They were the Allied prisoners of war who were as keen as mustard to keep the heat on their German captors during the Great War.

Working closely with an elderly Church of Scotland minister in a north-east fishing village, they established a secret code which was communicated between the soldiers and despoatched to the War Office back home.

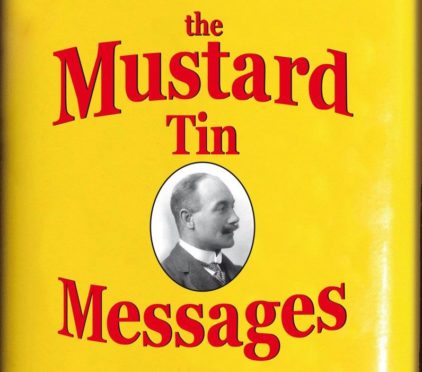

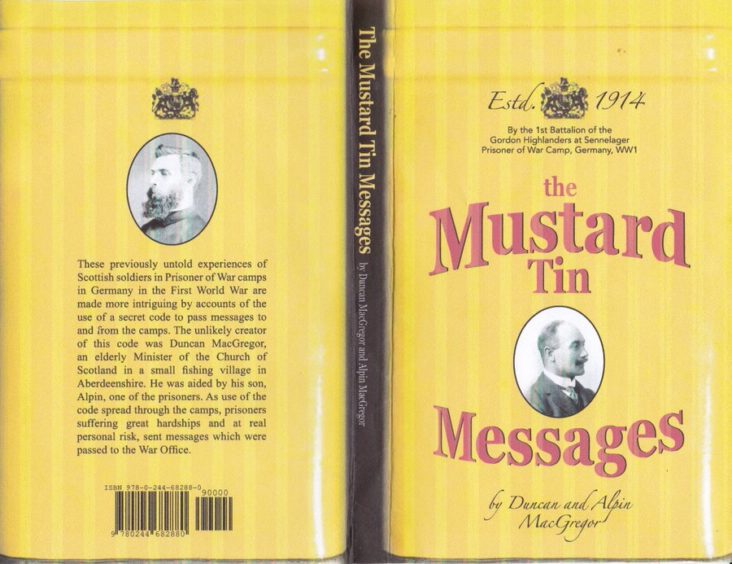

And now, the remarkable story of how the Gordon Highlander troops defied their adversaries has been disclosed in a new book “The Mustard Tin Messages”.

The man behind the code, Rev Duncan MacGregor, served his parishioners in Inverallochy and was spurred into action when his son was taken prisoner in 1914.

Alpin MacGregor, a sergeant major in the Gordon Highlanders, was among the first soldiers to be sent to the front to fight and his battalion were involved in the battle of Mons in Belgium.

However, after the British forces were surrounded and forced to surrender, around 700 soldiers were captured, 500 of them Gordons troops and they were subsequently interned at Sennelager in northern Germany.

His daughter recalls in the book: “It was in early 1915 that he [Alpin] began to notice certain peculiarities in his father’s letters.

“Eventually, he realised that by using the last letter in each sentence, a message was formed. In his next letter home, he used this formula to convey the following message: ‘send news in a mustard tin’.

“The next parcel sent from home contained a tin of mustard with a closely-written synopsis of the progress of the war.

“It also suggested using one word in every sentence to convey messages that would be put at the disposal of the intelligence service at the War Office.

“The letter also said a cocoa tin would be included in every parcel, into which newspaper cuttings would be inserted with as much news as possible. And so began the ‘cocoa press’ in the Sennelager camp.”

The prisoners faced myriad privations during their confinement and constantly had to show courage in adversity, but they refused to buckle as the conflict continued.

Yet there were several occasions where Alpin MacGregor was nearly snared by his captors as he played a dangerous game of cat and mouse.

Mrs MacGregor Isles said: “One morning, the prisoners were startled by the guards shouting ‘Raus, raus’ [Out, out]; they had to respond quickly to the situation and my father found himself out in the snow waiting to be searched, only to realise that he had a notebook in his pocket, with incriminating evidence of the code.

“It was only some quick thinking which helped him to evade detection.

“As soon as the men got back to the huts, which had also been searched by the guards, he destroyed the evidence and distributed the words between his copy of the New Testament and a Golden Treasury.”

He collected his thoughts in a journal after the conflict was over and they reflect his mixed feelings at being imprisoned.

On the one hand, he was determined to assist the war effort in any way he could.

But he was also frustrated at being stuck behind fences and barbed wire and facing up to the reality there was only so much he and his comrades could achieve.

He recalled: “My efforts, however futile they may have been, helped to keep my mind healthy during what was a wretched period of my life.

“I have my own private satisfaction in the fact that, even as a prisoner of war, I at least tried to serve.”

He remained in the army after the First World War and was posted to Mesopotamia in 1923, prior to returning to Scotland in 1926 and getting married the following year to Mary Campbell, as the prelude to the couple having five children.

Mrs MacGregor Isles was one of these and she believes it is still important to honour the many servicemen who spent years in prison camps.

She added: “There is no doubt that POWs are an often forgotten group.

“Yet hundreds of Scottish soldiers from the north and north east were held prisoner for years and many of them suffered brutality and deprivation.

“But, by use of secret messages and a code devised by the scholarly minister of Inverallochy, Duncan MacGregor, they tried to frustrate the enemy’s war effort.”

The book is available from LuLu books at www.lulu.com/shop with the Search: Mustard Tin Messages.