I always forget how great voting feels until the moment comes around again.

I’m caught unawares by the emotions that accompany placing your X in the box – the sense of community and responsibility, of being a part of something bigger than yourself, moistens my eyes. From the volunteers manning the polling station, to the steady flow of people arriving at the doors, to the physical act of voting itself, elections mark a profound coming together.

Whatever the outcome, voting matters. If your side triumphs, then you’ve done your bit to put the right people in charge. If it loses, then you’ve still registered your resistance, in however small a fashion. It’s the taking part that counts.

There are five votes in my lifetime that have affected me more than the others. The unlined, lithe young man who voted Labour in 1997 did so with an overwhelming sense of excitement and optimism. The devolution referendum came freighted with history. In the independence referendum, my No vote was deeply felt, as was my No to Brexit.

And then there was the first election to the Scottish parliament, on May 6, 1999. Today marks the 25th anniversary of that occasion.

Labour was always going to win, and Donald Dewar was always going to be first minister. There was security in that – Labour had created the parliament, and Dewar, as its key architect, was the obvious person to be trusted with husbanding devolution through its earliest years.

Piercingly smart, experienced, bookish, reliably untucked, and drolly funny, Dewar provided the new institution with a comforting, lawyerly, churchly father figure. He was so unmodern in aspect that he might have been sent forward from a 19th century kirk to keep us right.

A Labour-Lib Dem coalition was the right kind of government for the moment, too. It soothed Scotland’s social democratic soul. It was decent, well-meaning, and fully believed in devolution.

Reality of Scottish parliament didn’t live up to excitement

The current Holyrood building was some way off completion, and so the new parliament met in the Church of Scotland’s austere General Assembly Hall on Edinburgh’s Mound.

We hacks who covered its doings for our daily bread were located across the Royal Mile, in an ancient, tall, narrow building with a dangerously steep stone staircase. I was on the top floor which, if nothing else, made every day leg day.

I look back on it all fondly, even if the reality was more mixed and, at times, frustrating. A bagpiper set up residence outside the press building and would blare away for hours at a time – this was charming at first, but soon led to furtive discussions about the creation of a “sniper for the piper” fund.

The excitement of being at the heart of an important democratic moment in Scotland’s history quickly faded, as the reality of parliament’s focus and limitations clarified. Some MSPs were more impressive than others (nothing changes). It wasn’t the most exciting place, and lacked the shimmer of global import that quickens the blood when one enters the Palace of Westminster. The Dog Fouling (Scotland) Act became, somewhat unfairly, a measure of devolution’s ambitions.

Today’s Holyrood is angry and divided

Now, 25 years on, there is discussion about what a quarter-century of Holyrood has amounted to. Has it even come anywhere close to fulfilling its potential? Has it all been worth it?

To be clear, the Scottish parliament is going nowhere. Those who grumble about its necessity perhaps forget how peripheral Scotland was at Westminster, the lack of heat and light and time applied to policy, all decisions taken by a coterie of Tory men who most Scots hadn’t voted for. That was a sub-optimal situation.

What we have now is an institution that is flawed, angry and divided. One that, for too many years, has arguably been focused on the wrong things.

But you could say the same for Scotland as a whole. In fact, you could say that this is merely one symptom of wider Western society. Look at the state of the US, of Westminster, of the broad rise of populists focused on identity politics and the inculcation of division. Scotland has hardly been alone in gazing intently at its own navel.

We have the power to change direction

Politics across the developed world has been through disruption after disruption, as it has confronted economic decline, environmental panic, demographic deterioration, technological change and the shifting of power eastwards.

Nothing lasts forever – even SNP hegemony – and, ageing and weary as I am, I remain an optimist

If this drove America towards Trump, and England to Brexit, it led north Britain to the consideration of independence. We have elected SNP governments for two-thirds of devolution’s lifespan, and those governments have inevitably concentrated on breaking up the UK. Of course they have – it what’s they’re for. And it’s what the voters chose, over and over again.

This is what democracy means. The electorate gets what it wants. Many have wanted to talk about, and vote (and vote again) on independence. The state of our schools, hospitals and economy came a distant second. We are now paying the price for that neglect.

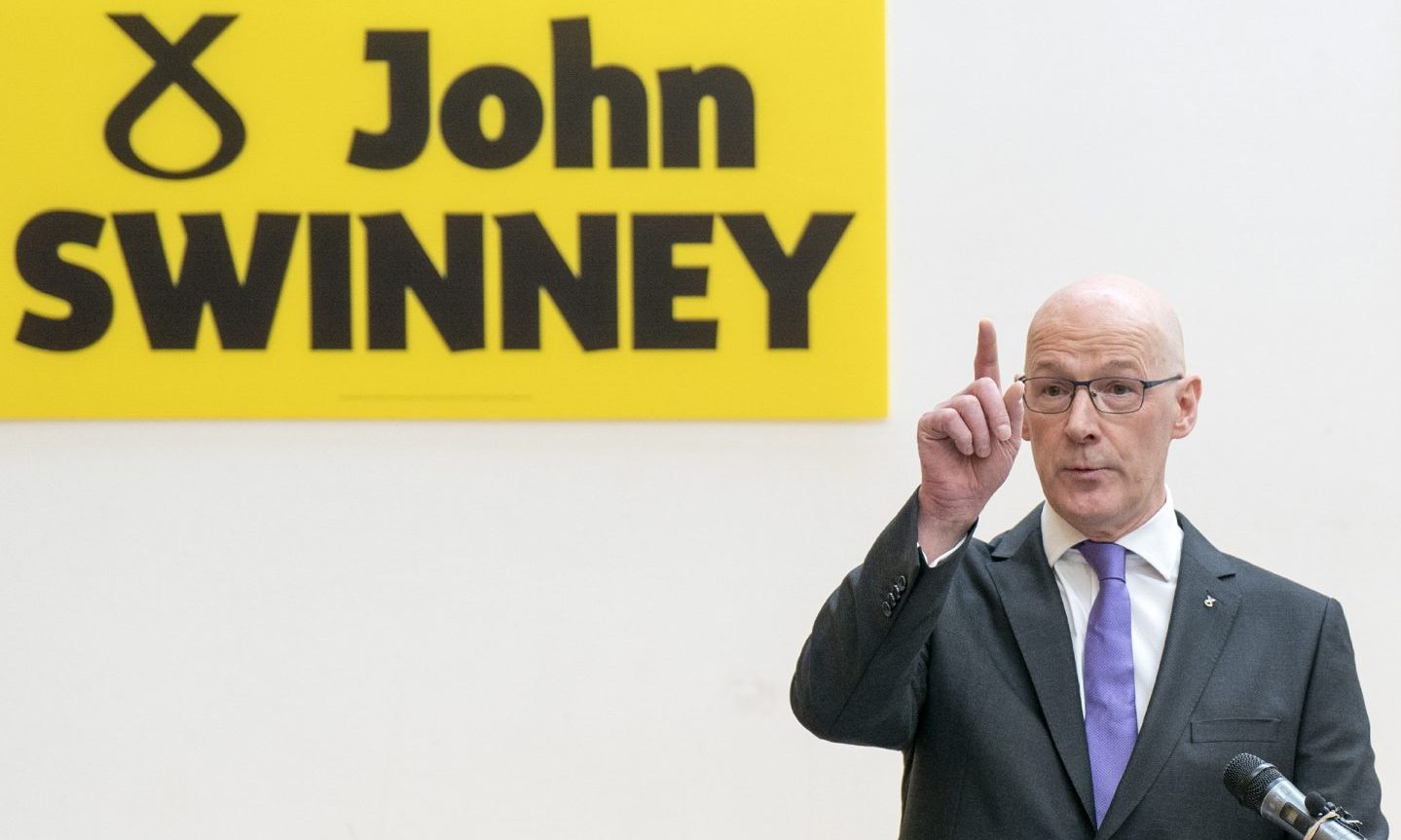

Perhaps John Swinney will shift the dial on this – he’d better, if he wants to avoid getting walloped at the general and Holyrood elections. Perhaps he won’t. But, as the polls shift, this matters less than the welcome sight of democracy correcting itself.

Nothing lasts forever – even SNP hegemony – and, ageing and weary as I am, I remain an optimist. Holyrood is, ultimately, an instrument of our will. If we want its next 25 years to be better than its first, we must vote for it.

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank, Reform Scotland

Conversation