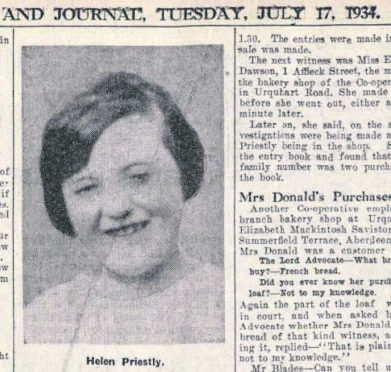

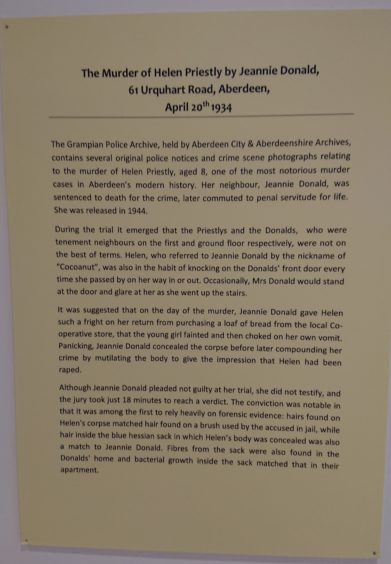

It was a crime which shocked Scotland to the core in the 1930s; the murder of eight-year-old Helen Priestly in Aberdeen by one of her neighbours in a crowded city tenement.

Even now, the death of the little girl, who went out to buy a loaf of bread for her mother and never returned home, remains one of the worst cases of a neighbourly dispute spiralling out of control and leaving destruction in its wake.

Helen lived with her parents, John and Agnes, in Urquhart Road, but her family were not on good terms with Jeannie and Alexander Donald, and, as the tragic events emerged of the circumstances which had led to her killing, it became clear that some childish name-calling has been the catalyst for the dreadful events which gradually unfolded on April 20, 1934 and in the next few days.

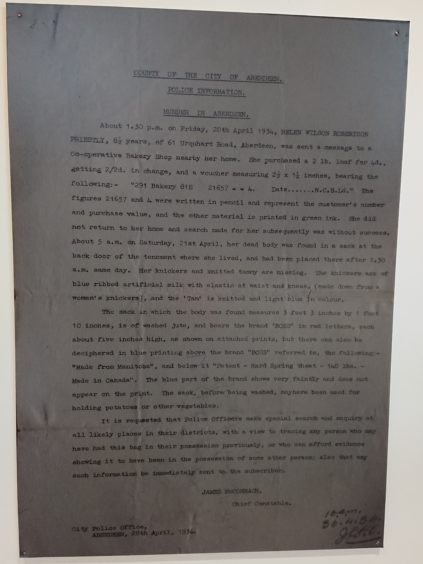

As the hours passed and Helen failed to return with the bread from the nearby Co-op store, the matter was reported to the police who subsequently launched one of the biggest-ever searches in Aberdeen.

Officers, assisted by volunteers from the surrounding area, continued to look for the missing girl throughout the night and into the early hours of April 21.

Yet, by this stage, as the Press and Journal reported at the time, the initial worry had changed to dread.

Ill-feeling between two families

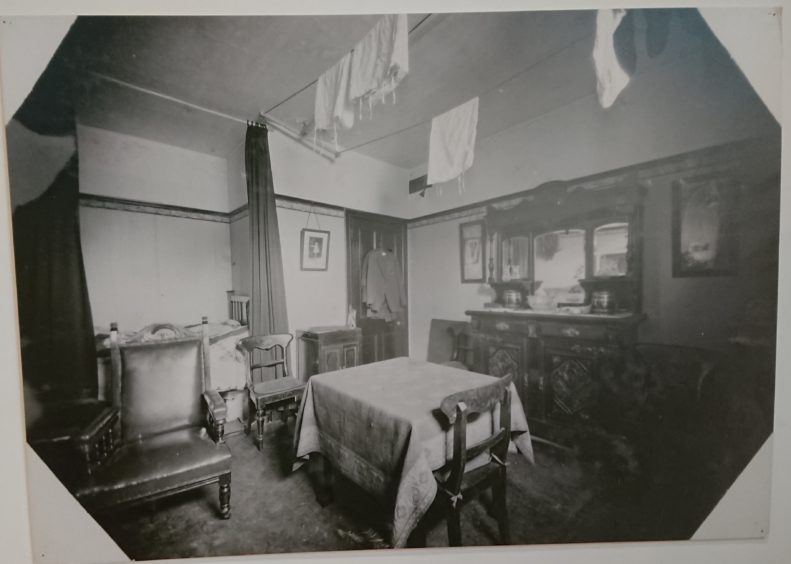

One of the neighbours, Alexander Parker, continued to look for her, but at 5am, as he was turning into the close to wake Mr Priestly, he discovered a blue hessian sack lying against the wall and, to his horror, was then confronted with Helen’s body.

An initial examination indicated the child had been strangled and also revealed bruising on her upper thighs and sexual organs and, as the news spread throughout the city, vigilante groups began taking to the streets, armed with clubs and other weapons.

The police recognised the volatility of the situation and the need to assuage public fears, and their investigations soon unearthed the ill-feeling which existed between the two families.

The Priestly family were popular with most people in the community, but they and the Donald family had exchanged harsh words and were not on speaking terms.

This was not uncommon in tenement life and there was no reason to suspect tragedy would ensue from Helen calling Mrs Donald a “coconut”, but a series of apparently petty incidents – a scowl here, a shake or a verbal insult there, eventually finishing in a slap – climaxed with a murder which gained banner headlines throughout Britain.

When the Donalds’ home was examined, stains were found and the couple were arrested, although these later turned out to be unconnected to the crime.

At first, both the husband and wife were implicated in Helen’s death, but the more the focus centred on Jeannie Donald – and details were released of how she had previously struck the victim – the forensic evidence became increasingly compelling.

Within a matter of days, human hairs were found in the sack and these were shown to belong to the 38-year-old accused, who was charged with murder and tried in Edinburgh on July 16, where she faced the full weight of the authorities, who had carried out a rigorous analysis of the crime scene and those involved in the tragedy.

There were many unanswered questions in the prelude to the trial.

By most accounts, Mrs Donald was a conscientious, hard-working woman with no history of criminality.

Her husband, a barber, who had initially been the prime suspect, was devoted to her and they had a daughter of their own, of Helen’s age, called Jeannie: was it possible this couple had conspired in such a dreadful offence against a small child?

And, if they had, why had they left the body so close to their own residence?

Not guilty plea at trial

Yet, once the trial commenced at Edinburgh High Court, in front of Lord Aitchison, the evidence was incontrovertible that the accused, despite her not guilty plea, had killed Helen and then attempted to make it look like a sexual assault.

Sir Sydney Smith, regius professor of forensic medicine at Edinburgh University, and Professor John Glaister of Glasgow University carried out meticulous examination of the crime scene and the samples of hair which had been unearthed in the hessian sack.

Prof Glaister proved that hairs found on the victim’s body matched samples discovered on a brush used by the accused in jail.

Other forensic investigators unearthed fibres from the sack in the Donalds’ home and demonstrated that bacterial growth inside the sack matched that in their house. Hour after hour, they inexorably turned the screw.

Worse still, from the accused’s perspective, Jeannie Donald Junior revealed that, on the day Helen had gone missing, she had noticed the bread in her home was different from the brand which her parents usually bought.

And it emerged the loaf she described was exactly the product which Helen had purchased on April 20.

This cumulative evidence was so conclusive that the jury took just 18 minutes to return a guilty verdict and Jeannie Donald became one of the first people in the world to be convicted on the type of forensic evidence which is nowadays taken for granted.

Outside the building, angry members of the public made their feelings plain and bayed for vengeance.

Yet, inside the court, Lord Aitchison, who had never worn the black cap before this case, was reduced to tears as he sentenced Donald to death.

After the verdict, which was covered in depth by all the national newspapers, she was driven off through the crowds in the journey from the Scottish capital to Craiginches Prison in Aberdeen to await her punishment.

On August 3, her lawyers lodged an appeal on her behalf, but contemporary accounts showed they were not hopeful it would succeed.

However, in the space of 24 hours, the Lord Provost of Aberdeen, Henry Alexander, had his summer holiday abruptly interrupted after receiving a letter from the Secretary of State.

This dramatic correspondence confirmed that the perpetrator would not face death by hanging, but instead be forced to serve “the rest of her life” behind bars at a women’s jail in Duke Street in Glasgow.

Model prisoner

Ultimately, though, despite the reprieve, the tragedy devastated two families. Donald never spoke about her reasons for committing murder, but she was later described as a “model prisoner”, somebody who adapted to an existence without her freedom.

Indeed, when Alexander Donald became terminally ill with cancer in the summer of 1944, she was granted compassionate leave to care for him in his dying days.

Then, in what many people regarded as a remarkable, if not inexplicable, development, the same woman who had been convicted of a capital offence was released from prison after her husband’s death – only 10 years after she stood in the dock with a haunted expression on her face as she heard the sentence.

Donald lived the rest of her life under an assumed name and died 32 years later in 1976 at the age of 81.

Helen’s parents, for their part, were denied any understanding of why their beloved daughter had been snatched away from them so young.

As one correspondent later wrote: “This was a case of a minor feud having catastrophic consequences for the families and Helen Priestly in particular.

“It was common enough for neighbours living so close together to have arguments and fall-outs.

”But, thankfully, these very rarely developed into anything worse.”

Gravestone restored

The memorial to Helen in the city’s Allenvale Cemetery was allowed to fall into disrepair and was in danger of disintegrating by the start of 2019.

But the gravestone was restored following a campaign by north-east crime historian, Bruce Collie, who was appalled at discovering the state of the burial site.

He initially contacted workers at the cemetery, but when nothing was done, he subsequently raised the matter with Aberdeen Bereavement Services.

Mr Collie, 58, said: “When I first came across Helen’s grave in 2016, it was shocking, because it was damaged, it was clearly deteriorating and it was just lying flat on the ground.

”I eventually got in touch with Ian Burnett at the bereavement services and, to his credit, he made sure the stone was cleaned and reset and brought back to a condition which pays proper respect to little Helen.

”Since it has been repaired, several people have placed flowers on the grave and that makes me very glad to think people are finally remembering this poor girl once again.”

It’s one of the few redeeming features in a dark chapter from Aberdeen’s past.