The name Nobel is, in the minds of millions, instantly linked to the word Prize – winning a Nobel Prize is seen worldwide as the highest accolade a scientist, medical researcher, author or economist can aspire to.

The winners are announced every year in Stockholm and Oslo – this year between October 3-10 – and, despite one-time allegations of internal politics, Nobel Prizes generally carry a repute and prestige unmatched by any others.

Yet the origins of the prizes once caused deep concern to many. They were the brainchild of Alfred Nobel, a Swede who became one of the world’s richest men thanks to the most famous of his countless inventions – dynamite.

As with many scientific discoveries, from smelting iron to atomic power, dynamite’s benefits (it hugely improved mining, quarrying, tunnelling and civil engineering) have all too often been eclipsed by the use of subsequent explosives in warfare.

Astonishingly, for years Nobel’s biggest explosives plant was in Scotland, on the Ardeer peninsula in Ayrshire. At its height it employed 13,000 people on-site and many more in its supply chain. Indeed, Skye’s only railway line was built to provide Ardeer with the crucial mineral diatomite.

For decades, too, another important Scottish source of supply was Black Moss, at the Muir of Dinnet, a mile or so north of the village in Royal Deeside, which operated from the 1860s until the end of the First World War and possibly later.

Talented family

The Nobels were a talented family. Their father Immanuel was an engineer who devised and patented a series of inventions, including an early machine to make wood veneers and plywood.

Alfred was the third son and one of eight children, four of whom died young, but the four surviving brothers all did well, Alfred best of all. He combined determination and inventiveness with business acumen and became fluent in five languages in addition to his mother tongue.

He studied in several countries and later had residences all over Europe, including Scotland. For a long time in later life his main residence was in Paris, but an extraordinary circumstance meant he had to leave France in a hurry.

One of his many inventions was Ballistite, a then powerful propellant for bullets and shells. In the mid-1880s Nobel had offered Ballistite to the French government, but they refused, opting for a chemical devised by a French scientist.

However, Italy decided to use Ballistite and Nobel opened a factory in Turin to make it.

This appalled the French government, who accused him of treason. So he had to up sticks and move to San Remo in Italy, where he died aged 63 in 1896.

Explosive discovery

This 19th Century proliferation of different explosives followed centuries when the one known explosive was gunpowder – a mix of carbon, sulphur and potassium nitrate. It was usable, but by modern norms it was feeble, hard to keep dry and, once damp, often failed to ignite and explode.

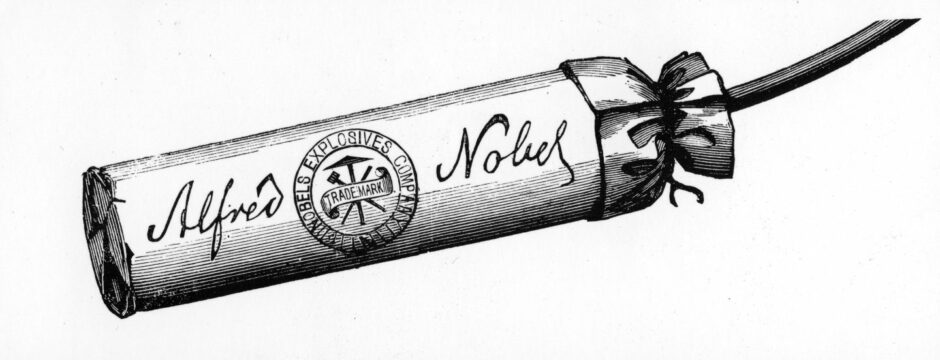

Then In 1840, Italian Ascanio Sobrero invented nitro-glycerine, a powerful liquid explosive but highly unstable – just knocking a beaker of it could make it detonate.

Alfred and his brother Emil sought ways to make it more stable. It was dangerous work – Emil and several colleagues were killed when one experiment went badly wrong.

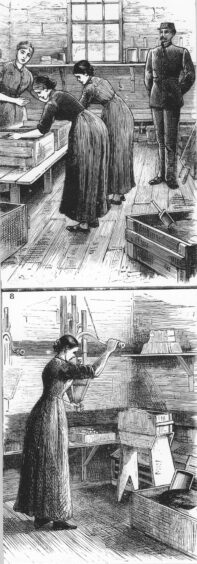

Despite such setbacks, Alfred persisted and finally found that soaking nitro-glycerine into kieselguhr or diatomite (a chalky white porous substance – actually, micro-skeletons of pre-historic algae) and shaping the mix into sticks sheathed in red paper, allowed it to be used relatively safely.

Dynamite was not hazard-free but, handled correctly, was widely used and a huge success. Almost all “conventional” explosives developed since by Nobel and others – Gelignite, Amatol, RDX, TNT, guncotton, Ballistite, Semtex – are one way or another derivatives of dynamite or its basic concept.

The Nobel Prize

When Nobel died in 1896, he reputedly held 355 patents and owned, or was involved with, 90 companies, many involved in armaments and munitions.

Indeed, when his brother Ludwig died, one French newspaper, wrongly assuming it was Alfred, headlined, “Le marchand de la mort est mort” – The merchant of death is dead.

That shocked Alfred deeply and it is said he proposed the Nobel Prizes, and bequeathed most of his fortune to fund them, as a gesture of contrition.

After his death in Italy, his body was brought back to Sweden and he is buried in a graveyard just north of Stockholm.

The demand for Nobel explosives saw factories set up in many countries, especially those such as Germany, with big armies and navies. Nobel was especially keen to establish a factory in Britain but the UK Parliament, alarmed by several bad accidents with nitro-glycerine (one consignment imported through Liverpool blew up in Caernarvon in 1869), had banned nitro-glycerine and explosives containing it – which long thwarted Nobel’s UK ambitions.

However, in 1871 Nobel Industries Scotland was established by a group of Scots businessmen including John Downie, the head of Fairfield Engineering and Shipbuilding in Glasgow, and who became the company’s first MD.

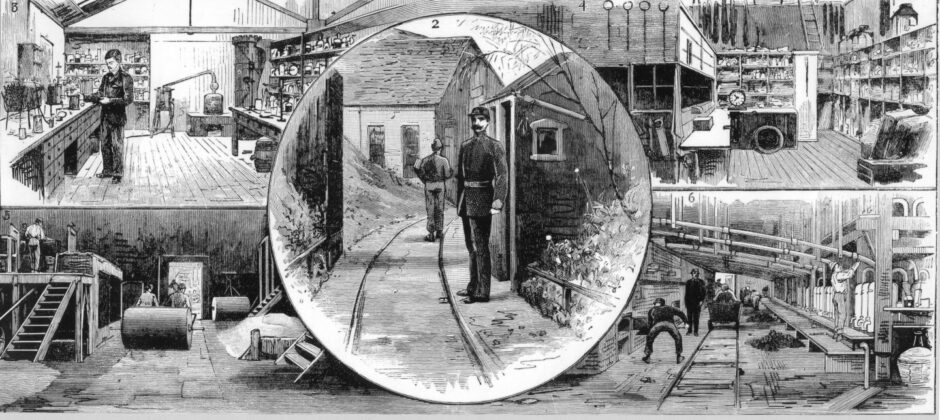

A factory was built on the Ardeer peninsula between Stevenston and Irvine.

Scottish roots

Back then, Ardeer was a windswept wilderness of sand dunes and coarse grass. But over the coming years the initial factory grew to an immense complex with internal road and narrow-gauge rail networks and its own jetty on the River Garnock estuary, both for ships bringing diatomite from Skye and those exporting explosives overseas.

The complex even had its own marshalling yards and a passenger rail station for the 13,000-strong workforce that commuted to Ardeer daily from across the west of Scotland.

It eventually claimed to be the world’s largest explosives factory, exporting countless tons of explosives across the planet.

Bitter experience had taught Nobel not to build one vast factory but rather smaller dispersed units so, if one blew up, the others would be unaffected. Hence the Ardeer complex was built on that principle, with sand being heaped into large mounds around each unit so any blast would be absorbed or deflected upwards.

Ardeer needed large quantities of kieselguhr/diatomite, and a big deposit was found at the tiny Loch Cuithir on Skye, some miles inland and just north of the Old Man of Storr. So a narrow-gauge railway was built to bring the wet diatomite down a steep incline to Invertote on Skye’s east coast where it was dried and treated in a large plant, then shipped to Ardeer.

The railway operated for many years from the 1880s onwards and it remains the only rail line ever built on Skye. Faint vestiges of the line and the treatment plant can still be seen today, but the jetty where ships were loaded has almost totally vanished.

Evolution of Nobel business

In 1927 Nobel Industries Scotland merged with three other big chemical firms, Brunner Mond and Co, the United Alkali Company and British Dyestuffs Corporation, to form Imperial Chemical Industries, or ICI, which became one of Britain’s biggest and most powerful firms, involved in manufacturing everything from paint to pesticides to pharmaceuticals.

The Ardeer complex was renamed ICI Nobel. It continued to operate until the 1960s, although the workforce dwindled over the years, then for 12 years it became a nylon and nitric acid plant.

In 2002 it was sold to the Japanese firm Inabata, a trading subsidiary of Sumitomo. It was in the headlines in 2007 after a bad fire destroyed more than 1,500 tons of outside-stored nitrocellulose – but there were no casualties and relatively little damage.

Today at Ardeer some 300 employees still make explosives, now euphemistically called “energetics”, for the Scottish division of the Chemring Group. However, the heydays of the peninsula are gone and the former rail station is completely overgrown.

Diatomite has many industrial uses other than making explosives. It has been used for filtering beer, whisky and other drinks, to make safety matches and is added to paper and plastics as well as toothpastes, abrasive cleaners and polishes.

Rising demand saw the diatomite operation at Loch Cuithir revived in 1950. However, with the rail line to Invertote dismantled, the mineral was instead taken by road to a treatment plant at Uig before shipment to various UK customers including ICI.

Sadly, the operation folded in the early 1960s, putting about 30 men out of work.

However, a farm track, possibly the bed of the old rail line, runs from the A855 north of Portree to Loch Cuithir.

And who knows, maybe one day a new boom demand could see Skye’s forgotten diatomite industry revived again. Perhaps even Dinnet?

Conversation