Of all the developmental milestones your child goes through, speaking is arguably the most exciting.

Few things are more anticipated by parents than being able to communicate verbally with their child.

But what if, after all that waiting, your child still isn’t putting words together?

Whether your child is shorter than their peers, or has less hair, tends not to get parents worked up.

If your child’s friends have started talking, however, while your child is barely babbling, chances are you’ve got that knot in your stomach that only grows with each speechless week.

It’s a feeling I’m familiar with – my oldest child didn’t start saying sentences until he was three and a half.

Everything worked out in the end, in fact I was a late speaker myself. But why do parents worry so much about their child’s speech? Do they need to worry so much? And what should they do if they are concerned?

External pressures and comparisons: ‘Totally understandable’ that parents fret

I spoke to Glenn Carter, Scotland head at the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT). He said it was ‘totally understandable’ that parents fret over their child’s speech.

“I think the reason parents worry is because communication is core to who we are as humans,” said Glenn. “It helps us connect, share our thoughts, our hopes and our love.

“As a parent there is this acute desire to connect with our child. But also, parents instinctively know how important spoken language is for a child’s development, wellbeing and learning, even their future life chances. So if parents feel that that’s impaired in some way, then they’re going to be worried about their child.

“There can also be this external pressure, with a child being compared to other children. Is your child talking as much as this one, and so on.”

‘Significant increase’ in demand for help since pandemic

The issue of children learning to talk is particularly topical in the post-Covid era. Glenn says that post-pandemic, there has been a 20% increase in demand for speech and language services.

The RCSLT recently did a questionnaire with early years practitioners from all areas of Scotland. A staggering 89% of them have seen a significant increase in the number of kids with communication needs. Reduced opportunities for interaction and the wearing of face masks were named as contributing factors.

So what are the red flags that your child’s speech might not be on track, and that they might need help?

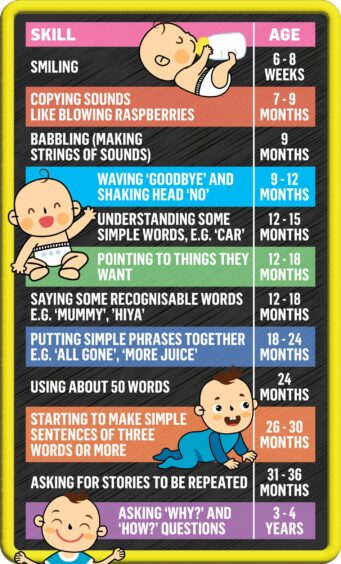

What should my child be doing at what age?

Expect 50 words by age two

“Learning to talk is very complex and it’s no wonder lots of children have difficulties in this area,” said Glenn.

“Things to be concerned about are: can the child enjoy interaction with others? Are they able to understand what people are saying and do they have the concentration to listen, and do they seek out that communication?

“Babbling, pointing, saying odd words are signs that your child wants to communicate.

“You’d expect about 50 words when they reach two. You may not understand all those words, but if they’re words that they attach meaning to then that’s fine.

“But even if they’re not saying 50 words at two, I wouldn’t be concerned about that for another six months or so.”

He added: “Some kids are dysfluent and stammer. That’s often part of the normal development you might expect a younger child to go through. But if it’s going on for a bit longer than you’d expect then you should intervene.”

Girls learn quicker than boys

Glenn gave two pieces of reassurance to worried parents.

Firstly, speech difficulties in young children are far from uncommon. And secondly, it’s an area of child development that can usually be helped with the right intervention. Often simply from parents themselves.

“There are a lot of kids who have communication needs. One in 10 actually, so it is quite common.

“But it’s important to remember that all kids do develop at different rates.

“Interestingly, far more boys than girls have communication needs. There’s a sort of genetic element where boys tend to be slower, and girls capture it much quicker than boys.

“But for those kids with specific language difficulties, if you don’t do something specific about that, that gap can remain, which impacts on their ability to learn.

“Perhaps reassuring for parents is the fact that communication is one area of a child’s development that is most amenable to change, if you do the right things at the right time.

“With the right support at the right time, you can actually have a very good impact on it.

Don’t try and drag words out your child’s mouth

“Generally, key things that parents can do are reasonably straightforward.

“Spend time with your child, talk to them, play with them. And do that without any background noise. I know that can be hard sometimes, but turn off the telly, turn off background noise.

“The way you interact with your child is important. Sometimes when parents are concerned about their child’s speech, they try and drag language out of them. They’ll ask ‘what’s this’, ‘what’s that’, and try to get them to name lots of things.

“What we know in language development is that it’s much better to see yourself as a commentator. Comment on what your child’s interested in and what they’re doing: ‘Oh, you’re pushing the red car.’ But it needs to be what the child’s interested in, rather than about what you think they should be interested in.

“And encourage non-verbal communication as well.”

Help is freely available

There will be times when a child needs external help. An additional reassurance for parents is that, in Scotland, this is freely available through the NHS.

“My message to parents is, if you’ve got a concern, that’s valid,” said Glenn.

“If you would like to be reassured, speak to your service. All speech and language therapy services in Scotland have a helpline. The BBC’s Tiny Happy People is an amazing resource as well.

“I think sometimes what people can forget, certainly if they’re concerned, is that it’s really important to have fun.

“Language really is great fun. And so having fun together, and taking the pressure off, is a great way to develop spoken language skills.”

Conversation