In my mid-twenties, I moved from Sudan to Scotland. I landed at Aberdeen airport with a four-year-old son, a two-week-old baby, and a husband working on the North Sea oil rigs.

Everything in my life so far had made me confident that I would find the move easy. My English was fluent, my upbringing in Khartoum had been westernised; I settled in full of optimism.

I liked Aberdeen, my husband was wonderful, my boys were thriving – I had no complaints. But, then, I was struck by homesickness.

It gripped me like a virus, affecting my body and movements. I sleep-walked through each day, aching for home. Its colours and sounds. Its own peculiar lifestyle.

My parents visited, and many of my friends were no longer in Khartoum, but none of that made a difference. It was the place I was missing, and my place in it.

I pushed the baby down Holburn Street, oblivious to my surroundings. Everything in Aberdeen felt dull, muted, like my life was on pause. Every single night, I dreamt of Khartoum and the house where I grew up – vivid dreams full of colours and warm laughter. When I woke up, I was surprised to find a cold, grey morning.

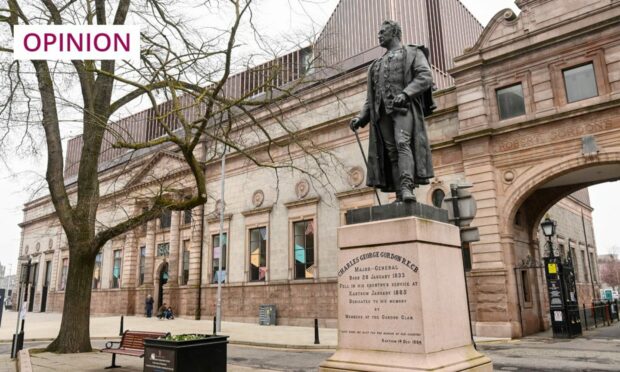

Then, right in the middle of the city, I spotted the name of my love. The word “Khartoum”, chiselled in stone. It was like an electric shock.

The word was on the inscription of a statue I had passed many times on Schoolhill. I had never cared to see whose statue it was. But, now, when I looked, I realised that I knew that man: Charles Gordon, governor general of Sudan, who was killed in Khartoum in 1885 by revolutionary forces.

They had put Khartoum under a tough siege for several months while Gordon held out, standing on the roof of his palace, looking out with his telescope over the Blue Nile, waiting for the British relief expedition. When it did arrive, it was too late.

An unexpected connection

At school and university, I had studied this period of history; Gordon’s story was familiar to me. Now, here he was in Aberdeen, huge in bronze, right in front of me – Gordon of Khartoum, my Khartoum.

Gordon was a lauded Victorian hero. His death, at the hands of a rogue assassin, and the hacking off of his head was a national trauma for Britain. Queen Victoria wept and statues, such as this one, were erected in his honour.

In the 1960s, Hollywood glamourized him with the epic war film Khartoum, in which his character was played by Charlton Heston. Laurence Olivier, in blackface, played his Sudanese adversary.

But the real Gordon was his own worst enemy. He believed himself to be exceptional. Delusional and stressed by the siege, he forced the British Government to send in an army to rescue him. His stance resulted in the death of many Sudanese people. If he had surrendered Khartoum instead of holding out at all costs, its citizens would have been spared much bloodshed.

Gordon was an imperialist and a racist, opining in his journals that all black women were sluts. Yet, coming across his statue at a time when I felt alienated and miserable, my only reaction was to be thrilled by the connection.

Here was a public assertion of my identity: proof of a shared history. Gordon had been there, and I was now here.

The university I had graduated from, the University of Khartoum, started out as Gordon Memorial College. The palace where he died was walking distance from my school. The Blue Nile he gazed at every day had watered my ancestors for generations.

There were around five statues of Gordon dotted around Britain: what were the chances that one of them would be in front of me?

I built a fulfilling life in Scotland

Steps away from Gordon’s statue was the public library. I joined and began to read. Having trained as a statistician, I now started to read books about immigration, women’s lives, and postcolonial literature.

I learned that my circumstances were not unique, and that the cure for my malaise was to do things I would not have done in Khartoum. So, I read Scots, gave talks about Islam in schools, wrote novels.

Gradually, my homesickness started to fade. It became manageable, flaring up from time to time in moderation

We never did go back and live in Khartoum. But, by writing about Sudan, I built a fulfilling life in Scotland. Gradually, my homesickness started to fade. It became manageable, flaring up from time to time in moderation, without crippling my life.

Now, when asked, I say I am from Aberdeen, not Khartoum. I can still, though, visualise what Gordon must have seen with his telescope, the sun hitting the downstream flow of the Blue Nile, birds flying over the fields on the other side, and the neem trees lining the waterfront.

Leila Aboulela is a fiction writer, essayist, and playwright of Sudanese origin, based in Aberdeen. Her latest book, River Spirit, is out now

Conversation