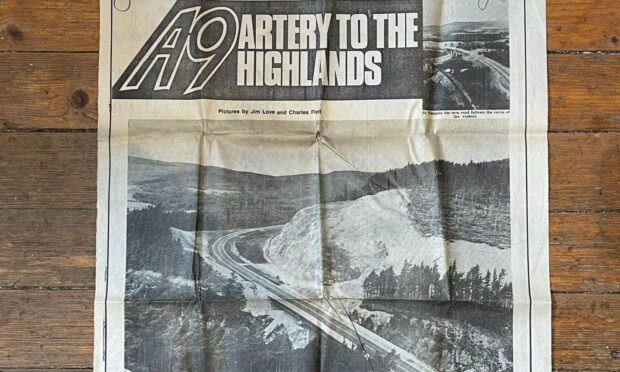

Ahead of its completion in 1982, the long-awaited new A9 was hoped to be the ‘artery of Scotland’, giving lifeblood to north communities.

But in the decades that followed, it’s been more associated with bloodshed and heartache.

The A9 as we know it was obsolete before it was even built — commuters and politicians alike pleaded for a dual carriageway as far back as 50 years ago.

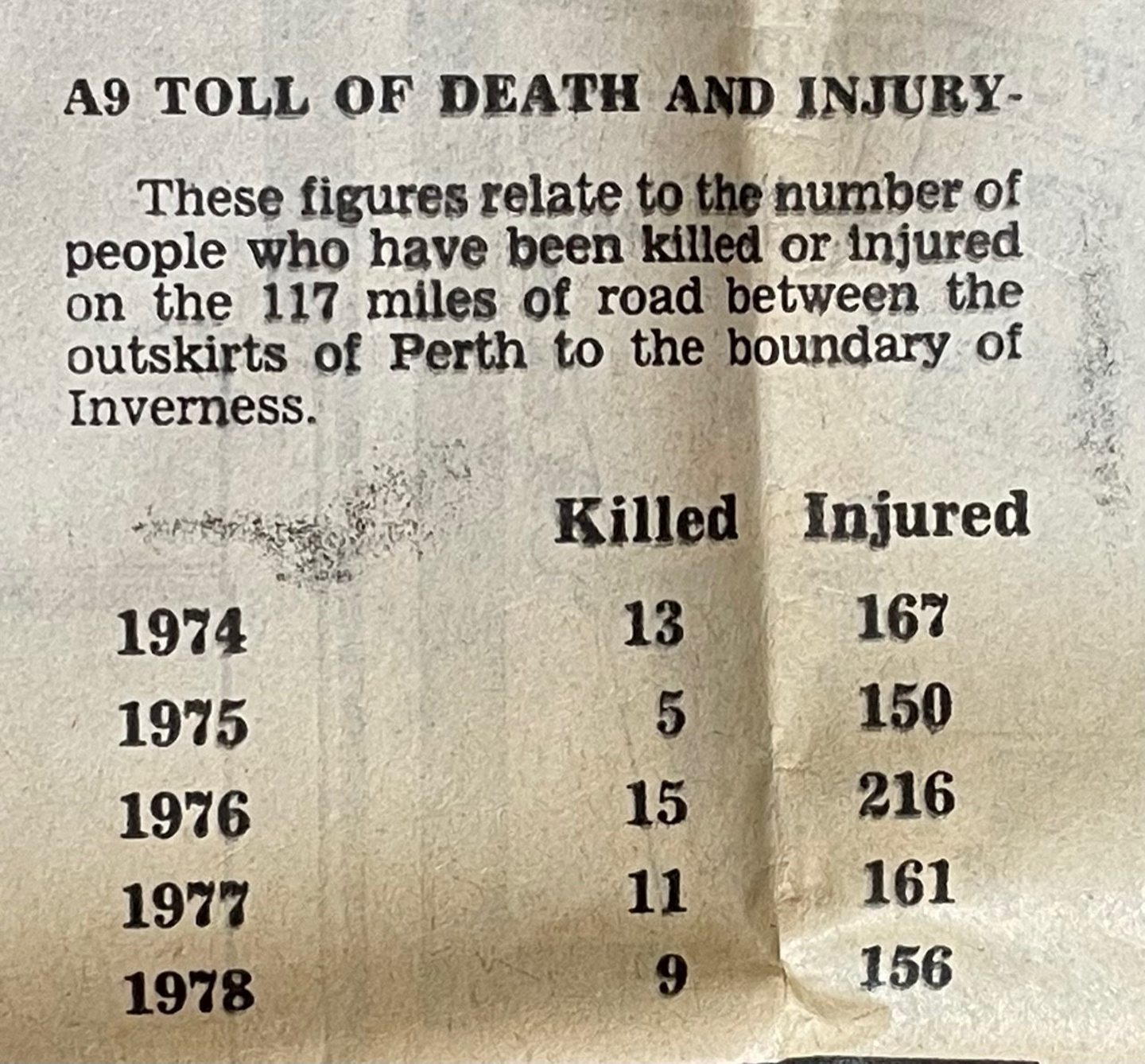

They warned people would die, and hundreds have.

Generations of grief without A9 dualling

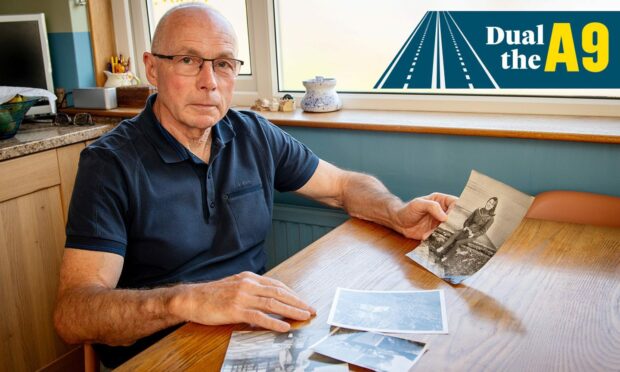

The P&J has never stopped listening to these communities where generations of grief has been perpetuated through an inadequate road.

For half a century, our Highland coverage has regrettably been punctuated by tragedies on the A9.

And of course the repeated heartfelt pleas and broken promises that followed.

This story you’re reading was supposed to be an overview of the P&J’s historic coverage of calls to dual the A9.

But to condense thousands of stories and anguish into one article would do a disservice to the communities and families who have suffered.

Instead, this is the first in a lookback series about appeals to dual the A9 — and the grim legacy that came from turning a blind eye to campaigners.

Upgrade didn’t include dual carriageway

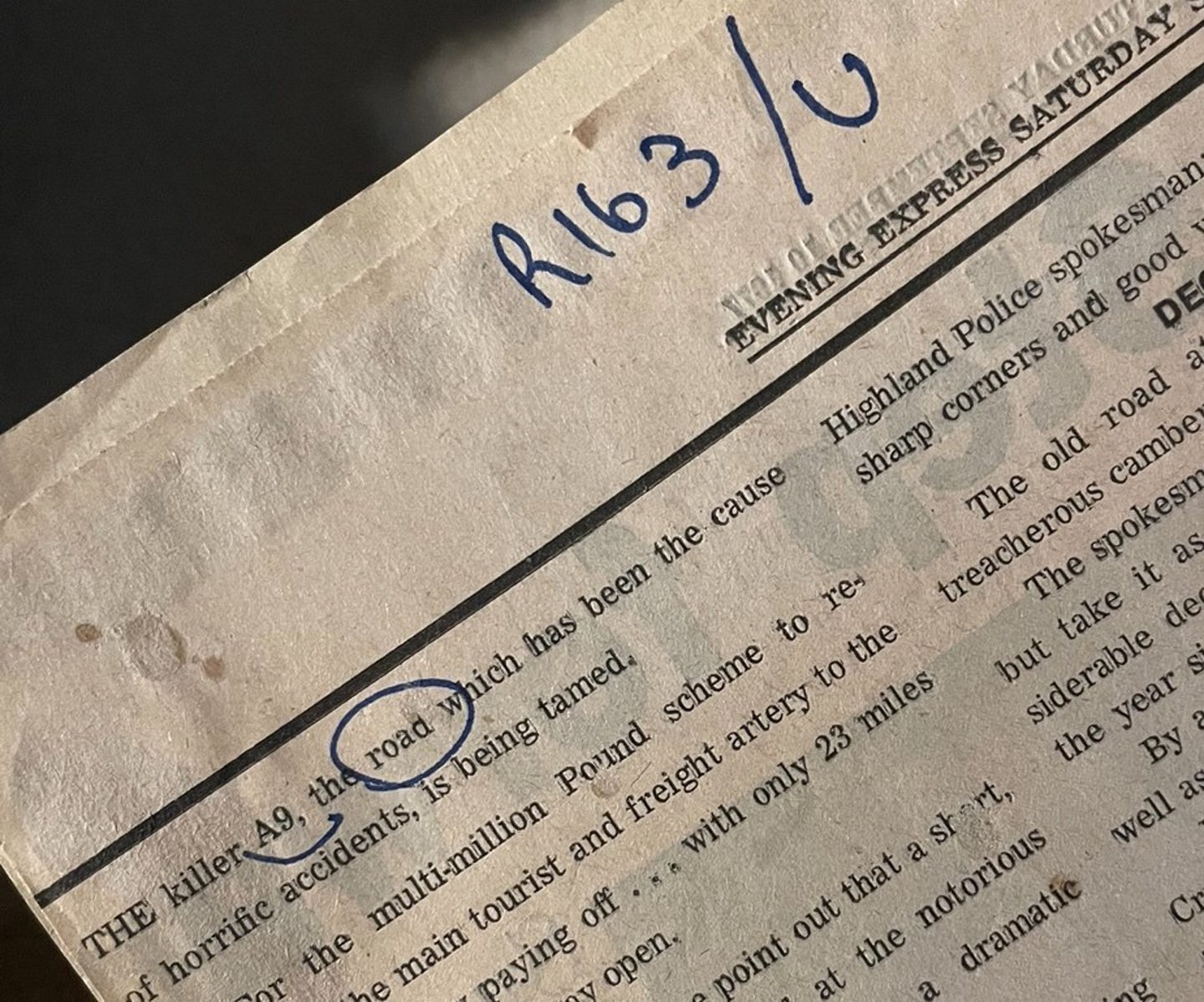

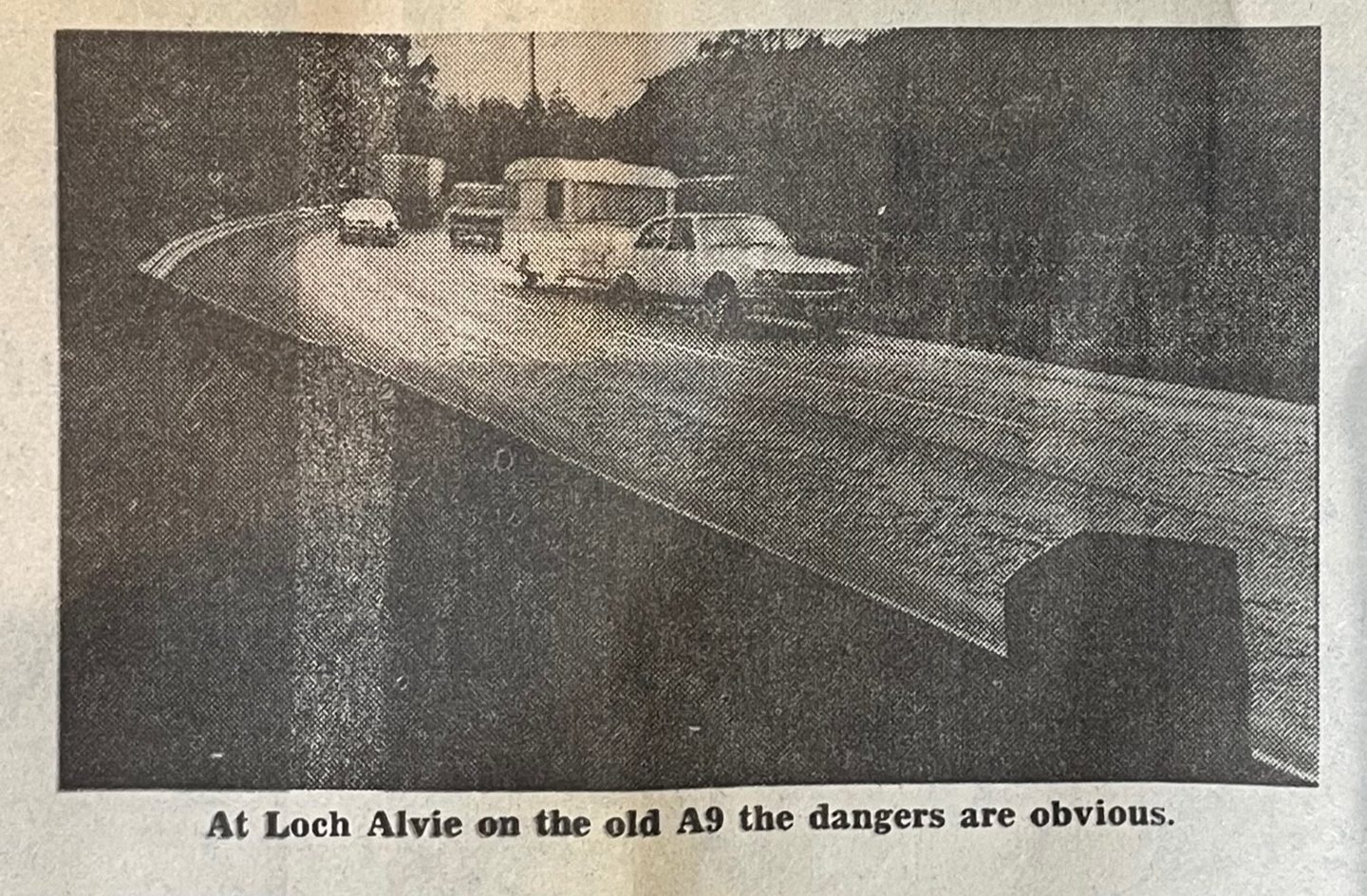

The trunk road has long been dubbed ‘the killer A9’ – an unenviable, but not undeserved nickname first mentioned in the Evening Express in 1977.

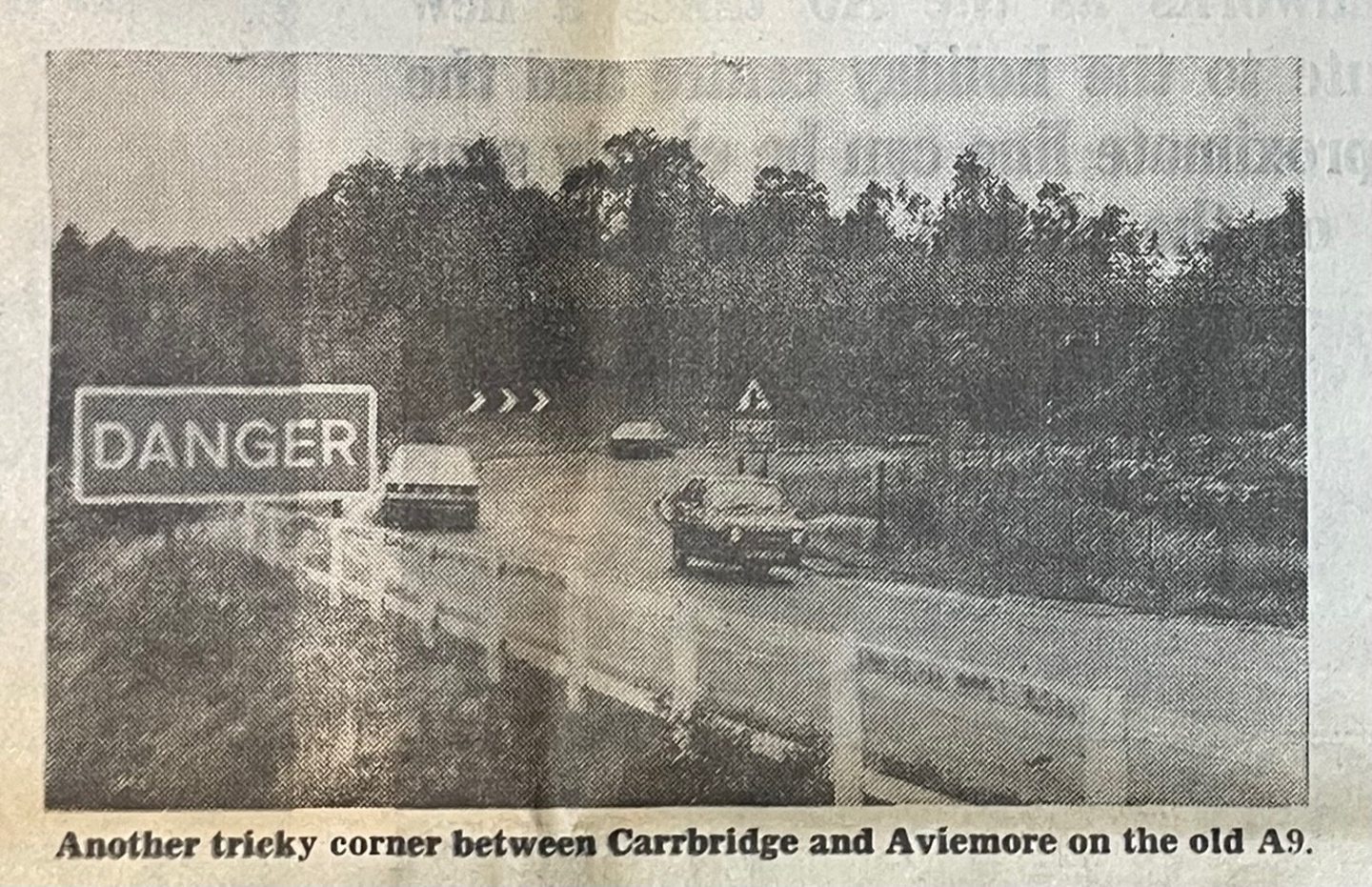

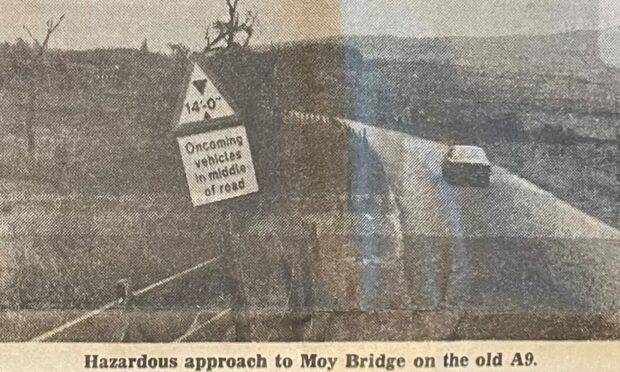

Serious concerns had been raised in the decade before about the dangers of driving on the route.

A white paper was issued by the UK government in 1970 suggesting the road was in dire need of an upgrade.

The need for improvement was accelerated by the discovery of North Sea oil, with industrial developments already under way in the north.

Within two years, plans were announced to modernise the A9 — but they didn’t include dualling it.

Single carriageway instead of dualling A9 was dubbed an ‘insult’

Scottish Secretary Gordon Campbell announced a £10,000,000 single-carriageway improvement scheme for the Perth to Inverness section of the A9 in May 1972.

People were up in arms, and even the Evening Express editorial found the lack of dualling incredulous.

Bill MacKenzie, political director of the Scottish Liberal Party, said it was “simply not good enough for present, let alone future requirements”.

He described the plans not to dual as “absurd”.

And added: “The Treasury will rake in many millions of pounds from North Sea oil revenue and indeed has already netted more than £30,000,000 in rent money alone.

“Against this background the present single carriage-way scheme is nothing short of an insult.”

The A9 would be ‘a speeded-up single-carriageway death track’ without dualling, warned MP

Another fierce and outspoken critic was Dr Gavin Strang, the Labour MP for Edinburgh East, and opposition spokesman on Scottish affairs.

In August 1973, he raised his concerns with George Younger, parliament under-secretary for Scotland.

He said: “To upgrade the road without providing a dual carriageway, is in my view, likely to lead to more accidents rather than less.”

Dr Strang also suggested a motorway-standard A9 would futureproof the region by allowing the development of industries outwith oil and gas.

He added: “If we are to obtain a more even spread of jobs throughout the UK then it is imperative that we massively improve Scotland’s infrastructure.”

But his primary concern was safety.

The following month he reiterated his fears and said: “We should settle for nothing less than a dual carriageway.

“We do not want a speeded-up single-carriageway death track.”

And half a century later, his words are echoed by campaigners today.

His bleak predictions came true.

Councillors criticised ‘out of date’ A9 plans

Councillors shared Dr Strang’s view at a joint Perth and Kinross County Council meeting in October 1973.

They described the Scottish Development Department’s (SDD) A9 plans as “out of date and without foresight”.

The SDD said: “The eventual aim is a complete dual carriageway along the whole length of the road. To achieve this immediately, however, would have meant slower construction and more expense.”

But convener Mr IA Duncan Millar hit back, and said the government had made “a fundamental error”.

Kinross councillor John Kidd went further, he said the council “had been too gentlemanly over the A9 and had worn velvet gloves when they should have used a fist of mail”.

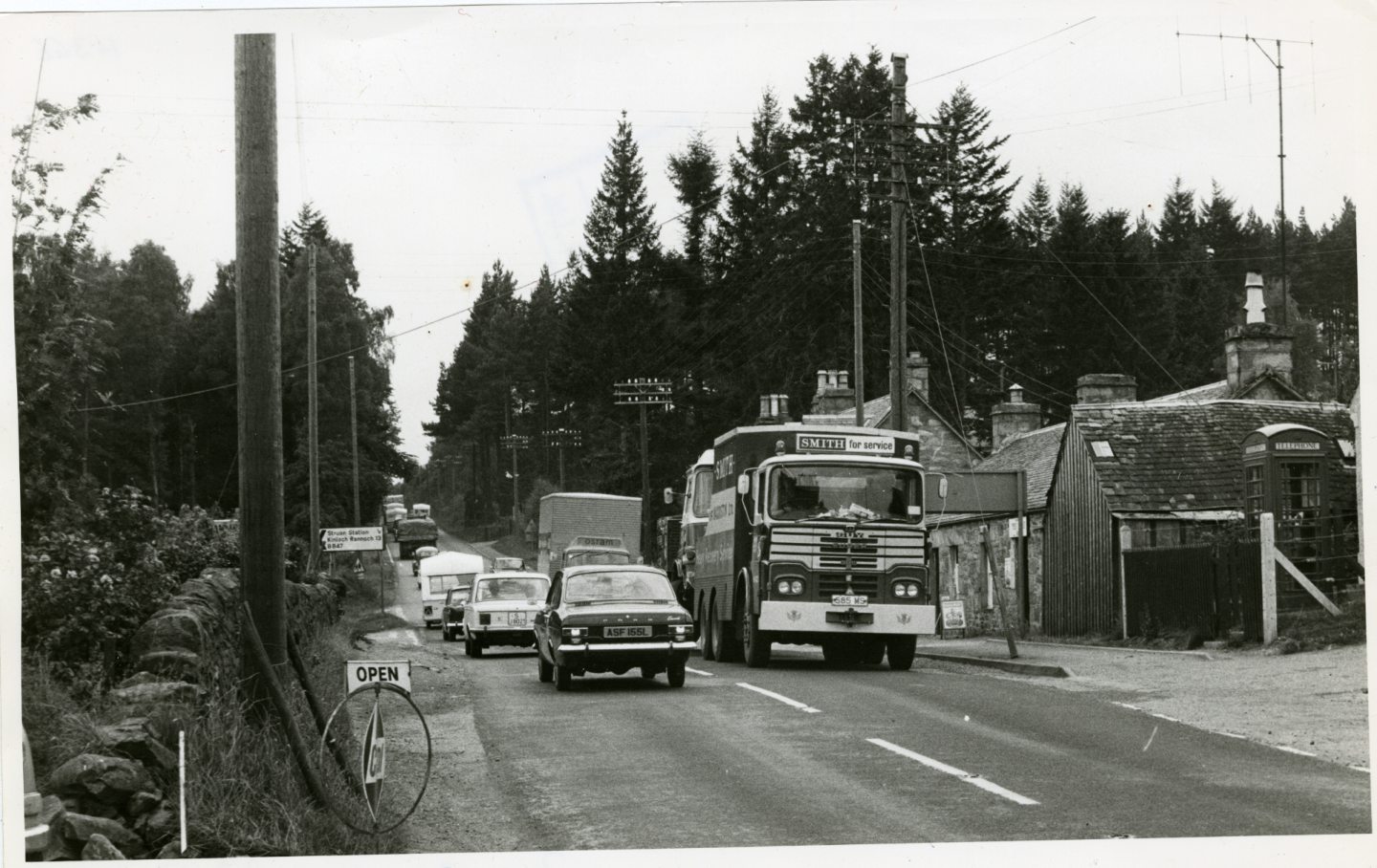

Oil boom accelerated upgrade

But the SDD ploughed on with the single-carriageway plans.

In 1974 it set up a special project team to speed up the A9 reconstruction “to meet new demands created by the oil boom”.

The immediate needs to service the oil industry took priority over long-term safety concerns.

The government said “an efficient trunk road network and adequate housing are infrastructure essentials for the oil programmes to go speedily ahead”.

A dual carriageway would take far longer to construct.

But the SDD added that the road would be built so an extra carriage-way would “be easy to add to any section as required in the future”.

‘A9 obsolete before it was built’

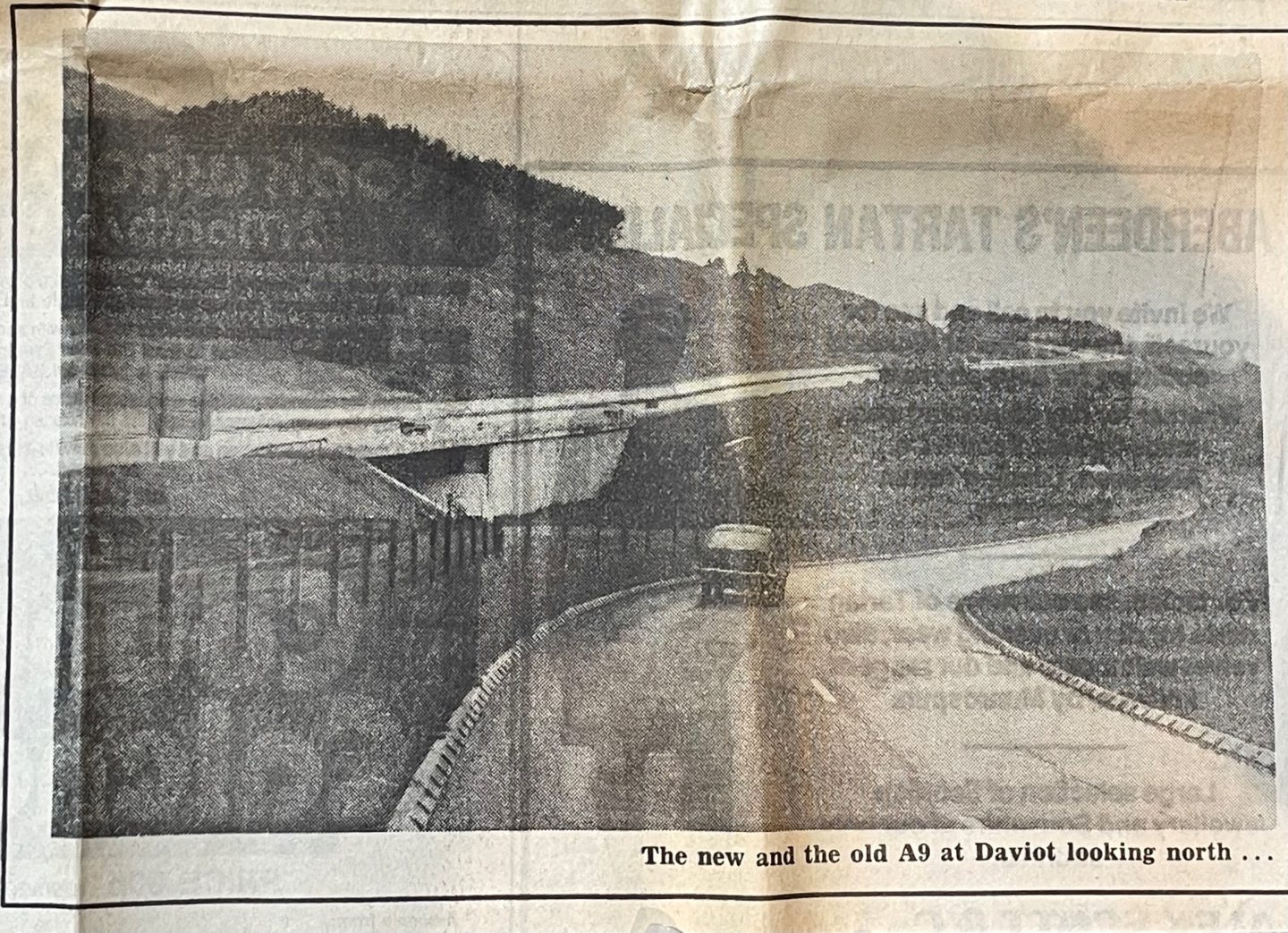

There was hope when the first 23 miles of the improved route opened in 1977.

Highland police initially reported a dramatic reduction in collisions at the Crubenmore blackspot.

But the commuters and communities who used the A9 were still concerned.

Even the workers building it in the 1970s knew it was inadequate.

Speaking to Radio Scotland last week, caller John said: “I worked on that A9 in the ’70s and the engineer at the time told me the road was obsolete before it was built.

“The traffic then was nothing like now.”

But in 1978, Garson Miller, the project superintendent for the A9 reconstruction, said dualling could “not be justified”.

He told the Scottish branch of the Institution of Municipal Engineers at a meeting in Dundee that there was no case for dualling “on the grounds of projected traffic volume”.

Instead just 25 miles of the 137-mile stretch would be dual carriageway at the cost of £130 million.

‘Who knows what another 60 years will bring?’

By the time the A9 was completed in 1982, costs had crept to £200m.

It was the longest new road to be built in Britain in the 20th Century and undoubtedly a feat of civil engineering.

Upon its completion, a documentary entitled ‘A9 Highland Highway’ was released by Films of Scotland.

Narrator Alec Heggie concludes: “This Highland highway will bring changes that we cannot even imagine.

“Who knows what another 60 years will bring, or take away, for the great road north is also the great road south.”

In some ways, it’s a haunting ending – because 50 years on, the road has taken away lives and brought grief.

Conversation