It was when writing last week’s column on Broadmoor and researching its most infamous inmates past and present that the idea for this column came to my mind.

The Whitechapel murders in London. Committed, of course, by Jack the Ripper. Probably one of, if not the, most famous unsolved murders of all time.

Jack the Ripper was a “person”.

No no, don’t worry, I haven’t gone all woke or gender neutral and am scared to call him a man. Far from it. I called him a “person” because some actually believe that Jack the Ripper was a woman – called Jill the Ripper.

One of the female suspects is Mary Pearcey, who killed her lover’s wife with a carving knife… in a very similar manner to that of the Ripper.

But as to Jack being Jill, it’s not a wildly popular-held belief.

So, back to the facts. “JTR” was a serial killer who in 1888 murdered at least five women in the London area of Whitechapel.

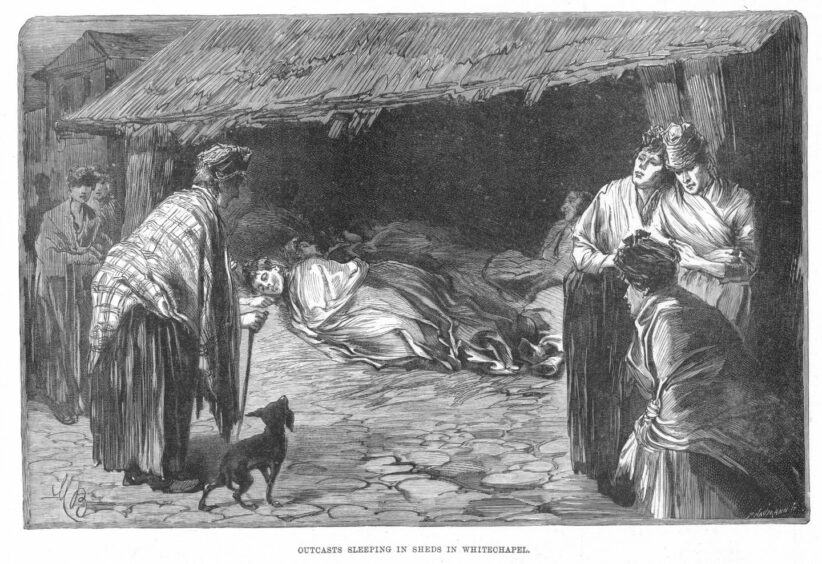

Overcrowded with immigrants, filthy, crime-ridden and poor, Whitechapel is said to have had more than 60 brothels and over 1,000 prostitutes working on the streets. And some of these were to be his victims.

Jack murdered at least five prostitutes, but because he was never caught it is impossible to know the exact number of victims. There were also copycat killings around the same time which may or may not have been carried out by Jack.

Like his identity, we’ll probably never know how many he – or she – killed.

The killings were brutal. The victim’s throats slashed, and then the removal of their internal organs. This apparently was done so expertly that it is believed by many that Jack must have had surgical knowledge. Or was possibly even a butcher or slaughterman.

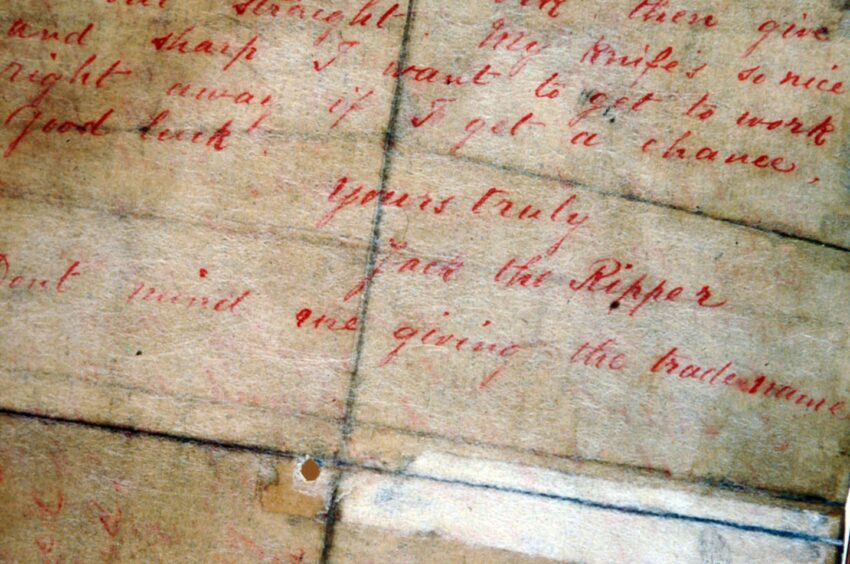

A letter was sent to the press, a “dear boss” letter, taunting the police that they couldn’t catch him. It was signed off: “Good luck. Yours truly, Jack the Ripper.”

It is now widely accepted that this letter was a fake, and actually written by a journalist. In fact, decades later, a journalist apparently confessed that he had written the letter, in order to boost sales of his paper.

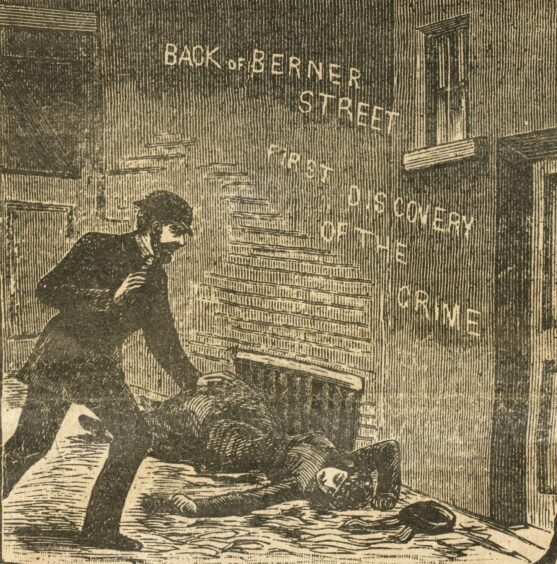

The killings understandably shocked the entire city of London and actually had a huge impact on society as a whole. The police, who of course had no modern forensics at their disposal back then, were really up against it.

That said, they did not help themselves by refusing to share information with journalists, who as we know today help to spread the word and ask people to come forward if they have any information to give. Morale was low among the police who were investigating, squabbles took place and even resignations.

It was a near impossible task. No modern forensics, little help from those who lived in the crime-ridden area, which of course was a warren of tiny passageways and alleyways that were mostly not lit at night. The police did, though, interview, investigate and detain hundreds of people, but never caught the killer.

But that hasn’t stopped countless people over the decades from claiming they “know” who the killer was. Believe it or not, some of the very famous names that have constantly cropped up over the years are Winston Churchill’s father, author Lewis Carroll and, of course, Queen Victoria’s grandson Prince Albert.

In fact, the list of suspects is near endless, it’s a case of pick a name. Anyone you like.

New books are appearing all the time with their own take on it all. And of course, while you and I – rightly so – cannot walk around accusing someone of murder today, the Whitechapel murders were so long ago and all people involved or suspected long dead, anyone today can blame anyone without retribution or having to show proof.

There are said to be over 100 suspects. Some of the more serious suspects, the highly possible ones that have cropped up time and time again, include the following.

Montague Druitt. He was a barrister and teacher who had an interest in “surgery”. He was said to be insane, and disappeared after the final murders. He was later found dead.

Aaron Kosminski was a Polish Jew who lived in Whitechapel. He was known to have great hatred towards women in general and especially prostitutes. He had homicidal tendencies and was therefore sent to an asylum several months after the last murder.

Severin Klosowski, who later changed his name to George Chapman. Three of his wives died in mysterious circumstances. He was found guilty of murder and executed in 1903. However, it was only after his death that he became a suspect. Chapman’s arrival in London coincided with the first Ripper murder, and he also had surgical training.

James Maybrick was a cotton merchant originally from Liverpool. He died in 1889, after having been poisoned by his wife. According to Maybrick’s own diaries, he claimed that he saw his wife in the Whitechapel area of London with her lover. This sent him into a murderous rage – where he killed five prostitutes. He actually goes on to describe the murders, and ends by saying: “I give my name that all know of me, so history do tell, what love can do to a gentle man born. Yours truly, Jack the Ripper.”

Then, of course, there was James Kelly, who I mentioned last week. Kelly was sent to Broadmoor in 1883 for murdering his wife. He escaped in 1888 just a few months before the Whitechapel murders.

The list goes on and on…

As gruesome as it all was, some good did come out of the killings. For example, it forced an awareness among the wealthier citizens of London’s better areas to the plight of those who lived in the poorer areas and in squalor. In the two decades following the murders, the worst of the slum areas were demolished.

It’s also been said that it was one of the first times that women’s rights, ie their safety, came into the general public domain.

Once depicted as a vast slum area, the east end of London has of course changed dramatically since the 1880s. Despite its transformation, you can still take a Jack the Ripper tour of the area. To learn more about this, go to jack-the-ripper-tour.com

I think I may well take this tour next time I’m in London

To sum up. JTR was either one of the men listed in this column, or he was just a nameless nobody.

That said, what if there is something darker at play here?

It may be similar as in the death of JFK, as in what are we not being told? It has been suggested that the authorities may well have known who “Jack” really was, but it was all buried because he was far too important. Could it possibly have been Victoria’s grandson Prince Albert?

Your guess is as good as mine.

Kind of like the Loch Ness Monster which I wrote about recently, as in we’ll probably never know the truth.

Next week – Never let the facts get in the way of a good story!

Conversation