stillness, replaced by factory noise.

Rural poor took songs, music and stories with them

When roads improved and the motor car came, those who could afford it moved out to these area of England’s green and pleasant land while the working classes built their new Jerusalem amongst those dark Satanic mills. Nowadays those patches where the rural poor milked their solitary cow and killed their only pig are valuable property portfolios in an escalating ‘rural housing market’.

It’s well recognized that the rural poor didn’t lose everything immediately. They took with them their religion (whether Methodism in England or Irish Catholicism in Scotland) and their songs and music and stories and mythologies. Some of the greatest songs we have in urban settings are mere transportations from Donegal or Barra or the Howe of Auchterless.

Some argued you didn’t need Gaelic

The areas covered by the Press and Journal are no exception to this pattern. Inverness, for example, has grown and grown, like Pinocchio’s nose, over the past two hundred years or so, drawing thousands in from the surrounding area.

When I first lived there in the 1970s I knew a number of people who were native Gaelic speakers from the town and its surrounding area – in other words, indigenous local native speakers and not just folk who’d moved into the area from Skye or Lewis or wherever. All you had to do was to go down to the weekly mart and you were bound to meet some country farmer who either spoke native Invernessshire Gaelic or whose parents and grandparents had.

For a while there were those who argued that progress and Gàidhlig had nothing to do with each other. That the language was something that kept you back and would – should – go the way of the penny-farthing. You didn’t need Gàidhlig in a vibrant town like Inverness which now boasted concrete offices and roundabouts and even a Wimpy’s. Egg-and-chips for 20 pence!

Paving the way for community co-operatives

But it also had the late and much-lamented HIDB, which did so much to develop the area. Granted, they made their mistakes and often mistook large for good, but who could turn down an aluminium smelter in Easter Ross with the thousands of job it brought or oil developments at Nigg or elsewhere?

Though they were adventurous too, in those glorious pre-Thatcher days when fiscal risk was permitted. Under the wise guidance of Bob Storey they paved the way for community co-operatives. A pity the bulb-growing scheme didn’t flourish, though I always admired their support for the perfume business in Barra (an enterprise before its time) and the spectacle-frame-making factory on the same island which employed 12 women at one time.

Alginate Industries in my own village employed about 20 or so, processing seaweed which ultimately served to stabilise meringues and ice-cream, and emulsify cosmetic and medical products. Who knew that seaweed from South Uist, cut and processed by Gaelic workers, glued Marilyn Monroe’s lipstick together?

Oh, and the manager of the factory at that time of my childhood was Lt Col Colonel Cameron who celebrated his 100th birthday a few months ago in Auchterarder Perthshire where he lives. Co latha breith sona dhuibh. Happy Birthday, Sir, and thanks for everything.

Angus Peter Campbell is an award-winning writer and actor from South Uist