It is always salutary to – metaphorically – walk in another person’s shoes, feel the ways the uppers chafe, or pebbles cut through thinning soles.

Years ago, following a spate of prostitute murders in Glasgow, I walked with street girls in the red-light district to write a feature. A police car trailed me constantly, crawling slowly behind. While grateful for their concern, I was frustrated because it hindered my conversations. Besides, the irony of the strenuous efforts to keep me – a middle class, professional – safe when street girls were being murdered did not escape me.

There is, in our society, a tendency to protect the power of those who already have it. We save our carefully-constructed outrage or concern for the ”worthy”, the wealthy and the privileged. To hell with the rest. How easy it is to simply sacrifice them on the high altar of conformity. Don’t fit in? You don’t matter then. The powerful will always be protected over you.

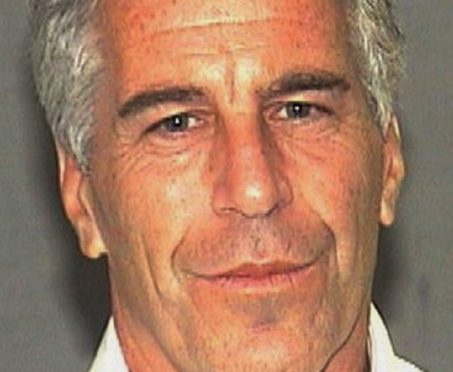

Take Jeffrey Epstein, the billionaire American hedge-fund manager who was jailed in 2008 for having sex with under-age girls. Epstein had friends in high places. Bill Clinton. Donald Trump. Prince Andrew. The scandal reverberated around Buckingham Palace when pictures of Prince Andrew with a 17-year-old girl Epstein was said to have procured were produced as evidence in Epstein’s case. The prince denied all allegations of any wrongdoing. Epstein subsequently spent just 13 months in prison, after coming to the kind of secret, establishment deal that only powerful men get to cut: he pled guilty to reduced charges, and left prison daily to go to his office.

Epstein has now been re-arrested. He owns a private jet, once sickeningly named the “Lolita Express” and the FBI were waiting for him last Saturday when he touched down from Paris. He faces charges of trafficking minors, a prevalent global problem that involves luring vulnerable people into exploitative situations by cajoling, coercion or deception. According to a report last month from the US Department of State, around 25 million people globally are currently suffering at the hands of traffickers.

In the last week alone, I have read about 13-year-old Bangladeshi prostitutes, lured into brothels because nobody cares enough to prosecute those who exploit them; of women trafficked to service New Zealand’s sex trade; of Theresa May declaring modern slavery the greatest human rights issue of our time. Trafficked people in the world now outnumber trafficked arms.

People have become commodities with commercial rather than human value. The profit line dominates – even when there’s a prosecution. Epstein was, and continues to be, the narrative. He was jailed – briefly – but allowed to continue earning. The case centred on his power and his bank balance but I find myself wondering what happened to the girls. Were they simply discarded as the detritus of his wrongdoing? The bit of the story that doesn’t really matter? Who cared enough to protect their lives and earnings? More simply, who cared?

We can only hope that any prosecution this time is different, that our experiences of the Harvey Weinsteins, the Jeffrey Epsteins, the Donald Trumps, make us all wake up to how supine we have become in the face of power. We’ll see. If Epstein’s crimes involved filthy lucre, he might get legally hammered. But exploiting women? Naughty boy, but never mind. ( “…he likes beautiful women as much as I do and many of them are on the younger side,” Trump once said of him, like he was discussing a preference for blonde hair or blue eyes.)

Walking in that red-light district was a revelation. As a child, one woman had been sold to men by her own mother. “Punters despise us,” she spat, her face twisted with fury, “but they don’t realise we despise them from the minute we get in their cars.”

Shaking off the police car, I eventually managed to walk alone with one young woman. She was gentle, articulate, but tortured by drug addiction and self-loathing. She worked to feed her habit – and her pusher – in the way other women work to feed their children. Our conversation was so easy that I realised in another life, we might be friends. We walked up the road together and as I asked how it felt to live her life, something happened that answered me more viscerally than she could. A man walked towards us and as I glanced up, I caught his look. I realised that he thought we were both prostitutes, his expression a combination of curiosity and disgust. In that moment, I felt naked, humiliated – and educated.

I think of those women sometimes when I read stories about people like Epstein. Two years after Epstein was released from jail, Prince Andrew was photographed walking in Central Park with him. The Prince and the predator. And then there’s the prostitute. The hierarchy of human value and human power. But how a person is judged depends on just whose shoes you are walking in – and what underlying values you apply.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter