‘It’ll all be over by Christmas’. At least that’s what everyone wanted to believe when the First World War broke out in 1914.

By December that year, it was very much not over – and there was no sign of it being over.

But for many Gordon Highlander soldiers Christmas Day did bring respite from the fighting. If just for a few hours.

The Christmas truce, a much romanticised yet poignant moment in a long war, was a reality for many Scots soldiers, thanks to a compassionate Aberdeen chaplain.

The warring nations refused calls for a universal ceasefire, but in spite of this there were pockets of peace in unofficial truces along the Western Front.

Late on Christmas Eve 1914, the sound of gunfire and explosions faded away, replaced instead by the sound of carol singing drifting from the trenches.

‘Duty to serve men at front’

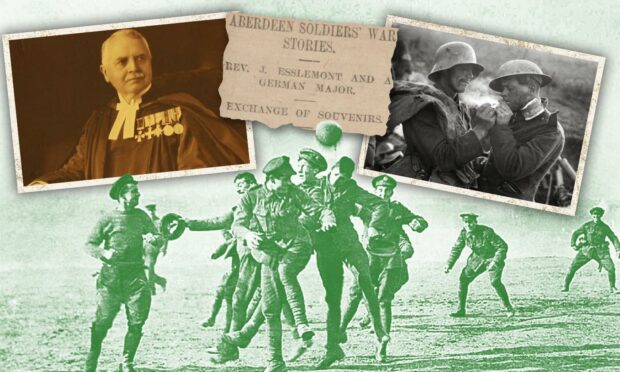

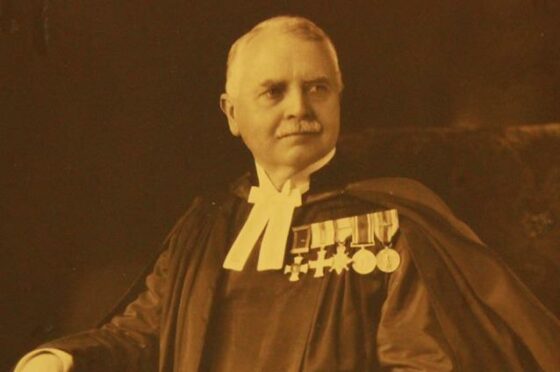

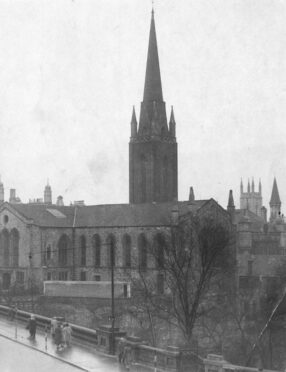

Reverend John Esslemont Adams, minister at the West United Free Church on Belmont Street in Aberdeen, was on the front line with the 6th Gordon Highlanders.

Born in Hamilton in 1865, Mr Esslemont Adams was an extremely intelligent man and accomplished academic.

He earned a host of qualifications from the University of Glasgow before finding his calling in the ministry.

Esslemont Adams then settled in Aberdeen with his wife Marion and daughter Mary.

When war broke out in 1914, he immediately volunteered to travel to the front with the Gordon Highlanders as chaplain.

He believed it was his “duty to serve the men at the front facing what he called ‘the stern reality of war’”.

A compassionate family man, Esslemont Adams comforted troops, and was a central figure in the unofficial Armistice of Christmas 1914.

Crossed no man’s land

After the quiet, calm of carols the night before, Esslemont Adams was conducting a burial on Christmas morning.

When he looked up, he saw soldiers on both sides laying down arms.

He told commanding officer Colonel Colin McLean that he wanted to approach the enemy to arrange the burial of men who had been lying dead in no man’s land.

Col McLean tried to stop him, but he crossed the wire towards the Germans and holding up his hands asked if anybody spoke English.

He was beckoned towards the German lines where a truce was arranged to allow both sides to bury their dead.

With weapons cast aside, what followed was a remarkable and heart-warming event.

Esslemont Adams and a German divinity student conducted a service, and the 23rd Psalm, The Lord Is My Shepherd, was read in English and German.

Scots soldiers offered their German counterparts chocolate, rum and cigarettes, and the foreigners reciprocated with wine, sausages, sweets and nuts.

Afterwards, Esslemont Adams was told he would either get a court-martial or a decoration.

It was the latter.

‘I wish it was all over’

The circumstances around the remarkable Christmas morning truce were captured in a letter sent home to Aberdeen by 6th Gordon Highlander, Private John Robb.

Prior to the war, Pte Robb had been employed on Aberdeen’s trams and he wrote to his manager to thank former colleagues for a care package they had sent.

In a letter dated ‘France, Christmas Day, 1914’, he said:

“This being Christmas Day, both the Germans and us ceased firing the whole day, and our chaps left their trenches and went over to the Germans and wished them a Merry Christmas.

“Our chaplain, the Rev J Esslemont Adams, went up to the firing line today, and had a talk with the Germans.

“One of the German majors gave him a cigar for a souvenir, and Mr Adams gave the major a small prayer out of his cap in return.

“He also read the burial service to 17 Germans who were buried today. The major told that they were quite fed-up and wanted to stop.

“We commenced fighting at 5pm again.

“I wish it was all over, as the trenches are not quite the best, but we are sticking it with a right heart.”

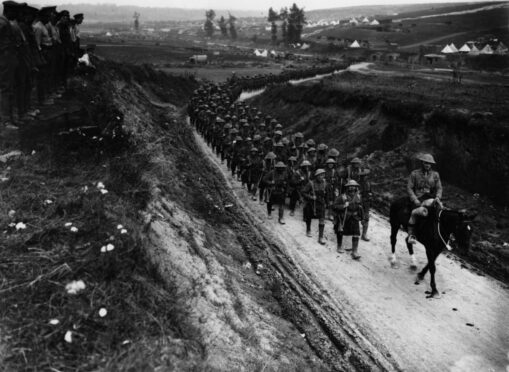

Gordons outnumbered

Other lulls in fighting were reported along the Western Front, but the impromptu peace didn’t last.

The British generals disapproved of the truce fearing it would affect fighting spirit.

They did not want the enemy seen as friends – or even as fellow human beings.

The magic of Christmas was soon over and the command was given to once again bear arms.

Pte Robb provided an insight into the relentless hostilities saying “our battalion is having a pretty hot time right now”.

He added: “We have lost a good many men. But we have to expect that.

“I have been very fortunate myself, thank God.

“Although I had a very narrow shave last Friday night, as we had a charge, but none of our chaps were touched.

“The Grenadier Guards and Gordons lost a lot of men that night. The Germans were about 30 to our 1, so we had no chance at all.

“We shall require a large amount of men out here yet to assist us, as we are outnumbered.

“We are four days and four nights in the trenches at a spell, and we are knee-deep in mud and water all the time.”

Letters to congregation

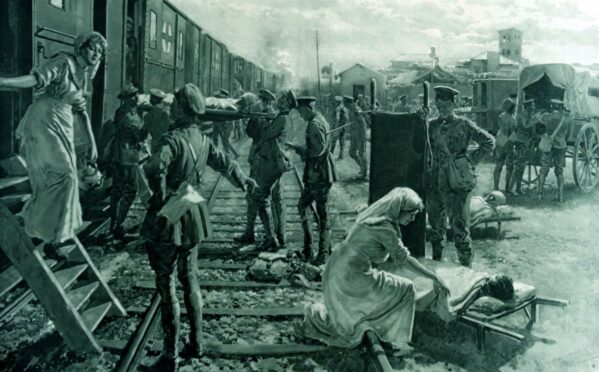

Esslemont Adams remained at the front throughout the war.

He often wrote home to his Aberdeen congregation of the strife and sacrifice he witnessed.

In 1916, he spoke of ambulance trains and how four hospital ships left a day, packed with sick and injured troops.

Many of whom were “Aberdeen men from regiments doing valiant things and suffering severely”.

And he lamented the loss of men from his own congregation back in Aberdeen.

In particular he was affected by the death of 21-year-old Lieutenant Frederick “Freddie” Conner who was “born and brought up” in his church.

He said: “To me personally his death is heartbreaking.

“Dear, gallant Freddie – one of the brightest, purest, most chivalrous boys in my friendship!

“I saw him often in warfare, and was justly proud of him.”

‘Buoyant and joyous spirit’

The kindly Aberdeen minister survived the conflict and earned a distinguished war record himself.

As well as commanding 60 chaplains at the front, he saw service in Egypt.

When he returned from Cairo in 1919, it was with a number of military awards.

He had been made a colonel and received the Distinguished Service Order, and was twice Mentioned in Dispatches.

And the King personally presented Esslemont Adams with a Military Cross.

Upon the minister’s death aged 69 in 1935, his daughter Mary reflected upon her father’s role in the famous truce.

She said: “There were many dead, both British and German, between the lines.

“My father longed to give them decent burial.

“He stood above the parapet of the trench, holding up his hands, and then began to walk towards the German lines.”

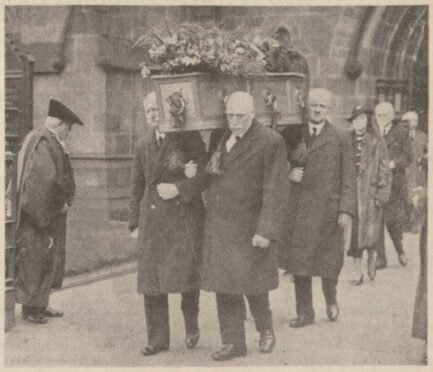

Esslemont Adams’ funeral was attended by hundreds.

He was remembered for his “large heart, his warm friendliness, his buoyant and joyous spirit, his constant kindness in thought and in deed”.

Poignantly, The Lord Is My Shepherd was sung – the psalm that brought Scots and German troops together in 1914.

If you enjoyed this, you might like: