In The Long Shadow, the television dramatisation of the notorious north of England murders by Peter Sutcliffe in the 1970s, what emerges clearly is the institutional misogyny of the police, and the way an organisation’s structures affect its performance.

It would be easy to watch with a sense of “weren’t they weird in those days?” But the most disturbing thing about the attitudes that left Sutcliffe uncaptured for five years, despite being interviewed by police nine times, is that they are not consigned to history. Fifty years later, they still exist.

Important as the glass ceiling may be for individuals trying to advance their careers, it is the structural effects of the ceiling that affect women most deeply. Remove women from decision making (or men, for that matter) and outcomes get skewed.

The announcement by Lord Advocate, Dorothy Bain, of changes to Scotland’s law of corroboration in the prosecution of rape cases illustrates why appointing women to key structural roles is so important. Women’s experiences are finally being recognised in law. Why? Because the Lord Advocate is a woman. Rocket science, huh?

Victims’ distress following rape will now count as corroboration, bringing Scotland into line with other countries; progress described as “seismic” by campaigners. More women will access justice. But we’ll come to that. The history of this is important: seeing the concertina chain that stretches between “then” and “now”, linking the decades together.

Notion that women are to blame for their own attacks has been perpetuated for too long

Sutcliffe was prosaically dubbed “The Yorkshire Ripper”, to the fury of his victims’ families, in a titillating nod to the Victorian London prostitute murders by Jack the Ripper. Like this was some unsolved crime yarn, rather than the tragic destruction of women’s lives. The real link between Jack and the Yorkshire Ripper wasn’t the crime, but society’s depersonalisation of “a certain type of woman”.

Many of Sutcliffe’s victims were prostitutes – but not all. It was, in any case, irrelevant. They were women with lives and families, with troubles and traumas, and their existence had as much meaning as anyone else’s. Their lives were just as valued by those who loved them.

The police’s insistence on “boxing” them was an indication of a prejudice that demands a hierarchy of victimhood. One woman was refused criminal injuries compensation because she denied she was a prostitute, and because she had “brought the attack on herself”.

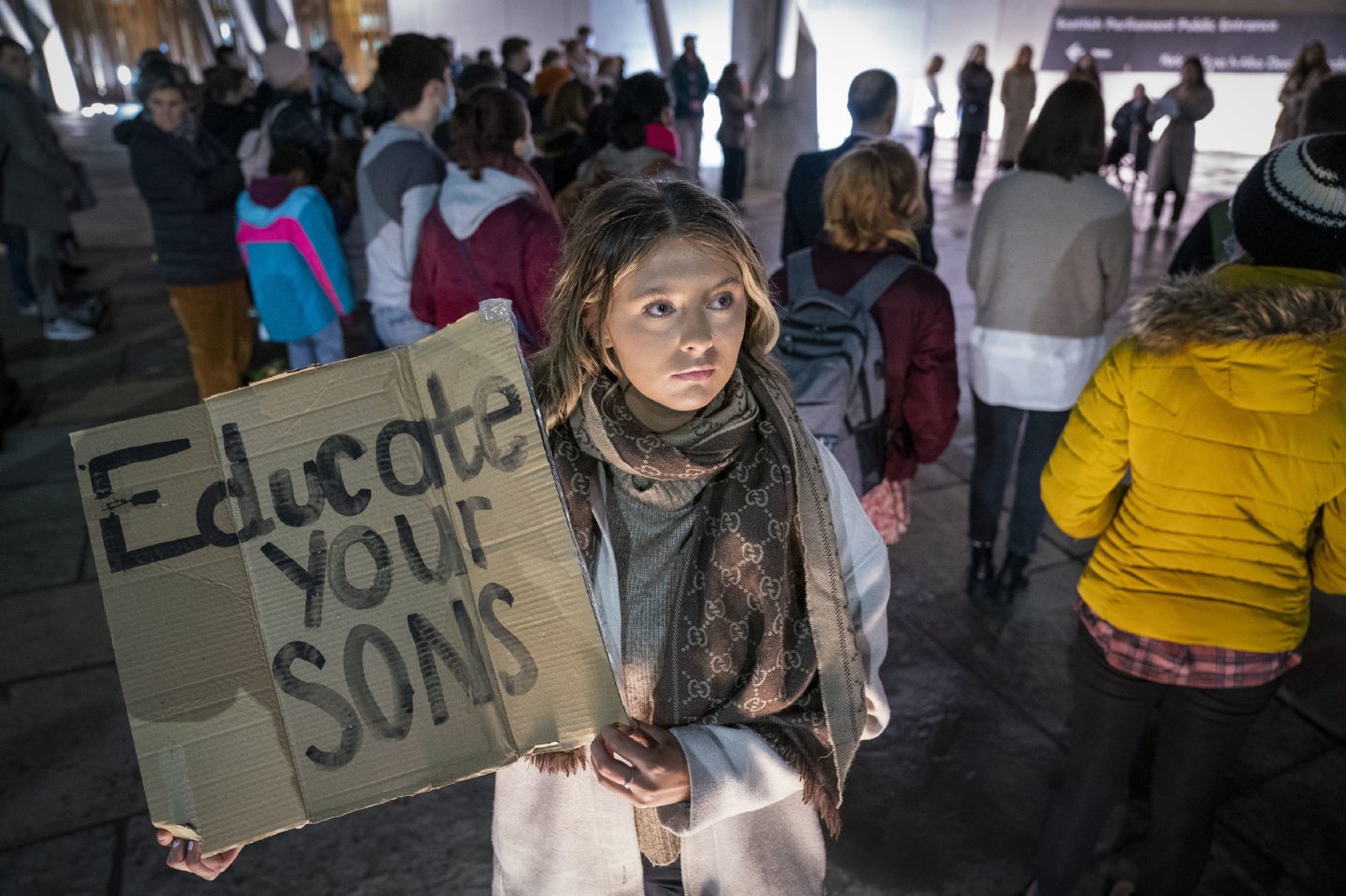

The notion that women are to blame for their own attacks has been a persistent theme for generations. Asked for his advice to women, the police chief in Sutcliffe’s time said: “Stay home. Stay safe.” By the time Sutcliffe had killed 13 times, women were publicly demonstrating, carrying placards with his words, “stay home” on them – except the word “men” had been scribbled at the top. Men stay home. Perpetrators stay home.

The same message was heard 50 years later, when crowds demonstrated after the murder of Sarah Everard. Women refused to be blamed and shamed or curfewed.

Twenty years after Sutcliffe, a series of prostitute murders in Glasgow in the 1990s saw the public being reassured that “ordinary” women were safe.

The women were lost but the man was caught. Hey-ho

We were meant to feel better that this wasn’t a single serial killer but a series of men whose psychopathy apparently halted when they left prostitutes and met “normal” women. Deserving women. Ten years after that, we had more victim shaming in the Ipswich prostitute murders of 2006.

Realising history is still current is sobering

In The Long Shadow, female police officers are sidelined while male officers display all the perspicacity of PC Plod. The male officers’ attitudes to prostitutes display a disturbing mix of salacious, sexual curiosity and contemptuous judgment. Perhaps that was what enabled the investigation’s most damaging element of all to creep in: it was not driven by empathy for victims and families, but by the challenge of the chase.

Investigators feared more victims because they feared public humiliation. One of the most shocking moments is when Sutcliffe is finally caught. The top brass are shown laughing with relief during a press conference, while families watch, horrified. The women were lost but the man was caught. Hey-ho.

Watching history and realising it’s still current is sobering. Would Sutcliffe have been caught sooner had women been included in decision making? Maybe.

If The Long Shadow emphasises anything, it is the importance of women gaining access not just to senior roles, but to the structural mechanisms of power.

Dorothy Bain will not change things because she is a good KC. She will change them because she is Lord Advocate and can challenge legal structures. “Since my appointment,” she said, “I have sought to do all within my power to deliver justice for women and girls, who are disproportionately impacted by sexual offences.”

The Sutcliffe victim refused compensation because she denied being a prostitute eventually received £17,000.The senior cop sold his story to The Daily Mail for £40,000. Men’s words outweighed women’s words back then, just as they still do now. Time for women to take equal charge of the dictionary.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter

Conversation