Bliss it was to be among the spectators at the Rugby World Cup final in South Africa 25 years ago when sport became a redemptive force for the Rainbow Nation.

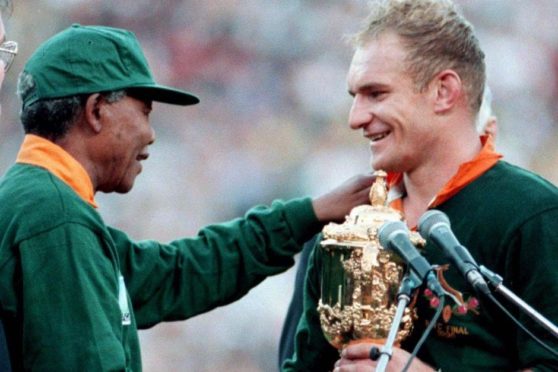

The memories of that resplendent occasion on June 24, 1995 are forever etched in history: the sight of Nelson Mandela and Springbok captain Francois Pienaar holding the trophy together, the president wearing the No 6 jersey of his team’s captain and the crowd of all races joining en masse in a spine-tingling rendition of “Shosholoza”.

Yet, while even the neutrals left Ellis Park in Johannesburg with a beaming smile and a spring in their step, plans were being devised and fine-tuned off the pitch for rugby union to be transformed from its old amateur status into a fully professional sport.

A quarter of a century later, the impact of that development has been a decidedly mixed blessing. Yes, there is no denying the best players deserve to be rewarded for their talent and it was a nonsense that some of Scotland’s finest found themselves in situations where they were winning a Grand Slam on Saturday, then fixing the plumbing in a public toilet or doing a night shift with the police the following Monday.

But, while these issues needed to be tackled, and the advent of professionalism has yielded a range of positive factors such as the creation of European tournaments, the advancement of TV technology to help match officials and the expansion of women’s rugby, it has also been nothing short of catastrophic for clubs – and nowhere has this been more apparent than in Scotland.

At the outset of the brave new pay-for-play era, there was an opportunity for grassroots organisations to seize the initiative and one or two responded to the challenge. Melrose were a driving force in the Borders and Glasgow Hawks orchestrated bold proposals for a club structure across their homeland, which would be based around the cities.

At the outset, Hawks even recruited a string of high-profile players and were sufficiently powerful to beat Toulouse in one friendly and draw with Newcastle Falcons in another. At the time, I contrasted their refreshing vision with the desperate ostrich-like manouevres of the panjandrums at Murrayfield, but ultimately, the SRU won the day and their stewardship has gradually, inexorably allowed the clubs to wither on the vine.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic cast a blight over sport, there were mutterings of discontent about the behaviour of the governing body in Edinburgh and I’m expecting these grievances to increase in the months ahead, not least because rugby, as a whole, is grappling with numerous concerns and the interests of clubs seem low on the list of priorities for those attempting to navigate a path out of lockdown.

In global terms, the Six Nations badly needs a shake-up to boost the prospects of second-tier countries; and the Southern Hemisphere superpowers have to provide much greater backing to the likes of Fiji, Tonga and Samoa, whose decline at last year’s World Cup exposed the vast financial gulf between the haves and have-nots.

On the domestic stage, it’s time we heard fewer platitudes from the SRU and more signs that they realise the scale of the problems which are afflicting so many clubs. Let’s just list a few: given the demands of social distancing and the new restrictions on bus, rail and air travel, how are many organisations, particularly those in the Highlands and Islands, even going to be able to fulfil fixtures, if and when normal service resumes?

How will the likes of Highland and Aberdeen Grammar prepare for the resumption of competitive league action when, as the latter’s director of rugby Gordon Thompson told me last week: “We are in a state of suspended animation”?

And, despite the financial support being offered by the SRU, when will we see the creation of a championship structure which is actively promoted by the powers-that-be, rather than sidelined by the latest pieces of PR fluff from Glasgow and Edinburgh?

In the current unprecedented circumstances, everything should be up for discussion. As somebody who used to dread the SRU’s annual agm, I sympathise with those who have grown accustomed to the banal blethering of the blazerati.

But the next meeting, scheduled for August 15, is a chance for clubs to demonstrate their renewed commitment to tackling the administration head-on. There has been plenty of criticism of SRU chief executive, Mark Dodson, for his stewardship of the game and the way he fell out with the international authorities at the World Cup.

However, I’m more concerned about his apparent lack of interest in the fate of the very organisations who keep the game alive in Scotland. At the moment, everything is being flung into the two professional teams, but the clubs have to point out the folly of that policy. Will they actually offer a united front in arguing their case?

They couldn’t manage it 25 years ago when professionalism arrived in a splurge of new contracts and pound signs. But, no matter how belated their response, it could well be the last chance to remind the salaried staff at Murrayfield that the clubs are the SRU.