Built in 1888, Peterhead Prison housed some of Scotland’s hardest and most violent men for the next 125 years.

The classic Victorian-built prison which looks like a backdrop to where Porridge’s Slade Prison was filmed, finally closed its doors in 2013.

Thankfully after being closed, it was saved from demolition by people with foresight who also obviously saw an opportunity. And well done to them, for Peterhead Prison is now a museum where you and I can walk its preserved halls and get a feel for what it was like to be not just an inmate, but a prison warder also.

Peterhead Prison is very unlike former Stasi, KGB or more recently Saddam’s prison in Iraq where I have visited. These places were used for torture and nearly everyone locked up was a political prisoner who had simply spoken out against the regime.

Truly awful places where political interrogators literally broke your spirit through fear and interrogation. Peterhead Prison was a legitimate prison for convicted criminals, including armed robbers, rapists and murderers.

The weather that day on my visit? Like the prison itself, grim. Rainy with heavy clouds, it was classic north-east of Scotland weather. Perfect for this visit, for seeing it on a sunny, bright and warm day would have taken away from the reality of what I was about to experience.

I was fitted with an audio explanation device, which was brilliant. As you walked through the prison you clicked the number on your pad according to the number printed at each stage of the journey.

The voice explained various cells and procedures, right from lockup time, canteen duties, the shower block, the laundry room, and of course the act of slopping out. You could view how cells looked like right back to 1888, but for me, I was more interested in the recent history.

Inside the cells, there were no flush toilets.

During the night, each prisoner had to defecate in a bucket or bottle, then each morning they all queued up to pour said contents down the communal toilet on the bottom landing.

Degrading for the prisoners and not a pleasant experience for the warders who had to stand guard while all men slopped out. The stench must have been overpowering.

Degrading for the prisoners and not a pleasant experience for the warders who had to stand guard while all men slopped out. The stench must have been overpowering.

This daily routine was often a cause for violence. All it would take was for one man to ‘accidently’ splash his bucket over the trouser leg of another and all hell would break loose. Slopping out would continue until 2007.

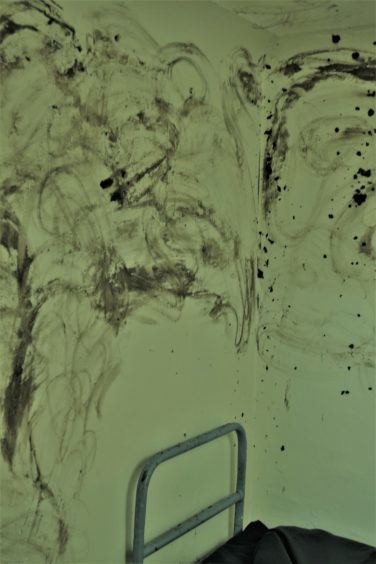

Human excrement was also used in what was known as a “dirty protest”. This was big in the 1970s and 80s and was a copycat version initially used by such men as IRA prisoners in Northern Ireland.

When they wanted to make a protest, make a point, they would smear their individual cells with their own excrement. When officers had to then enter the cell, they would often be subjected to having excrement thrown at them.

The prison has an isolation area where around half a dozen men who were classed as highly dangerous were kept.

If that wasn’t enough, outside in the yard was a single cell where an individual would be sent if he was particularly violent. There was nothing in that cell bar a stone bed to sleep on.

Nothing else. I stood inside there, it was depressing and I think I would have gone insane locked in there for days on end. That said, I’ve been told that some prisoners regarded being in this cell as a badge of honour.

One area of the prison particularly caught my attention. A tiny wing kept for one man. This prisoner was deemed so dangerous, he was kept totally isolated and guarded by three warders.

There is actually a sign on the wall saying that even today the museum authorities cannot discuss this individual. The mind boggles In the hospital wing, I saw the doctor’s room, the dispensary and a dentist. As well as having to deal with prisoners’ injuries from the likes of attacks and stabbings, doctors had of course also to tend to everyday health issues such as cancer and heart attacks.

Can’t have been easy under these conditions, and with many prisoners being drug offenders and drug dependant, the security around the dispensary must have been intense.

But I’ve been told that it was, and still is, relatively easy for prisoners to smuggle drugs into prisons. Often brought in by visiting family and friends, drugs were sometimes kept inside condoms which the prisoner swallowed, then hopefully later excreted out the other end once in the privacy of his cell.

But if the condom burst while in his stomach . a massive overdose and often a painful death awaited the prisoner. Today, with mobile phones and flying drones, prisoners often get contraband literally dropped in for them. I’ve seen documentaries on this. It’s remarkable.

As I walked the corridors and took in the Victorian-style iron staircases and caged-in environment, I looked up at the security mesh that stopped people jumping from a landing or throwing someone else off, it really did feel like being in Porridge. If a harsh commanding Scottish voice suddenly barked out, “Fletcher!” I don’t think I would have batted an eyelid.

Joking aside though, could I be a prison officer? No, I could not. Far too confined, even though of course they are allowed to go home at night. And as for constantly being worried about being attacked or stabbed? No thanks. Brave men and women, in my view.

It’s an ongoing discussion in our society, do we send people to prison for punishment or rehabilitation? It’s so very easy to think that prisoners should be punished for their crime and that’s it. In some ways, that makes sense and is what I used to think.

However, the more I see of the world, the more I think rehabilitation is absolutely vital. If a prisoner, despite what he may have done, is due to be realised in 10, five or three years, surely if all we do is punish him and give him no hope, he is going to come out even harder than when he went in and will only hate society all the more and want to extract revenge.

I’m certainly not a so-called bleeding-heart liberal, but punishment and nothing else for prisoners seems totally counterproductive to me. But of course, I’m no expert in such matters.

I have to admit that on my car journey to the prison, I was slightly sceptical as places such as this can turn out to be a disappointment. They sometimes feel faked, made up, trying too hard, like say one of those awful themed Irish pubs that’s no more Irish than I am.

But Peterhead Prison Museum is excellent and if you’re remotely interested, I thoroughly recommended a visit. It’s a fascinating insight into real prison history. Marks out of 10 for this museum/exhibition? An easy 10 out of 10.

There has been much violence over the years in this building, way too much to list. There is, however, one incident that will forever make Peterhead Prison infamous.

In 1987, a massive riot broke out and while on duty, prison warder Jackie Stuart was taken hostage. For five days he was held by violent men and paraded in front of the authorities and TV cameras, a terrifying 75 feet up on the rooftops.

During the ordeal, Jackie was stabbed, badly beaten and led by a chain around his neck. At one point, those holding him forced lighter fuel into his pockets and threatened to set him alight.

Thirty-one years later, Jackie Stuart is now pushing 90, yet thankfully alive and well, and I am privileged to have met him. Last year he wrote a book on what happened to him. I bought and read this book, which is a very personal insight by a very humble man into what must have been a terrifying ordeal.

Jackie then agreed to talk with me and go into more depth on what happened to him during those five days in 1987…

To contact George directly about any of his columns, email nadmgrm@gmail.com.