Politics are never far from the sporting agenda these days.

Whether it’s discussion about Ukraine’s footballers becoming everybody’s favourite other team, the disregard for human rights in Qatar, which will stage the World Cup later this year, or wealthy golfers making excuses for joining the new Saudi tour, there is a clear link between disreputable governments and leading names in football, golf and other pursuits.

Yet, while some millennials might imagine this to be a new development, it’s as old as time immemorial and, 45 years ago this week, the Scotland team flew into the eye of a storm when they travelled to South America for a summer series of matches against Chile, Argentina and Brazil.

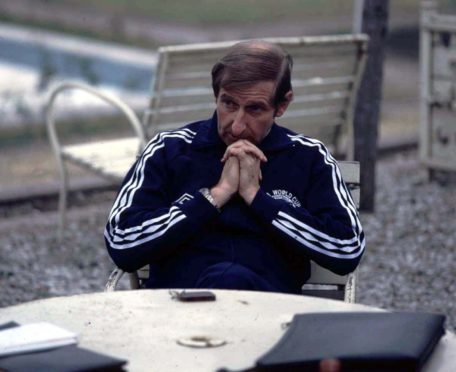

Just a few days earlier, the effervescent Ally MacLeod, who had left Aberdeen to take charge of the national side, had steered the SFA’s finest to an unforgettable 2-1 win against England at Wembley. But if that was a joyful occasion, there was nothing to cheer about the trip to Santiago which opened the eyes of the squad to the worst excesses of the Pinochet regime.

Even in advance, controversy reined. Months before the Scots had left the tarmac in Glasgow, Amnesty International had sent the players literature which highlighted a catalogue of abuse against ordinary Chileans. Allied to this was the systematic murder of thousands of dissidents as part of the dismantling of democracy and the installation of a military dictatorship.

This information was posted to the players individually and one of them later told me: “We should have been mature enough to reach a collective decision, namely that it was obscene to even consider participating in any sporting event in a stadium where thousands of human beings had been murdered.

“Predictably, however, as mostly young footballers, we stuck our heads in the sand, motivated by the thought that if we refused the chance to play for our country, there were plenty of others who would happily take our places.”

Hence the arrival of MacLeod’s party in the capital on June 12. The manager, himself, had expressed some concerns, but these were swatted away by the governing body at Park Gardens with the attitude: “Stick to football”. All that mattered was getting attuned to the conditions they would face in the World Cup in Argentina 12 months later (for which the Scots still had to qualify).

None of which adequately prepared the team members for their experience of living in a war zone for the next few days. As goalkeeper Alan Rough recalled: “Heaven knows why the SFA agreed to a game in these circumstances. It was horrendous. There was a 10pm curfew across the city and we could hear the regular sound of gunfire from our hotel rooms.

“The military were everywhere and the locals working in our hotel told us how people had been rounded up, bundled into the back of lorries, driven to sports stadiums throughout Santiago and summarily executed without trial – and there we were, a daft bunch of laddies waiting to play a trivial football match.

“On the afternoon of the so-called ‘friendly’, we reached the ground at 5pm and the atmosphere was stomach-churning. Even the normally garrulous, high-spirited MacLeod seemed stunned by what we all saw.

“As I walked through the arena, I spotted bullet holes all along a wall which the Chilean authorities had tried – and failed – to conceal with plaster. For the first time in my life, I was forced to confront the question: ‘Where do you draw the line?’ We won the match 4-2 (with a brace for Lou Macari and others from Kenny Dalglish and Asa Hartford), but I never felt less like celebrating a victory in my career and I went straight to bed that night”.

His words reflect what many of us often forget: that these players are normal young men and women with the same anxieties and apprehensions lurking beneath the surface as the rest of us. It was the same with the Scottish sprinter Allan Wells, who was sent photographs of dead children by politicians who wanted Britain to boycott the 1980 Moscow Olympics.

When I spoke to the Scot who surged to golden glory in the 100m final, it was clear the incidents had left an enduring mark. He said: “We received maybe half-a-dozen letters from 10 Downing Street trying to put us off. I opened one of them. There was a picture with a letter saying this is what the Russians are doing. It showed a dead Afghan girl with a doll.

‘That picture haunted me’

“I can still see the picture even now as if it were yesterday. It made me feel very angry that we were being pressured to this extent. I think, deep down, that the government wanted us to go, but also wished to please the Americans [who withdrew their athletes from the Games].

“My first thought was: ‘What’s going to happen if I don’t go?’ A Russian soldier isn’t going to say: ‘Oh, Allan Wells isn’t coming. I’m not going to shoot somebody’. And the government kept signing trade deals with the Russians.”

We can expect plenty of reports about iniquities in Qatar in the coming months. As usual, sportspeople will be pawns on the political chess board.