It featured a lost world, a community that simply disappeared and a ferocious storm that sparked havoc in the Moray Firth.

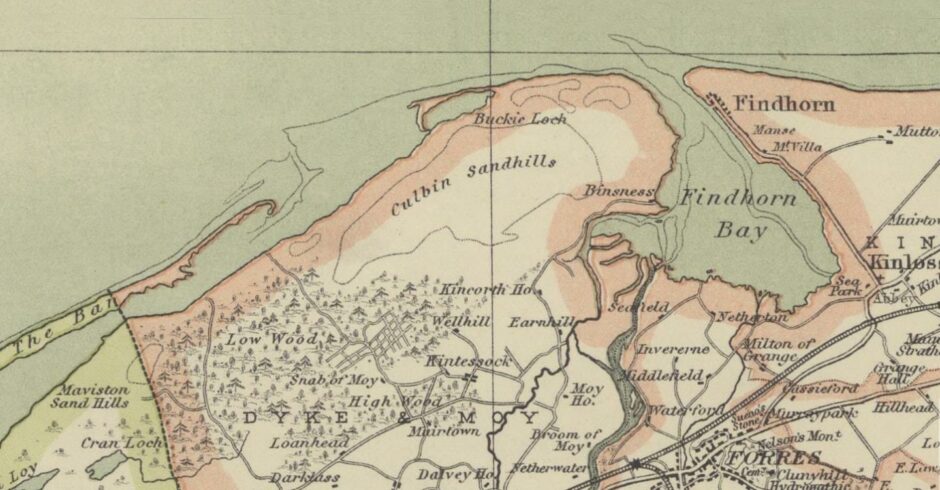

Yet such was the devastation wrought by the Great Sand Drift in 1694 that people in neighbouring settlements started talking about how the Devil himself or a ghostly figure called the Maid of Norway had been the catalyst for the dramatic events which led to Culbin’s destruction.

Even now, more than 325 years later, fantastical theories surround the grim fate that befell the village, which, according to some contemporary reports, vanished without a trace in a blizzard of sand and grit that enveloped everything in its path during a wind-lashed autumn.

It sounds like a worthy X File for Mulder and Scully and the two paranormal detectives would certainly have plenty of material on which to speculate.

Now, though, investigators closer to home are digging through the clues and striving to discover if the truth is out there in these giant dunes on the coast.

It’s still unclear whether the disaster happened in a single day or over weeks or months, but it had catastrophic consequences for residents in Culbin.

As one report from the time stated: “The Great Sand Drift was connected with changes in the coastline and the sand, which overwhelmed Culbin in 1694, (arrived) from the west. It came suddenly and with little warning.

“A man had to desert his plough in the middle of furrowing. The reapers in a field of late barley had to leave without completing their work.

“In hours, the plough and the barley were buried beneath sand. The drift came on steadily and ruthlessly, covering every object in a mantle.

A few decades after the great storm, a single farm was all that remained of those once broad and fertile acres of Culbin.”

An account of the disaster

“Everything which obstructed its progress quickly became the nucleus of a sand mound.

“In terrible gusts, the wind carried the sand amongst the dwelling houses, sparing neither the hut of the cottar, nor the mansion of the laird.

“The splendid orchard, the beautiful lawn, all shared the same fate. A lull in the storm occurred and they (the residents) began to think they might still have their dwelling places, though their lands were ruined for ever.

“But the storm came on with renewed violence and they had to flee for their lives, taking with them only such things as they could carry.”

It sounds dramatic enough. However, for those poor souls who departed Culbin in such terror-stricken haste, their nightmare was only just beginning.

As the account continued: “The sand choked the mouth of the river Findhorn, which now poured its flooded waters amongst the fields and homesteads, accumulating in pools until it rose to a height and was able to burst the barrier to the east and create a new outlet to the sea (the Moray Firth).

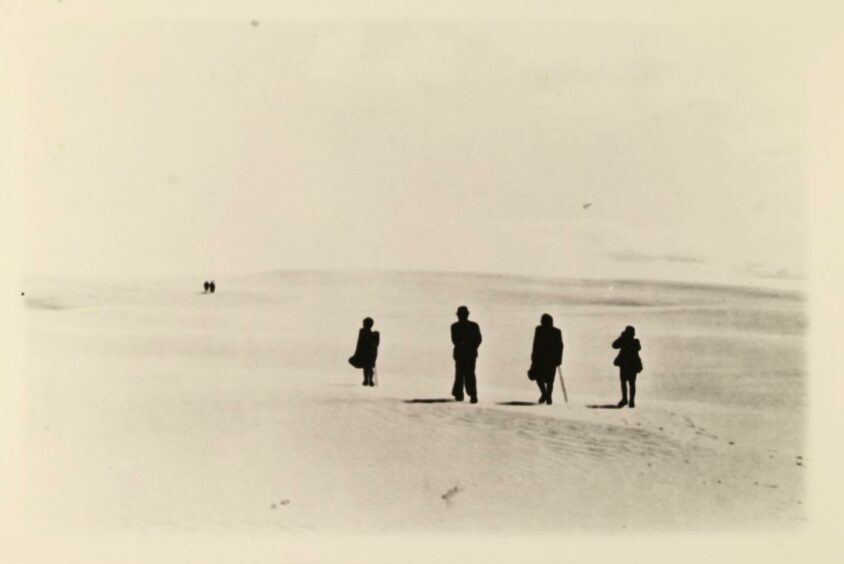

“On returning, the people of Culbin were spellbound. Not a vestige, not a trace of their houses was to be seen. Everything had disappeared beneath the sand.

“The scene which met their anxious gaze that morning was what we now behold – desolate and oppressive enough to us, but how terribly painful and harrowing it would have been to them.”

It must have been a horrific experience for these 17th Century Scots, caught up in something beyond their imagination, but while their village had been consumed by sand, sand, everywhere, a few still tried to defy the elements.

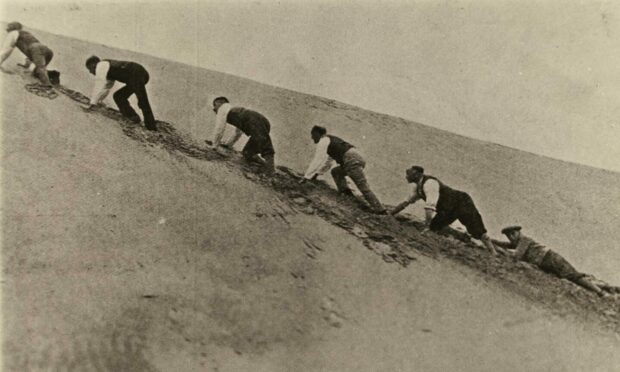

Even though it was in a lost cause, they knew nothing about such phenomena as coastal erosion, so they persevered in an increasingly futile battle.

But, as another report, one from the 19th Century, stated: “Sometimes a year or two would elapse without serious encroachment, and then would come a violent storm and, in a single night, many fields would be completely obliterated.

Culbin sand storm ‘divine retribution’

“Frequently, a field ploughed during the day would be buried during the night and, at the present day, one often sees in the valleys among the sandhills furrow(s) that were turned up more than 200 years ago.

“A few decades after the great storm, a single farm was all that remained of those once broad and fertile acres of Culbin.

“Of even that poor remnant, nothing now remains. The very names of the hamlets and holdings are as completely forgotten as if they had never existed.”

It was a dreadful scene of devastation. But, as those north-east people attempted to make sense of what had occurred, they started speculating about the cause of their ruination and found answers in various myths and legends.

One story centred on how the Laird of Culbin (Alexander Kinnaird) was guilty of breaking the Sabbath because he “was not content with the work of six days, but must have his people plough and bow and reap on the Sunday as well. The storm was divine retribution for his failure to keep the Lord’s Day”.

Another even more arcane suggestion was that the cataclysm was an act of revenge spirited up by the Maid of Norway, “who inherited the Scottish crown through her mother, but died in Orkney in 1290, aged seven”.

The legend continued: “According to superstition, she did not die, but was stolen by pirates from her father’s ship on the high seas and kept in confinement for long years by the Laird of Culbin, who figures as the villain.”

And so it transpired that she placed a curse on him and his land.

However, the most outlandish notion was that Kinnaird had forged a pact with the Devil to play cards even as his world crumbled all around him.

Improbable as it seems, this became a popular folk tale during the 18th and 19th centuries and Eliza Gordon-Cumming knew about it when she wrote a poem about the Culbin Sandhills and what might have happened there.

By the time she put pen to paper in the 1870s, this noblewoman had become the Hon Mrs Willoughby and was living in Yorkshire.

But she evocatively portrayed the arrangement between Kinnaird of Culbin and the Devil and how the pair had reputedly continued their game even while they were lodged in the heart of the largest mound of sand.

Whatever the minutiae of the events in Culbin, they are sufficiently striking to have become the subject of a new exhibition that examines and analyses the story as part of the Scotland’s Year of Stories project.

The event, which will be opened by the Earl of Moray on Saturday and runs from February 19 to March 16 at Elgin Library, aims to re-tell many of the stories of Culbin: The Disappeared Village in new and creative ways.

Dr Rachael Ironside and Professor Peter Reid from Robert Gordon University are the real-life Scully and Mulder in this particular file and, boosted by funding from VisitScotland and Museums and Galleries Scotland, they have poured themselves into the initiative with no little imagination or innovation.

Dr Ironside said: “The Disappeared Village exhibition explores how the lesser-told stories of Culbin can be reimagined through creative practice.

“Scotland’s People and Places will be celebrated by focusing on the community and heritage of the Moray Firth as well as the unique ecology of the Culbin Forest and Sands”.

Yet the question remains: what really happened to Culbin and how swiftly was this once-thriving settlement engulfed by sand?

Prof Reid told me: “The whole area of Culbin was definitely covered by the drift.

“However, I think there is evidence to suggest that the encroachment of the sand started earlier, in the mid 1670s and, bit by bit, it took over the land.

“But there is no doubt that, in the autumn of 1694, there was a long, persistent gale that engulfed the village, though not perhaps in one night as legend has it.

“I think that geographers and meteorologists have proved that the quantity of sand couldn’t have been blown in a single night.

“But that big storm was the final, cataclysmic end for the village”.

Spooky, eh? And pause for thought in our own storm-tossed winter!

- Further information is available at visitscotland.org/news/2021/yos-events