Calvin Ramsay’s meteoric rise up the football ladder resembles one of the storylines from the old Roy of the Rovers comics.

Just 15 months after making his senior debut for Aberdeen, the teenager has completed a £4.2million move to Liverpool and has been described in glowing terms by Jurgen Klopp, who has spoken of Ramsay’s “bags of potential” and enthused about how the Scot is “athletic, smart, confident, with good technical ability and – always crucial – is eager to learn”.

As usually happens in these cases, there will be plenty of expectations from the fans, but importantly, Klopp understands it will require patience for his new signing’s potential to be honed in the Anfield cauldron. In many respects, he is similar to Bill Shankly back in the 1960s: a paternal figure with a deep-rooted concern for his players’ welfare on and off the pitch.

So we’ll have to wait to discover whether Ramsay’s ferry to the Mersey earns some of the triumphant lustre or thoughts of what might have been which were the contrasting experiences of two other Aberdonians who travelled to the city just before Beatlemania took the world by storm.

He and Klopp would certainly be thrilled if his career trajectory came anywhere close to that of Ron Yeats, who served his apprenticeship as a slaughterman at Aberdeen Cattle Market before killing the dreams of so many opponents during his accolade-strewn years in the Liverpool engine room.

Yeats an intimidating presence

Yeats, a redoubtable figure who advanced from the Aberdeen Lads Club to become the first Liverpool captain to lift the FA Cup in 1965, was a colossus who commanded respect and there are plenty of stories about his grisly strength, not least the time when Shankly was so impressed with his new signing that he told a group of journalists: “The man is a mountain, go into the dressing room and walk around him”.

His intimidating presence after leaving Dundee United explained why he was installed as captain just six months after switching from Tannadice to Anfield in 1961 for a fee of around £20,000, and he soon took charge of affairs with a magisterial authority, which prompted Shankly to tell the press: “With him in defence, we could play Arthur Askey in goal!”

Rowdy, as he was known by the supporters, skippered his charges to their first league title in 17 years in 1963-64, but that was just a taste of things to come.

The following season proved one of the most momentous in the club’s history, and not just because it yielded their maiden FA Cup success with a memorable, but hard-fought 2-1 win over Leeds United.

Yeats subsequently led his team-mates on a journey into the unknown in their inaugural European match in Reykjavik. And, following victory in that tie, it was the tough-as-teak skipper who famously guessed right when Liverpool eliminated Cologne on the toss of a coin in a replayed quarter-final.

A different fate

The 1964-65 campaign also saw the club ditch its white shorts, and it was the talismanic Yeats who was chosen to model the new all-red kit. Shankly was convinced that the move would put the fear of God into any rivals – and if the sight of his centre-half in his pomp was anything to go by, he was right.

Yet, while he remains one of the Kop’s favourite sons, there was a different fate in store for another Granite City man, George Scott, who journeyed on a long and winding road from Torry to Liverpool and then Port Elizabeth.

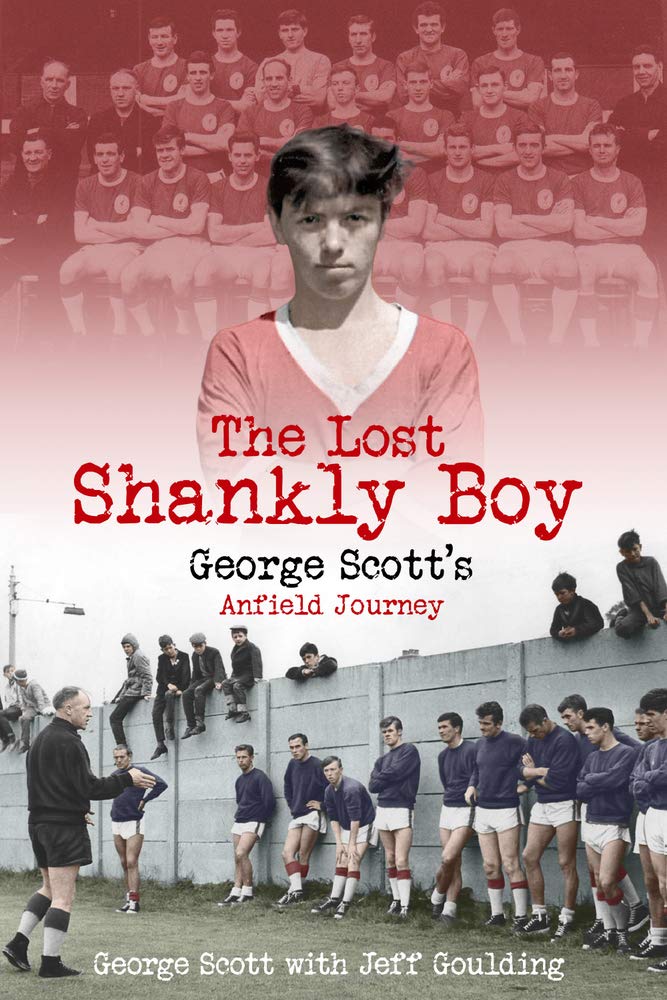

Even now, more than 60 years after he left his roots at 15, against his parents’ wishes, and ventured further than he had ever gone before to Merseyside, there’s a sprightly tone in his voice when he talks about his peripatetic life, which he has chronicled in his autobiography, The Lost Shankly Boy.

Scott clearly thought the world of Shankly and, amid the Swinging Sixties, that passion was reciprocated, even though the north-east player couldn’t quite break into the First XI in an age where there were no substitutes.

He said: “I was in the squad for the FA Cup final in 1965 and Shanks later described me as the 12th best player in the world.

“He had this aura which made you realise why he gained such an exalted reputation. You always felt his presence even before you saw him and he had a way of building you up”.

‘Sport can be cruel’

Sadly, though, Scott wasn’t destined for Liverpool greatness. Instead, he sustained a serious cruciate ligament injury in 1966 and was forced to completely re-assess his plans.

As he explained: “I felt really confident about my future, but sport can be cruel and when I suffered the cruciate injury, I was released at the end of the season in the summer of 1966”.

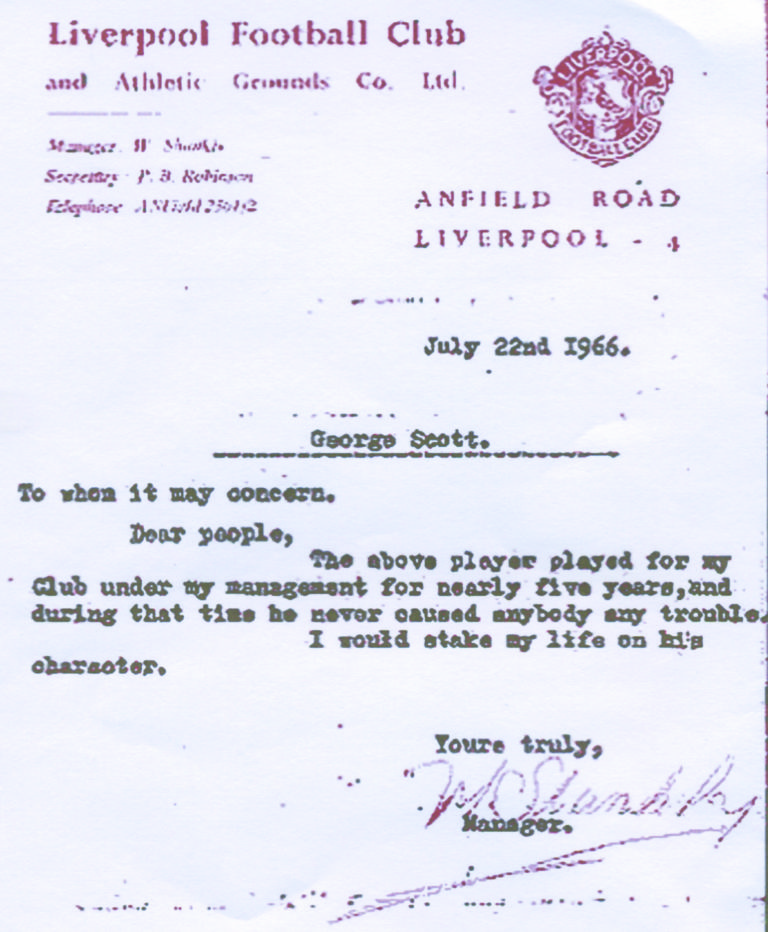

He was out of work at 21, having left school at 15, with nothing to fall back on and no qualifications. And though Shankly gave him a typewritten reference – “Dear people, George Scott played for my club under my management for nearly five years and, during that time, he never caused anybody any trouble. I would stake my life on his character” – the Anfield dream was shattered.

Football has advanced in myriad respects from these simpler times. It’s now a billion-pound global business.

But Yeats and Scott’s stories highlight how there is often a thin dividing line between adoration and adversity.