ScotWays, the oldest outdoors access group in the world, is marking its 175th anniversary. Gayle Ritchie looks at some of the charity’s most famous historic battles and explores why rights of way are just as important in 2020 as they were in 1845.

Ever been confronted with a “private” sign, a padlocked gate or a field full of cattle on a route you believed you had a right to use?

For centuries, there have been challenges, legal battles and public protests over where people can roam freely.

In the mid 1800s, landowners in Scotland were becoming increasingly jealous of their possessions and ordinary folk were being prevented from walking in the countryside. This incited a great deal of fury and sense of injustice.

Ill-feeling over roads around Edinburgh being blocked in 1845 led to a motion being passed which called for a right of access to the countryside.

Shortly after, the Association for the Protection of Public Rights of Roadway in and around Edinburgh was formed, and within two years it was involved in one of the most celebrated cases in the history of access in Scotland.

The Battle of Glen Tilt

Edinburgh botanist John Balfour took a group of students on an excursion to Glen Tilt in August 1847, whereupon they encountered the Duke of Athole and his ghillies barring the way.

An acrimonious encounter about the disputed right of way ended only when Balfour and his students climbed over a dyke and ran off down the glen, taking refuge in a Blair Atholl inn.

The lengthy lawsuit which followed vindicated the right of way through Glen Tilt, and also established the Association’s role as defender of the public’s interests in such cases.

Jock’s Road

Forty years later, the Association, by then renamed the Scottish Rights of Way and Recreation Society, became involved in another famous legal battle.

A party from the Society led by Walter Smith set out on an expedition through the Cairngorms to signpost rights of way.

This was intercepted at Glen Doll by the nephew and gamekeeper of the landowner, Duncan Macpherson, and the subsequent lawsuit was only finally settled in the House of Lords.

The ruling confirmed the status of Jock’s Road as a right of way, but it left both the Society and Macpherson virtually bankrupt, such was the cost of litigation.

The Lion’s Face: Burning of the barrier

An historic clash over the erection of a fence along a pathway past the Lion’s Face (a rock feature) was put into verse by an unknown poet.

It told of how a group of people trooped out onto Invercauld Estate in Deeside “with glee” to see “the noxious barrier fall”.

A “man of law” was said to have sawn down the fence and then set it alight, proclaiming: “The barrier is on fire!”

The wall

The Darn Road near Dunblane was an ancient trackway that local tradition says was used by the Romans.

By 1858 the diversion of the “Darring Road”, as it was known, caused much local upset.

John Stirling of Kippendavie closed the road by having a wall built across it, but each night the day’s work was knocked down, allegedly by the same workmen who had been tasked with erecting it.

Robert Louis Stevenson regularly used the Darn Walk. Suggestions have been made that a cave along it was the inspiration for Ben Gunn’s cave in Treasure Island.

Lost rights of way

Since 1945, many rights of way have been lost under densely planted forests and the rising waters of hydroelectric reservoirs, and promises to reinstate paths remain unfulfilled.

There’s also been a continuous gradual erosion of rights of way due to changing agricultural practices, building developments and the influx into Scotland of landowners who have no knowledge or respect for traditions of access.

However, there can be no doubt that but for the work of the Society, now named ScotWays, the loss of rights would have been greater.

What is a right of way?

In Scotland, a right of way is a route over which members of the public have been able to pass unhindered for at least 20 years.

The route must link two “public places”, such as villages, churches or roads and can sometimes involve going through private property. And this is where tempers can flare and disputes can rear their ugly heads.

Pathway of the pioneers

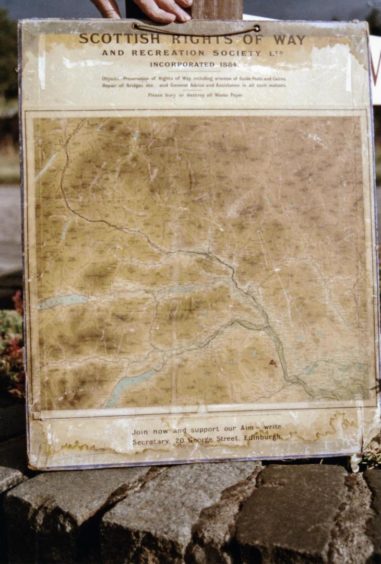

Since 1845, ScotWays has defended and asserted the public’s right of access to paths and land through signposting, court cases and negotiation.

“We’ve taught people about the heritage of paths, explained about the country’s access laws and the development of peoples’ rights of access,” says Richard Barron, chief operating officer.

“We’ve created guidebooks, leaflets and law guides. We developed the world’s first digital database of rights of way. Where we have lead, many have followed.”

It’s important to keep on using rights of way, says Richard, because if they’re not used, we risk losing them.

“Unlike the rights of responsible access to land, rights of way are created through continued usage for at least 20 years,” he says.

“So when you use a right of way, you really are following in the footsteps of the past.”

“Rights of way allow you to get through areas where the public right of responsible access doesn’t apply and they connect you with history.”

Happy birthday!

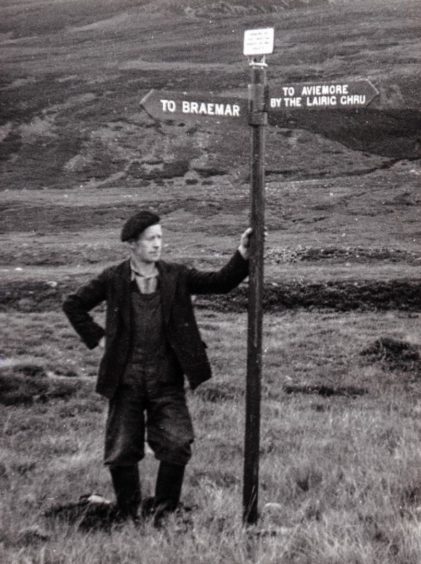

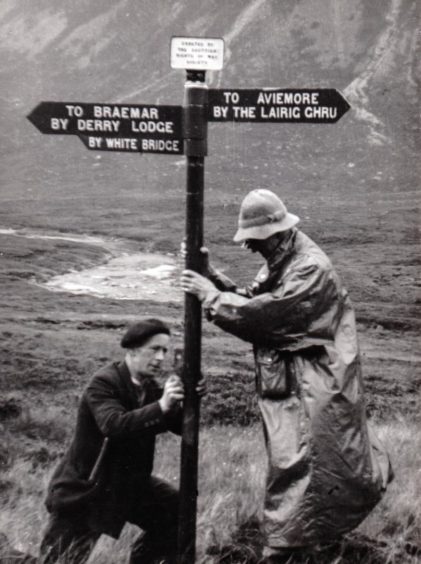

As ScotWays marks its 175th anniversary this year, the society revisits the scenes of its triumphs and clashes and invites people on a virtual celebratory journey – following in the footsteps of its pioneers as they installed the very first signposts across the Cairngorms in July 1885.

The director of the society at the time, a Victorian gentleman named Walter Smith, led the groundbreaking, week-long signposting mission, starting in Forfar and finishing in Blair Atholl.

The intrepid team covered 200km via a combination of rail travel, horse and cart, and good old walking.

Walter led them through Glen Doll, across the Tolmounth via Jock’s Road, and wrote up a detailed report of the expedition.

You can join ScotWays (virtually) along this historic route as part of your daily exercise, discovering the area’s history and heritage as you take part in the charity’s 175th Anniversary Challenge.

Whether you walk, jog, cycle, horse ride, canoe or even swim, the aim is to move 206km over 86 days around your local area and track your progress online along the route taken by Walter and his team.

“On the website, you can see a map of the route travelled by Walter, with markers for you and other challengers progressing along the route as you rack up distance from your daily exercise,” explains Richard.

“You can even use Google Street View to look around the real route through the hills, including through the Lairig Ghru.”

Using Walter’s original walk report, broadcaster James Naughtie will retrace the society’s 1885 expedition through Angus and into the Central Highlands.

The daily updates will include information about events that took place along the route, including aircraft crashes and the Cairngorms Plateau disaster of 1971.

The challenge will be open for 86 days, so you don’t have to try to do the whole thing in a week like the original ScotWays group!

It kicks off from 9am tomorrow (July 18) and will be available online at www.scotways.com

To join, people are being asked to make a donation to ScotWays. You can find sponsors and attempt to raise £175 if you wish – a fitting way to mark a 175th anniversary!

Everyone who completes the virtual route will receive a virtual certificate and a real medal in the post.

Here’s a flavour of what to expect…

Day one: The party arrive at Forfar railway station.

Walter said: “Besides the regulation knapsack carried by each, one of them emerged from the train with a large thin package which he bore up with difficulty.

“Its disposal exercised the minds of the party, who were joined here by a friendly barrister native to these parts and, carrying the mysterious parcel by turns, the deputation entered the ancient town of Forfar.

“Stopping at a close leading off the High Street, they accosted a burly smith who was gazing at the continental looking group of market people selling pigs, fruit, and all sorts of produce around the town hall.

“When the brown paper was removed from the parcel at the smithy door, it turned out to be a sign indicating in red letters on a dark background: Public Path to Braemar.

“The smith being instructed to prepare the bolts required to attach the sign to a guide-post, which had been ordered to be in readiness at Clova, the deputation shortly, drove off to Cortachy, nine miles distant.

“The high road leads through a sandy moorland country exhaling then a most delicious fragrance of clover, with the blue Grampians looming through the mist in the distance, and fords that pleasant trouting stream, the Prosen, near its junction with the Quharity and the South Esk, where the ruins of Inverquharity Castle are seen peering above the trees.

“Here, also, the beautiful grounds of Cortachy Castle, the modern residence of the Earl of Airlie, were visited and admired.”

The deputation lunched at the “unpretentious inn” at Dykehead of Cortachy, and then set off on their 12 mile walk up Glen Clova.

Day three: The first signpost was installed, asserting an ancient right of way and following the historic route of Jock’s Road.

The estate of Glen Doll had been purchased by Duncan Macpherson two years prior to the group heading out on its mission.

Walter said Macpherson “seems to attach undue importance to the occasional transit of a pedestrian”.

Prior to Macpherson’s arrival, the majority of sheep drovers and wayfaring people, travelling to and from Braemar and Forfarshire, were allowed an undisturbed passage through Glen Doll and Glen Callater.

There was just one incident in which a traveller though Glen Doll had been “seriously challenged”.

Walter recalled how an informant told him: “The late Miss Macgregor, tenant of the farm of Auchallater near Braemar, who had for half a century paid an annual visit to Clova on business and other matters, and whose flocks of sheep had regularly been sent to the Kirriemuir sheep market, was on one occasion interrupted by ghillies, and ordered to go back the way she came.

“She at once demanded to be taken to the lessee of the shootings, to whom she intimated that unless a full apology was given she would immediately adopt legal proceedings. The full apology was made.

“She was most handsomely treated to all the dainties a shooting lodge could afford, and a ghillie was sent to lead her pony all the way to Clova. This incident virtually settled the point at the time, and afterwards I never heard of a case of interruption of Jock’s Road.”

When the group, having informed Mr Macpherson of their mission, arrived at a wooden bridge across the River Esk leading to Glen Doll, his nephew and a gamekeeper were “in attendance”.

There was already a guide-post in place stating “Private Entrance to Glen Doll”.

But the society’s post, “Public Path to Braemar” with its signs pointing up Glen Doll, was duly erected.

Walter said: “In the company of young Mr Macpherson and the gamekeeper, the deputation crossed the bridge and continued to walk up Glen Doll. Both were courteous, and the gamekeeper pleaded the laird’s case as skilfully as any advocate could have done.

“He pointed out that, wherever the old road had gone, it was not up his master’s avenue, and when the wish was expressed to avoid any intrusion and take the old path, he said it was not his business to point it out.

“In point of fact, the old drove road kept up the bank of the Esk and along the boundary wall, but Mr Macpherson has planted over this part of the old road, and so effectually closed it, and therefore only one possible passage is left at present, which passes round the back of the lodge. The gamekeeper, however, did his duty here.

“He ran to the front and called a halt, and when he objected to the deputation proceeding further, he was referred to the society, whose prospectus had previously been handed to the nephew.”

The gamekeeper backed down and the party progressed up the glen until they came to a deer fence with a padlocked iron gate across the path. The group was forced to squeeze through the wires.

The gamekeeper continued to accompany the party, to “see what track they would take”, despite the fact the path was very obvious.

Soon, stunning Loch Callater came into view.

“That such a road as this should be lost to the public would be a most grievous misfortune; and such misfortune it is the object of this Society to prevent and retrieve,” concluded Walter.

Day six: This was spent around Rothiemurchus, signposting the northern end of the Lairig Ghru.

Sir John Grant and his shooting tenants were said to have objected to a sign being erected at a gate into a forest at the north end of Loch an Eilein

Walter said: “The gate is now kept locked during the summer and autumn and the good woman at the cottage near at hand faithfully refuses to produce the key.

“Great local irritation is felt at this iron-bound obstruction to an old-established road, and to regular visitors to Speyside it is a harsh and high-handed interference with their wonted quiet, and as they consider perfectly legal, enjoyment of the beauties of this lovely country.

“The Lairig Ghru Pass is as old as the Cairngorm Mountains themselves and yet, if locked gates are put on the roads leading to that pass, how is one to get up to it?

“The guideposts erected by the society are a first step at any rate towards answering that question.”

Trailblazers

While the party’s mission had been completed, the experience made them aware that a great deal more needed to be done, if routes were to be retained for public use.

Examples of inconsiderate landowners trying to shut out the public from old roads were in abundance.

Walter said: “These paths should become as well known as the turnpike roads of the country. They should be used regularly, and pedestrians using them should feel that they do so by right and not by favour.”

Plans were drawn up to have them marked on a map, with roads examined and measured so legal disputes could be avoided.

Certainly, the 1800s were an important period in the history of ScotWays.

Much that these intrepid directors did marked the beginnings of actions that continue today.

“These paths should become as well known as the turnpike roads of the country. They should be used regularly, and pedestrians using them should feel that they do so by right and not by favour.”

Signing rights of way continues to be a major part of ScotWays’ operation and today there are more than 3,500 rights of way signs across Scotland although the designs have changed.

The old green signs with white lettering are the most visible reminder of the charity’s activities.