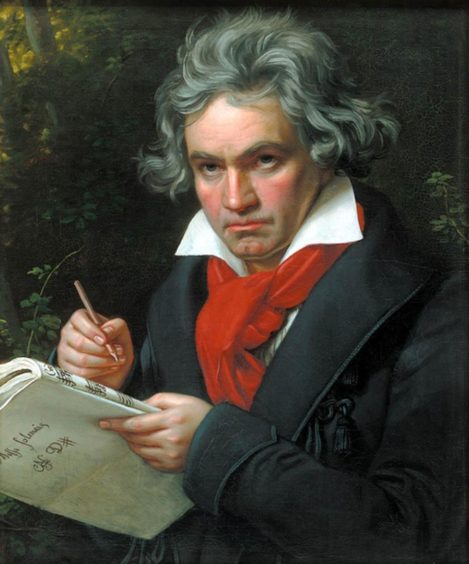

He is one of the world’s most famous composers – and Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Germany 250 years ago this month.

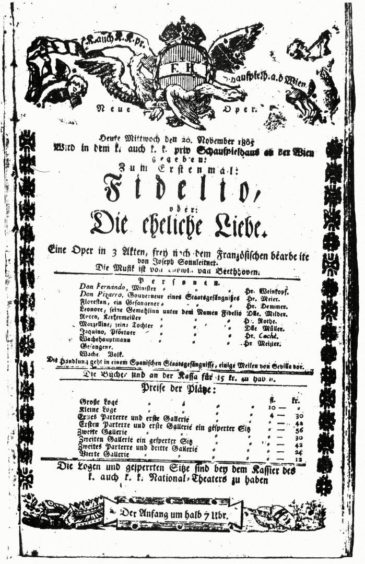

As the creator of such works as the Pastoral and Eroica symphonies, the opera Fidelio, the Moonlight Sonata and Ode to Joy, time has not diminished the impact of his work or its popularity throughout the world.

Yet, while the anniversary is being commemorated with many different events, albeit with social distancing, few people will be aware of the links which Beethoven had to many poignant and evocative Gaelic songs – or the fashion in which he joined forces with acclaimed author and poet Sir Walter Scott on a number of projects.

However, a new documentary, which will be screened later this month, has revealed that he made classical arrangements of many traditional Gaelic songs – although the often tragic or political lyrics of these works were never revealed to him.

Smuggling ship carried Beethoven letters

The celebrated composer created new versions of 47 Scottish melodies from 1809 to 1820 for the Edinburgh-based folklore collector and publisher George Thomson.

The two men remained in regular contact through a series of letters, written mainly in French, which often took weeks or months to reach their destination and, on one occasion, it’s believed the correspondence was only maintained with the help of a smugglers’ ship via Folkestone.

But while Beethoven was entranced by the ballads which originated in South Uist and the rest of the Western Isles, he was not aware that Thomson had ensured the lyrics and titles of the songs had been amended to appeal to dinner-party sensitivities.

It meant that angry denunciations of the Highland Clearances were transformed into such works as The Lady of Islay: a haunting love song.

Michael’s labour of love

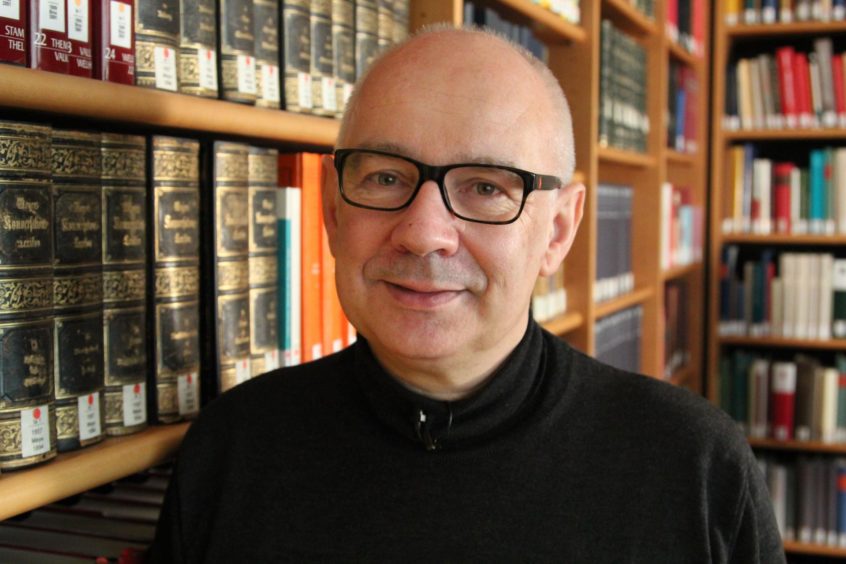

A German musicologist and Scottish scholar, Michael Klevenhaus, has spent more than five years researching the Gaelic origins of Beethoven’s compositions.

He became entranced by the language and culture of Gaelic Scotland, methodically learned the language and how to sing the ancient songs, and has founded the German Centre for Gaelic Language and Culture – which is a teaching institute in Bonn.

He subsequently examined the close connection between the Scottish songs of Beethoven and Haydn and the Gaelic musical tradition and earned his doctorate earlier this year at the University of Koblenz.

And, although he has been engaged in an abundance of research during his investigation, the end results have emphasised the strong links between one of the world’s greatest composers and songs with a derivation in the far north of Scotland.

The enchanting breakthrough moment

Mr Klevenhaus first became aware of the connection in 2015 while he was reading a scholarly work by piper Allan MacDonald, who had written a footnote stating that the song Enchantress Farewell, arranged by Beethoven with words by Scott, was based on Mhnathan a’ Ghlinne Seo (Women of the Glen).

It wasn’t quite a “Eureka” moment, but it inspired him to look closer into the bonds which were established between artists from often radically different backgrounds during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Mr MacDonald, from Glenuig, is somebody who argues passionately that music should have no barriers.

He said: “Nowadays, classical musical is viewed as being different from traditional music, but I don’t believe that is true.”

Neither does Mr Klevenhaus and the breakthrough prompted him to delve deeper into the connection between Beethoven and Gaelic songs and eventually sparked his conviction there could be plenty more tunes lurking in the works of the maestro.

From Bonn to Glasgow with Beethoven

That was the catalyst for him to embark on a journey of discovery to find the original Gaelic music and establish links with some of Scotland’s leading Gaelic luminaries.

The BBC Alba film follows Mr Klevenhaus’ odyssey as he travels from Beethoven’s birthplace in Bonn to Vienna and thence to a variety of locations in the Scottish Highlands, islands and lowlands to carry out research and meet several of the finest Gaelic singers and musicians, including Mairi MacInnes and Donald Shaw, the latter of whom is the co-founder of Capercaillie and artistic director of Celtic Connections.

With their help, he has unearthed the hidden Gaelic melodies that underpin the Beethoven works and discovered that the songs’ origins and lyrics were often deliberately hidden from the composer and the public by Mr Thomson, who originally commissioned the arrangements.

Jacobite rebellion was airbrushed from the works

Recognising that the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion still within living memory during Beethoven’s life (from 1770 to 1827), middleman Thomson took a conscious decision to strip the Gaelic songs of their titles, lyrics and the merest ‘taint’ of Jacobitism which had fallen into disrepute after the defeat of Bonnie Prince Charlie and his forces at the Battle of Culloden in 1746.

And this happened, despite the fact that he couldn’t even speak Gaelic.

Mr Klevenhaus said: “Gaelic songs are often highly political, but the meaning of these songs was hidden from Beethoven.

“Beethoven was a strongly political [figure] and, if he had been sent those words, what different songs we would have today!

“What would a radical republican like Beethoven have made of a political song by Sìleas Na Ceapaich, about people rising united against the king?

“It has been fascinating to discover the highly political nature of some of the original songs. It seems likely that these songs were deliberately sanitised to make them more suitable for an upper-class Lowland audience.”

The revelations have sparked anger among some members of the Gaelic music community – one described it as “disgraceful” – but Mr Shaw said it was time such findings became common knowledge.

He added: “This is where an uncomfortable truth comes to the surface and this [revision of lyrics] has been a common situation with ethnic music.

“However, we are living in a time where people are looking for more transparency in society and in politics. So why shouldn’t this happen in music as well?”

Ludwig’s other links to Scotland

Beethoven also took a keen interest in Ossian, the purported author of a cycle of epic poems which were published by the Scottish poet James Macpherson from 1760.

He was the first Scottish bard to gain an international reputation – Robert Burns followed in his footsteps as the 18th century progressed – and his work attracted a litany of international admirers, ranging from Napoleon Bonaparte to Thomas Jefferson, who regarded Ossian as “the greatest poet that has ever existed”.

Beethoven was an aficionado and devised plans to turn Macpherson’s works into a new opera. And, although that venture didn’t come to fruition, the German maestro never relinquished his interest in the songs from the Uists.

The programme concludes with a concert of the material, featuring a variety of musicians and singers from Scotland, Germany and Austria, at the most recent pre-pandemic Celtic Connections.

Mr Klevenhaus admitted to feeling nervous before the event, but the enthusiastic reception from an audience of all ages and backgrounds in Glasgow told its own story of how Beethoven’s music can transcend genres and generations.

The documentary Òrain Ghàidhlig Beethoven will be broadcast on BBC Alba on Wednesday, December 16 at 9pm, followed by a concert of Gaelic songs and Beethoven’s arrangements of them – Beethoven: A’ Chuirm Ghàidhlig – at 10.30pm.

Preview: an intriguing musical mystery for the ages

Michael Klevenhaus has the attitude that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains and his passion for his subject shines through in this new BBC Alba documentary.

As a fluent Gaelic speaker, who has brought a touch of the Hebrides to the heart of Germany, he has travelled thousands of miles to visit experts and spend time in the company of the musicians who keep alive the old traditions in the Western Isles and showcase these works to the world at Celtic Connections.

There is a genuine frisson and anger as Mr Klevenhaus carries out his investigations and gradually discovers how George Thomson did his best to sugar-coat some of the most haunting Gaelic compositions and delete any references to the political and military ferment which existed in 18th and early 19th century Europe.

But there is also a feeling of joyful discovery as Mr Klevenhaus – a naturally talented communicator and presenter – embarks on a series of compelling journeys to the Uists and to libraries and concert venues in Scotland and his homeland.

His conversations possess a real potency and poignancy, even as the locals on Lewis and Harris occasionally wonder why the cameras have turned up at various gatherings. And there are even moments where his persistence brings to mind the dishevelled detective Columbo, as he keeps chipping away at his nagging doubts and questions.

If you enjoy a good mystery with wonderful music from both the classical and traditional canons – and a heartwarming finale – this is an early Christmas cracker.