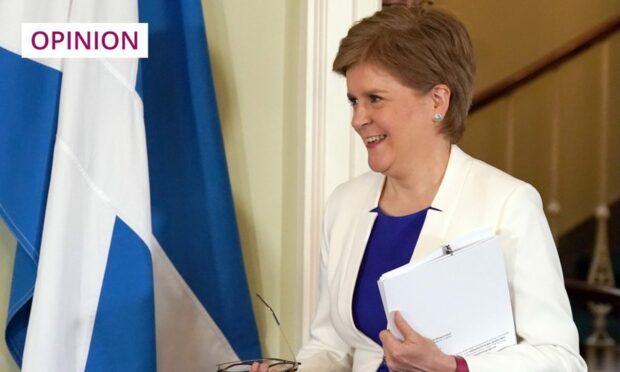

On June 28, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon published the text of her proposed “indyref2” bill.

To get around the problem that a straightforward referendum on independence would very likely be ruled unlawful by the courts as being “ultra vires” (beyond the power) of the Scottish Parliament under the terms of the Scotland Act 1998, Sturgeon has decided on twin tactics.

Firstly, instead of holding a binding referendum, she proposes to hold a merely “consultative” one. Secondly, she referred the issue to United Kingdom Supreme Court the very same day.

The declared aim of the first minister is to get a ruling one way or the other on the lawfulness of the referendum from the Supreme Court as soon as possible.

So, is it all now full steam ahead for a ruling? Perhaps, but, quite possibly, perhaps not.

A bill’s lawfulness should be tested after it has been passed

The difficulty is that it is far from clear that a reference by the Lord Advocate to the Supreme Court of a “devolution issue”, under schedule six, paragraph 34, is the appropriate way to determine the lawfulness of an independence referendum. This is because the Scotland Act already contains a specific procedure for determining the lawfulness of a bill, in section 33.

Under section 33, a challenge to the lawfulness of a bill by the UK Government or the Lord Advocate must be made within “four weeks of the passing of the bill”. But, the present Scottish independence referendum bill has not even been introduced into the Scottish Parliament, let alone been passed by it.

The time to test a bill’s lawfulness is after it has been passed, not before. That fact alone makes it unlikely that the Supreme Court will give a ruling on the lawfulness of the referendum at the present time.

But, there is a further problem in existing law which makes it even less likely that the Supreme Court will decide on the case.

The case of Keatings v Advocate General

In the 2021 case of Keatings versus Advocate General, where Martin Keatings sought and failed to get a ruling on the validity of a possible referendum bill, the Court of Session made it clear that the validity of a bill may only be challenged under the section 33 procedure.

The Supreme Court is, of course, not bound to follow a decision of the Court of Session, but it may well find its reasoning persuasive

Carloway, the Lord President, said in paragraph 60 of the judgment:

“It is important in limine (the legal Latin term meaning at “at the very beginning”) to make a clear distinction between an Act of the Parliament and a bill. Only a provision of an Act can be out with legislative competence. The contents of a Bill cannot be, since a Bill has no legislative force…

“The Act goes on to provide expressly for the scrutiny of Bills at a stage after a Bill has been passed by the Parliament but prior to it receiving Royal Assent.

“It has confined that scrutiny to the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom and then only on the application, within a limited window of time, of the principal law officers of Scotland and the United Kingdom. This is the only method of scrutinising a measure for legislative competency prior to Royal Assent.”

So, applying Keatings, it follows that the current reference would be ruled premature.

We’ve got a while to wait

The Supreme Court is, of course, not bound to follow a decision of the Court of Session, but it may well find its reasoning persuasive. If that were to happen, then it will dismiss the current reference, with the instruction to bring back the issue of the competence of the new referendum bill after it has been passed by the Scottish Parliament.

There is no doubt that the new Scottish independence referendum bill will be approved by Holyrood, given the SNP-Scottish Greens majority, but that will take several months.

Just received this from Johnson (one of his last acts as PM?). To be clear, Scotland will have the opportunity to choose independence – I hope in a referendum on 19 October 2023 but, if not, through a general election. Scottish democracy will not be a prisoner of this or any PM. pic.twitter.com/EAgIVvEuoc

— Nicola Sturgeon (@NicolaSturgeon) July 6, 2022

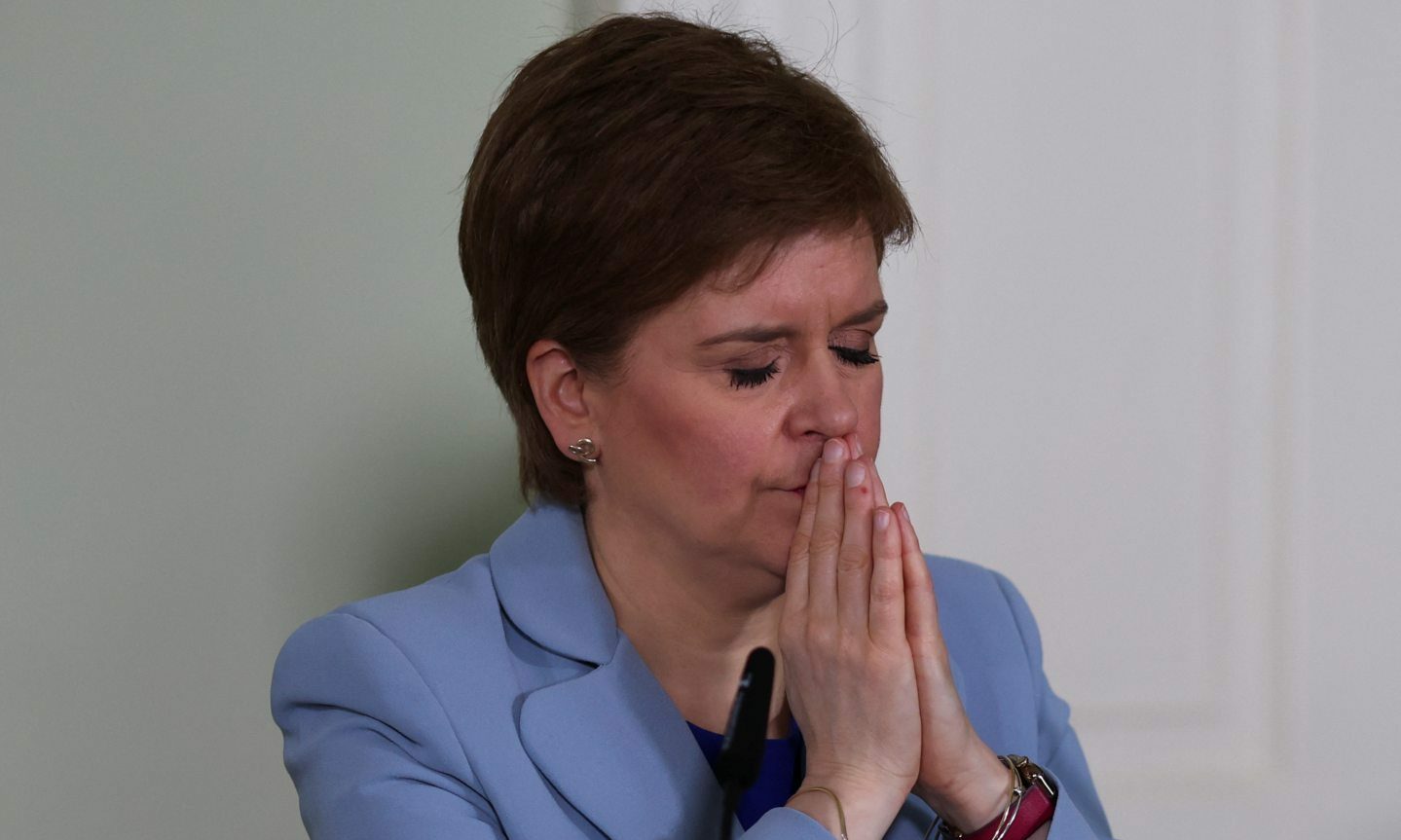

So, we may have to wait some time before the question so urgently asked by Sturgeon as to the lawfulness of the bill can be referred to the Supreme Court for a definitive, legal answer.

When that time comes, which will be after the bill has been passed by Holyrood, then the answer is unlikely but to be to her liking.

Scott Crichton Styles is Senior Lecturer in Law at Aberdeen University

Conversation