There’s a certain symmetry to the fact that a quarter of a century into devolution, a quarter of votes remain unconvinced by the entire project.

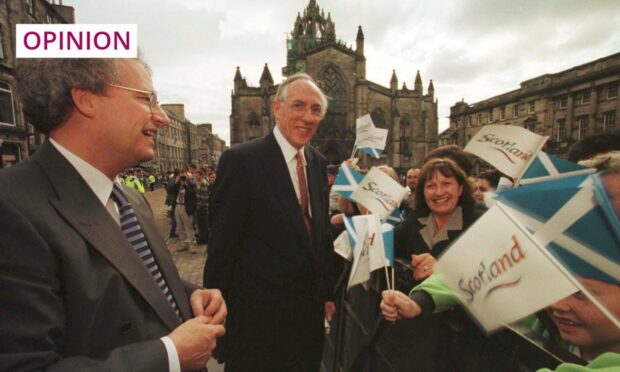

The Scottish parliament turns 25 this year, which brings back memories of that magical first day – the speeches by Donald Dewar and Winnie Ewing that gave it poetic and historical weight, the singing of Burns in the chamber, how Sean Connery shouldered me aside as we passed each other in one of Edinburgh’s narrow closes.

It was a moment of optimism, hope and renewal, and if Holyrood has failed to live up to those early expectations, that was probably always going to be the case. The questions that confront us today are just how far short it has fallen, and why.

A poll by Norstat at the weekend found that while 50% of Scots believe devolution had been good for us, 26% take the opposite view. This latter figure includes almost half of unionists. In 2009, Holyrood’s 10th birthday, 70% approved of devolution compared to 18 per cent who said it was bad.

There has, then, been a decline in positive public sentiment, and this is unlikely to surprise you. The past decade has seen Scottish politics become riven by division, constitutional and otherwise.

The parliament chamber itself – set up in horseshoe formation rather than Westminster’s two sword’s lengths separation, to encourage more constructive behaviour – is now a place of entrenched, warring camps. At times, it has made its sister by the Thames resemble a yogic retreat in comparison.

Plans for independence, but not public services

We can blame the SNP for this shift. The party’s years-long dominance has seen it relentlessly advance the case for independence, almost regardless of the circumstances that have pertained. We’ve had one plan for a second referendum after another, the belligerence of which approach has repelled as many Scots as it has attracted.

There has been neglect of the economy and the public services – reform would make too many enemies among potential independence supporters – which I find hard to forgive.

But it’s also true that the Nats have, in one fashion or other, won all the elections they’ve fought. They have been by miles the most popular political party, and by far the most effective. In the end, it was the voters that chose this confrontational state of affairs.

And perhaps no wonder. During much of the SNP hegemony, Labour stumbled from one disastrous experimental leader to another, while the Conservatives in power at Westminster seemed gradually to take leave both of their senses and any sense of decency. Throw in Brexit, and it might be of some surprise that Scotland hasn’t already quit the UK.

But we haven’t, and with good reason. For the majority of voters, the doubts around separation have never successfully been addressed. The tumble of civil-service-drafted independence papers currently emerging from the Scottish Government have skirted unsatisfactorily around the problems.

Politicians must take their share of the blame

The cost-of-living crisis has properly put the wind up people. And the departure of Nicola Sturgeon, followed by the crashing of her once stellar reputation, the mediocrity of Humza Yousaf, the relentless wave of scandal surrounding the ruling party, plus the return to credibility of Labour are all serving to make voters turn away, for now at least, from placing the constitution at the centre of their voting habits.

There are, of course, some whose disillusionment with devolution is long-standing – they didn’t want a parliament in the first place, and have seen little to change their minds in the decades since. But the politicians themselves must take their share of the blame for rising disaffection.

Things are now so bad that many medics worry the health system will be lucky to survive the decade

Imagine what our education system might look like today, had MSPs from the off agreed a 25-year plan to make it one of the best in the world. Generations of children have been failed by ministers and governments who have been too scared of the unions and the so-called “experts” to tackle the fundamental problems in our schools. The recent Pisa findings shamefully hammered home how we are falling behind much of the developed world.

Much the same can be said of the NHS: a sacred cow which successive administrations have placed on a pedestal rather than address the strains that have become increasingly evident. Things are now so bad that many medics worry the health system will be lucky to survive the decade.

Direct democracy is necessarily messy, imperfect and expensive

The parliament itself has hardly been a vibrant fulcrum of democratic accountability.

The revising function, supposed to be carried out by the committees in the absence of a second chamber, has comprehensively failed due to those bodies’ politicisation. As a result, legislation is too often badly thought through, badly drafted, and simply fails to achieve its intended impact. The executive is too powerful, at the legislature’s expense.

For all this, I’m not one of those who would see devolution junked. In a sense, Holyrood has faithfully mirrored a nation that has been angrily divided – we are evenly split on independence, on high taxes, on whether the SNP or Labour would make the best government, and more.

Direct democracy is necessarily messy and imperfect, and also expensive. But it is, always and everywhere, a bulwark against worse. And just imagine how things would feel were – absent Holyrood – a Tory Scottish secretary still running the nation from Whitehall.

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank, Reform Scotland

Conversation