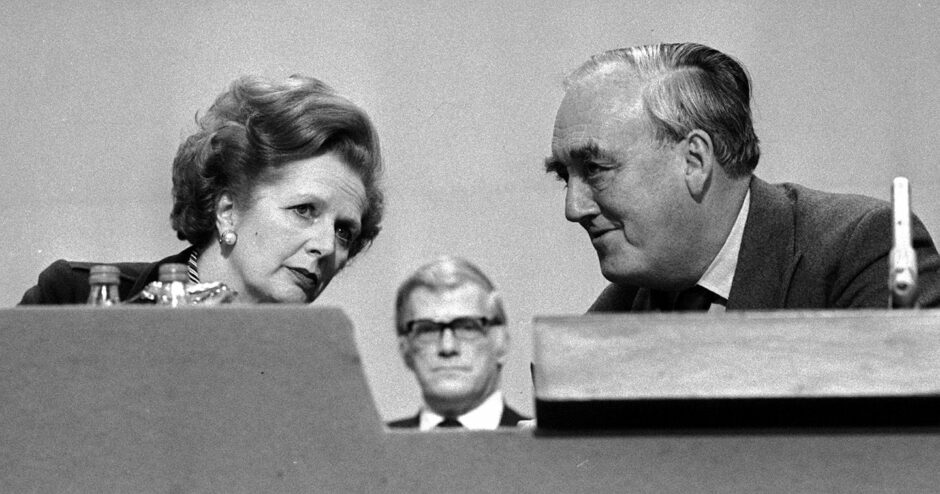

Viscount ‘Willie’ Whitelaw has been coming to mind lately – even though he died in 1999. He was a ‘Tory Grandee’ in every sense, holding senior government and party positions, rising to become prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s de facto deputy.

This of course led to the Iron Lady’s famous declaration “Every prime minister needs a Willie.”

To many in Scotland, Whitelaw was a quintessentially English figure. Educated at Wixenford School in Berkshire, a private preparatory school for Eton, then on to the academically prestigious Winchester College before ‘going up’ to Trinity College, Cambridge to study law and history.

In fact, he was brought up by his mother in her family home at Nairn, when he wasn’t away at school. He didn’t know his father who died in 1919, the year after his birth, but from whom he was to inherit the Gartmore and Woodhall Estate in Dunbartonshire. The Whitelaws had bought the land in the middle of the 19th century.

But it isn’t Willie Whitelaw’s ‘Scottishness’ that has been the subject of reflection, rather his commendable commitment to the democratic process. In particular during the events following the general election of 1974. Whitelaw had been a prominent member of Edward Heath’s government from 1970. He served as Leader of the House, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland and Secretary of State for Employment.

‘We must trust in the will of the people’

In that last job, he had been challenged by considerable industrial unrest, leading to a three-day week to conserve electricity in the face of a miners’ strike. Heath decided to go to the country. It was billed as the “Who Governs?” election, the options being the government or the unions. As has been said, it was a stupid question and he got an even stupider reply – a minority Labour government. The Tories lost 28 seats, although they had won marginally more votes – 226,564 (which didn’t include this writer’s). The final result was Labour 301 seats, the Tories 297 and the Liberals 14.

But Heath was determined to cling on with support from the Ulster Unionists, and the Liberals. He tried to negotiate with them over the following four days. In the middle of this period of uncertainty, Whitelaw was interviewed. He didn’t defend Heath’s actions, saying simply: “We must trust in the will of the people.” He knew what was right.

Labour might not have won a majority, but the Tories had lost theirs, and with it the right to govern. (Theresa May suffered the same fate in 2017, but hung on till 2019 during the parliamentary Brexit madness, with support from the Democratic Unionist Party). The failure of Heath’s negotiations with the Liberals, opened the door of 10 Downing Street to Harold Wilson again.

Whitelaw’s commitment to the peaceful transfer of power as the cornerstone of democracy, was in such contrast to the last President of the United States. The malignancy of Donald Trump’s refusal to trust in the will of the American people has metastasized and is now threatening the vital organs of democracy. More than 370 Republican candidates in this week’s midterm elections had already joined in Trump’s 2020 election denial. Some even refused to say whether they would accept the result, if they lost.

Attack on US democracy

Their refusal not only to accept that their electoral apparatus had worked fairly, but also that their courts had verifiably said so, has been pernicious. Reuters reported: “Following President Joe Biden’s swearing-in on Jan. 20, (2021) a Facebook post shared over 6,140 times has said: ‘Not one court has looked at the evidence and said that Biden legally won. Not one’. This is false: state and federal judges dismissed more than 50 lawsuits presented by then President Donald Trump and his allies challenging the election or its outcome.”

The refusal to accept any event or decision not to their liking can be anything other than false, seems alarmingly embedded in significant sections of the Republican Party, as well other parts of society. It was violently demonstrated in the storming of the Capitol on January 6th last year.

Even the attempt to murder Nancy Pelosi’s husband Paul last month doesn’t seem to be ringing many alarm bells. As Speaker of the House of Representatives, she is third in line in the leadership hierarchy, behind the vice president. She was the intended target of the attack, but somehow that is not being read as an attack on American democracy.

With a grateful heart I thank all who sent kind words and prayers for Paul. It’s a long road but he will be well.

Our security, our Democracy, our planet, our values are on the ballot. Believe that we will win — and help Get Out The Vote to make it so.-NPhttps://t.co/sWs0cfdQJN

— Nancy Pelosi (@TeamPelosi) November 4, 2022

The Republican Party was the party of Lincoln, the party that freed the slaves. But too many in it today are persuaded by the self-idolatry of one man.

The founding fathers and those framing the constitution obviously didn’t anticipate that election results would not be accepted by losers. A pledge to do so should be a legal requirement for all candidates. It could be called Donald’s Law. But until then, the US appears in desperate need of a Willie.

David Ross is a veteran Highland journalist and author of an acclaimed book about his three decades of reporting on the region

Conversation