Folded carefully away in my parents’ West Highland home, when I was born there in May 1948, would have been one of the Ministry of Information leaflets delivered that spring to every UK household.

Printed on cheap and soon discolouring paper of the sort favoured by government in those years of post-war austerity, it bore an official crest and carried this heading in block capitals: THE NEW NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE.

“Your new National Health Service begins on 5th July,” ran the leaflet’s opening sentences. “What is it? How do you get it?”

Then came this introduction to what, in 1948, was a globally unique experiment.

“It will provide you with all medical, dental and nursing care. Everyone – rich or poor, man, woman or child – can use it or any part of it. There are no charges, except for a few special items.

“There are no insurance qualifications. But it is not a ‘charity’. You are all paying for it, mainly as taxpayers, and it will relieve your money worries in times of illness.”

Seventy-five years on, those words retain much of their power – not least because they speak to the existence in 1940s Britain of something that has largely gone from the Britain of 2023.

This something was a political willingness to take action of a sort that made it the moral and financial responsibility of the nation as a whole to help both families and individuals avoid or get out of difficulties they couldn’t possibly escape from on their own.

Not least among such difficulties back then were those arising from the misery caused by the onset of ill-health being compounded by ever-escalating doctor’s bills.

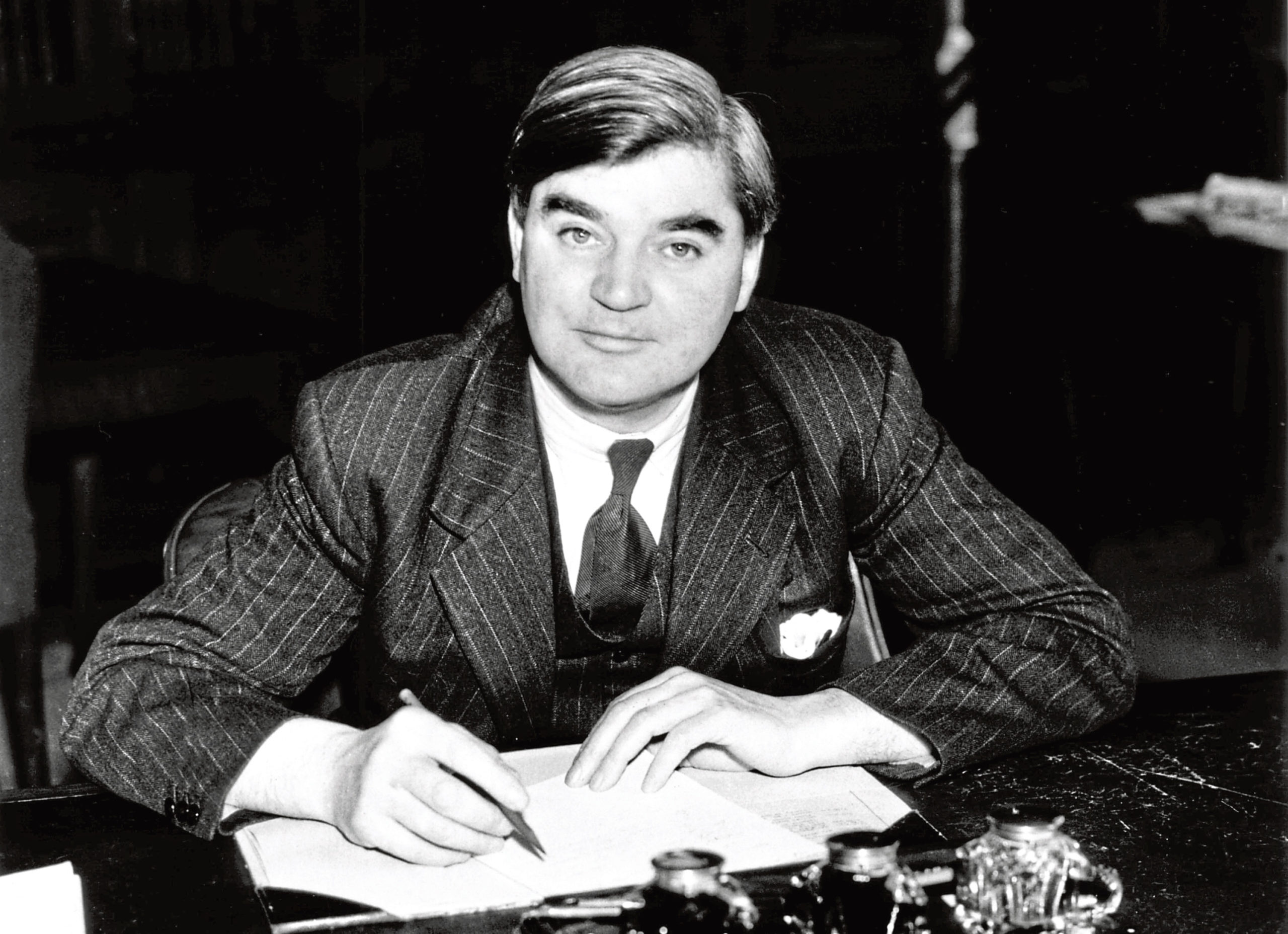

And, so, the Labour government elected by a landslide in 1945 (and, more especially, that government’s health secretary, Aneurin Bevan) set about ensuring that all of Britain’s people, irrespective of their financial circumstances, would be able to access medical care of a type that had previously been beyond the reach of lots of working families.

Embarking on a revolution to help the many

This was to embark on a revolution. And, like all revolutions, it provoked no end of opposition. From the Conservative Party. From much of the medical profession – a profession that feared the erosion both of its independence and its earning capacity. From local authorities, charities and other organisations previously in charge of hospitals about to be nationalised in order to standardise their services and to ensure that these services were available to everyone.

But eventually, by the summer of 1948, the job was done and the NHS brought into being.

“No society can legitimately call itself civilised,” Aneurin Bevan was to write of this achievement, “if a sick person is denied medical aid because of lack of means.”

Imagine what might be accomplished if thinking of this sort were to be applied to some of today’s most pressing social problems.

Suppose it were to be accepted that no society, ours included, can call itself civilised until all its people have adequate homes; all its children have access to free childcare and adequate nutrition; all its more elderly members are automatically assured of high-quality social care.

We’d be told – just as we’re told daily about the supposed impossibility of rescuing Bevan’s NHS from the various crises now engulfing it – that, while it would doubtless be nice to do these things, they’re sadly unaffordable.

But is that true? The NHS, it’s worth recalling, took shape in a Britain that was hugely poorer than the Britain of today – a country reeling from the immense costs incurred in the course of its then recently concluded war with Nazi Germany.

Today’s politicians should learn from Bevan’s example

So how, in the face of these grimly adverse circumstances, did Bevan and his colleagues set about making a reality of their vision of universally available healthcare?

By doing something that next to no mainstream politician is presently willing to do. By presiding over a tax regime designed to tap the wealth of richer segments of the population in ways that made a worthwhile proportion of this wealth available for purposes such as setting up the NHS.

Today, the 50 richest families in the UK have more wealth between them than the 33 million people constituting the less affluent half of the country’s population

There is plenty of scope for similar action in the Britain of 2023 – a country where inequality is now so acute that, as revealed earlier this month, the 50 richest families in the UK have more wealth between them than the 33 million people constituting the less affluent half of the country’s population.

So, when might a chunk of this wealth be accessed – by means of 1940s-style taxation – to enable today’s Britain to tackle housing shortages, sort out social care and get the embattled NHS into better shape?

Not any time soon, I fear. Which is a great pity. I won’t be seeing another 75 birthdays. But I’d like to think the NHS, though just six weeks my junior, might do exactly that.

Jim Hunter is a historian, award-winning author and Emeritus Professor of History at the University of the Highlands and Islands