A century ago (June 5 1921), a man died on a bleak Tibetan plateau. He was on the First, 1921, Expedition aiming to conquer Mount Everest; indeed he was the very first “martyr” to Chomolungma (to give the mountain its proper name).

That man was, at that time, recognised as the greatest Himalayan mountaineer of his day, and after his death two memorials in Tibet were raised to him and two mountains, one in Sikkim and one in Tibet, named after him.

Lauded by all mountaineers and explorers of the Himalaya in his lifetime – and for many years afterwards – that man is today almost forgotten.

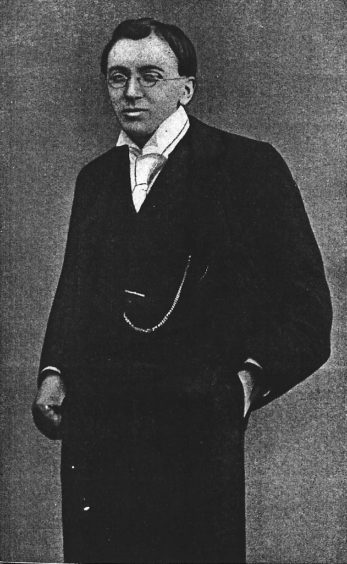

Who was he? He was Alexander Kellas, and he was born in Aberdeen in 1868.

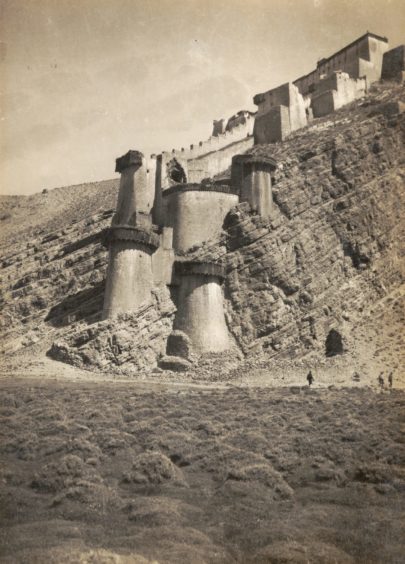

What led Kellas from his birthplace at the Aberdeen harbourside to his death on the windswept plains below Kampa Dzong half a century later?

Early life

Kellas was born in 1868 of a middle-class family. His father was the head of the Aberdeen Mercantile Marine Board, a quango running the many affairs of the bustling city port.

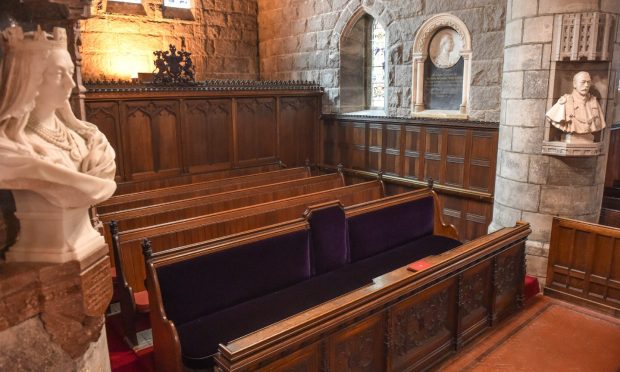

The mansion on Regent Quay where Alex was born housed both his father’s offices and the family dwelling house. But when he was 10, the Kellas family moved to Carden Place in the west end, partly to escape the increasingly crowded and slum-ridden area of dockland, and partly so Alex could now attend the nearby Grammar School, which had moved in 1863 into its new premises.

He appears to have been inspired by the school’s most famous former pupil, Lord Byron, and the latter remains the only poet Kellas ever quoted.

Kellas had a troubled time at school and for reasons we do not understand interrupted his studies for a couple of years; possibly a harbinger of the mental issues which troubled him later.

However, he had an escape, in that his mother’s side of the family, the Mitchells, were prosperous farmers on Deeside and tenants of a farm called Sluivanniche in Ballater; the house is still in the Mitchell family possession.

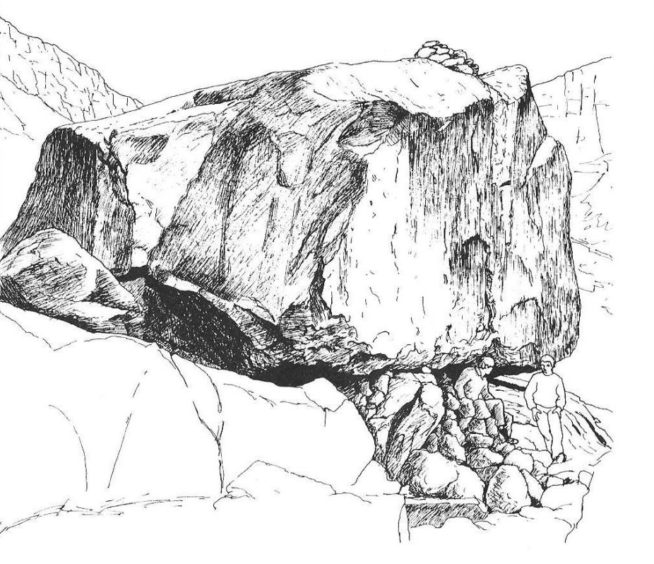

Here, Kellas was to spend much time exploring the Cairngorm Mountains. Starting with day trips to neaby Lochnagar, he soon branched out and went on long walks into the deeper Cairngorms where his favourite overnight stop was the Shelter Stone below Ben Macdui.

His enormous stamina was already evident in the trip he made when 17 with his brother Henry, who was 15, when they walked from Sluivanniche to the Shelter Stone, a distance of 35 miles, in 12 hours, over-nighted there, then climbed Ben Macdui, and on the same day walked back to Ballater.

Successful career

Kellas returned to study first at Herriot-Watt University in Edinburgh and then at University College London (UCL) where he took a degree in chemistry in 1892. Here he was head hunted by the most notable research chemist of the day, the Glasgwegian William Ramsay. Kellas worked with him on the programme which led to the discovery and classification of the inert gases (neon, argon, etc) and which earned Ramsay the Nobel Prize in 1904. Kellas was mentioned generously in Ramsay’s acceptance speech.

Kellas continued to mountaineeer, both in Scotland and in Europe, visiting Norway and making forays to the Alps. But it should be stressed that by the time he was almost 40, Kellas had done nothing that would even earn him even a footnote in the history of mountaineering. In the space of a few years however, he would be seen as the leading Himalyan mountaineer of his day.

What changed? Well, 40 and a batchelor, Kellas must have been wondering where life went from here. He had moved to a mundane teaching job at Middlesex Hospital in London and his exciting days of working with Ramsay were over.

His father died, leaving him a modest sum of money that could be put to use. So where did Kellas go? He went, suddenly, to the Indian Himalaya. And he revisited the Himalya almost every year until war broke out in 1914.

Before that date Kellas had climbed several virgin peaks in Sikkim above 20,000ft and had spent more time at that altitude than any man alive. These ascents of Langpo Peak, Chomiumo, Kangchenjhau and Pauhunri defeated several strong mountaineers who followed Kellas.

Unknown achievement

One of the many tragedies of Kellas’ life is that Pauhunri, at 23,375ft, which he climbed in 1911, was the highest summit till then attained by man, and remained so for 20 years. However, erroneous measurements gave this honour to the much easier peak of Trisul, which had been climbed by Tom Longstaff in 1907. Kellas himself was ignorant of his achievement.

Alexander Kellas climbed Pauhunri in 1911.Over many years (interrupted by the war) Kellas explored the approaches both to Mount Everest and to Kangchenjunga. His knowledge made him a natural choice for inclusion in the first Mount Everest Expedition of 1921 and, had he not been in his 50s, he would in all likelihood have been its leader.

Though another issue might have been that Kellas had a mental breakdown in 1919, and resigned from his teaching post, before leaving for India after a period of recuperation at home in Aberdeen. Here, supported by his family and his brother Henry, Kellas took private consultations with professor Ashley Mackintosh, manager of the Aberdeen Asylum. Mackintosh’s prescription of rest, massage and good food appears to have helped Kellas regain a tolerable mental equilibrium.

Kellas had visited Kamet in the Garhwal on various occasions and, when he returned to India in 1920 with Morshead, reached over 22,998ft and had broken the back of the mountain. They were poised for the summit when a porters’ rebellion ended the attempt.

On Kamet, Kellas, by now was the world’s leading expert on high-altitude physiology, carried out further experiments relating to the use of oxygen at altitude, studies which had occupied him for many years. Based on his studies, Kellas predicted that Everest could be climbed by a fit and strong person without oxygen, and this was confirmed when Messner and Habler achieved this feat in 1978.

Tragedy strikes

He died at Kampa Dzong in Tibet, from a combination of dysenteric illness brought about by unhygienic food, and the effects of his strenuous mountaineering activities in Sikkim before he joined the 1921 Everest Expedition.

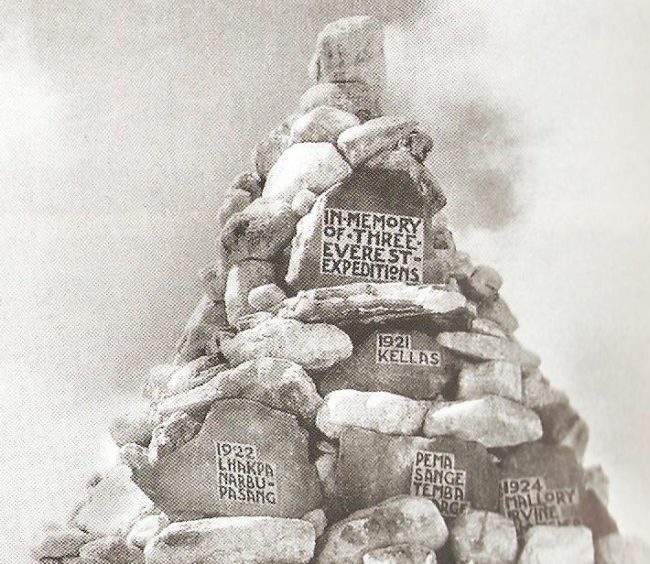

There was a memorial erected at his grave, and later another at the Rongbuk Glacier in 1924, where Kellas was commemorated alongside the duo of Mallory and Irvine (and several sherpas) who had lost their lives on the mountain.

Kellas Rock peak near Everest was named after him, as was Kellas Peak in Sikkim – which is still unclimbed.

Another tragedy for Kellas was that he died the day before the expedition actually first saw Mount Everest, which occurred shortly after the party left his graveside.

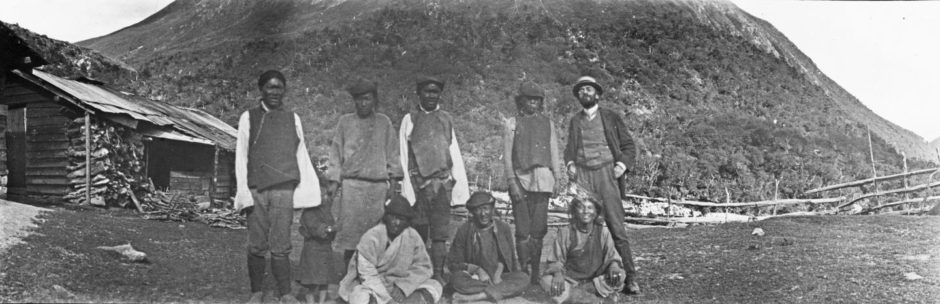

The official account of the 1921 Expedition, written by its leader Charles Howard-Bury, included the team photograph. Yet another irony, it was taken after Kellas had died, and he is The Man Not In the Photograph.

George Mallory, whose name is synonymous with Everest, was a great admirer of Kellas, both as a mountaineer and as a person. When Mallory met him in 1921 he said: “Kellas I love already. He is altogether Scotch and uncouth in his speech, altogether uncouth. He is an absolutely devoted and disinterested person.”

And later on returning home, Mallory paid further tribute to Kellas on a lecture tour when he spoke in Aberdeen at a meeting where he was recorded by the then Aberdeen Journal (7.2.1922), as saying: “In (Kellas) we lost not only a delightful and helpful companion, but a very experienced mountaineer whose services could not be replaced. (applause).” It was Mallory who insisted that the two Himalayan mountains named after Kellas were so.

Denied a sight of Chomolungma, denied the world mountain summit altitude record he had unknowingly gained, Kellas has also been denied due recognition as an explorer, mountaineer and high-altitude physiological pioneer. Partly because he was an awkward provincial, ungainly and prone to mental heath problems, and thus he did not fit the image of “hero” in the way Mallory did.

Further, again unlike Mallory, he was no self-publicist, contributing only a few articles to academic journals, and he kept no diary, wrote few letters.

Hopefully Alexander Kellas’ massive contribution to the story of Himalayan exploration and mountaineering will now be recognised a century from his death.

Ian R Mitchell, an Aberdonian, has co-authored a full biography of Alexander Kellas,

Prelude to Everest. Alexander Kellas, Himalayan Mountaineer, by Ian R Mitchell and George W Rodway, is published by Luath Press.