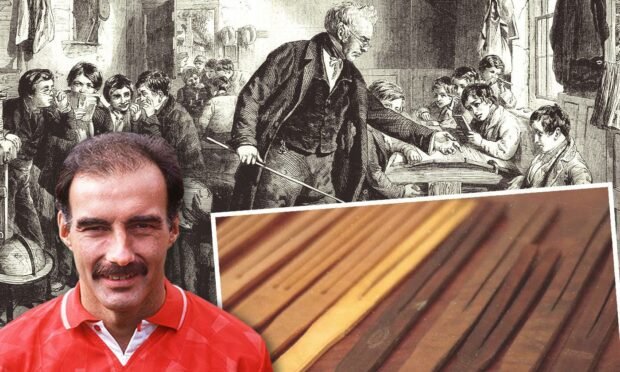

Millennials will probably regard it as the equivalent of sending children up chimneys or locking up Suffragettes.

But there was a time, and not so long ago, when it was perfectly acceptable for a teacher to punish a “naughty” child by giving them the belt or, more accurately, whacking them with a large leather strap.

Sometimes, if a particular tutor was in a bad mood or was losing control of their class, the victim might not even have done anything wrong.

But that still didn’t prevent them from getting beaten with two or three strikes – or what was euphemistically described as “six of the best”.

Union head said ‘carry on caning’

Eventually, as the 1980s arrived, two Scottish mothers, Grace Campbell and Jane Cosans, joined forces to try to have corporal punishment banned.

But although they went to the European Court of Human Rights and, finally, 40 years ago this month, nominally won their battle to have the practice scrapped, nothing happened quickly thereafter, as the belting continued.

Indeed, David Hart, the then-general secretary of the National Association of Head Teachers, said the judgement – which did not prohibit caning – would cause “confusion in schools” which “will have to distinguish between children who are allowed to be beaten and those who are not”.

Then he added: “My advice to members is – carry on caning”, which thankfully wasn’t turned into a movie with Kenneth Williams and Barbara Windsor.

But the controversy rumbled on and Aberdeen was one of the last cities in Britain to ditch the tawse – many of which were made in Lochgelly in Fife.

Supporters of the belt argued it was a short, sharp means of imposing discipline that caused temporary pain to the recipient but left them with a motivation not to repeat their misdemeanour.

Critics retorted that Britain was the only country in Europe that still used the strap as a deterrent and pointed out there was little evidence that pupils in the UK were any better behaved than their counterparts in France, Germany, Scandinavia and elsewhere.

However, despite repeated calls for it to be outlawed, Aberdeen councillors couldn’t agree on a timeframe or an alternative, such as detention or lines, which wouldn’t require teachers to work extra hours.

One stormy meeting in 1984 summed up the confusion.

As the Press & Journal reported: “The belt will be banned in all Grampian’s schools by August next year (it wasn’t) – but only if the Westminster Government provides cash for alternative forms of discipline (it didn’t).

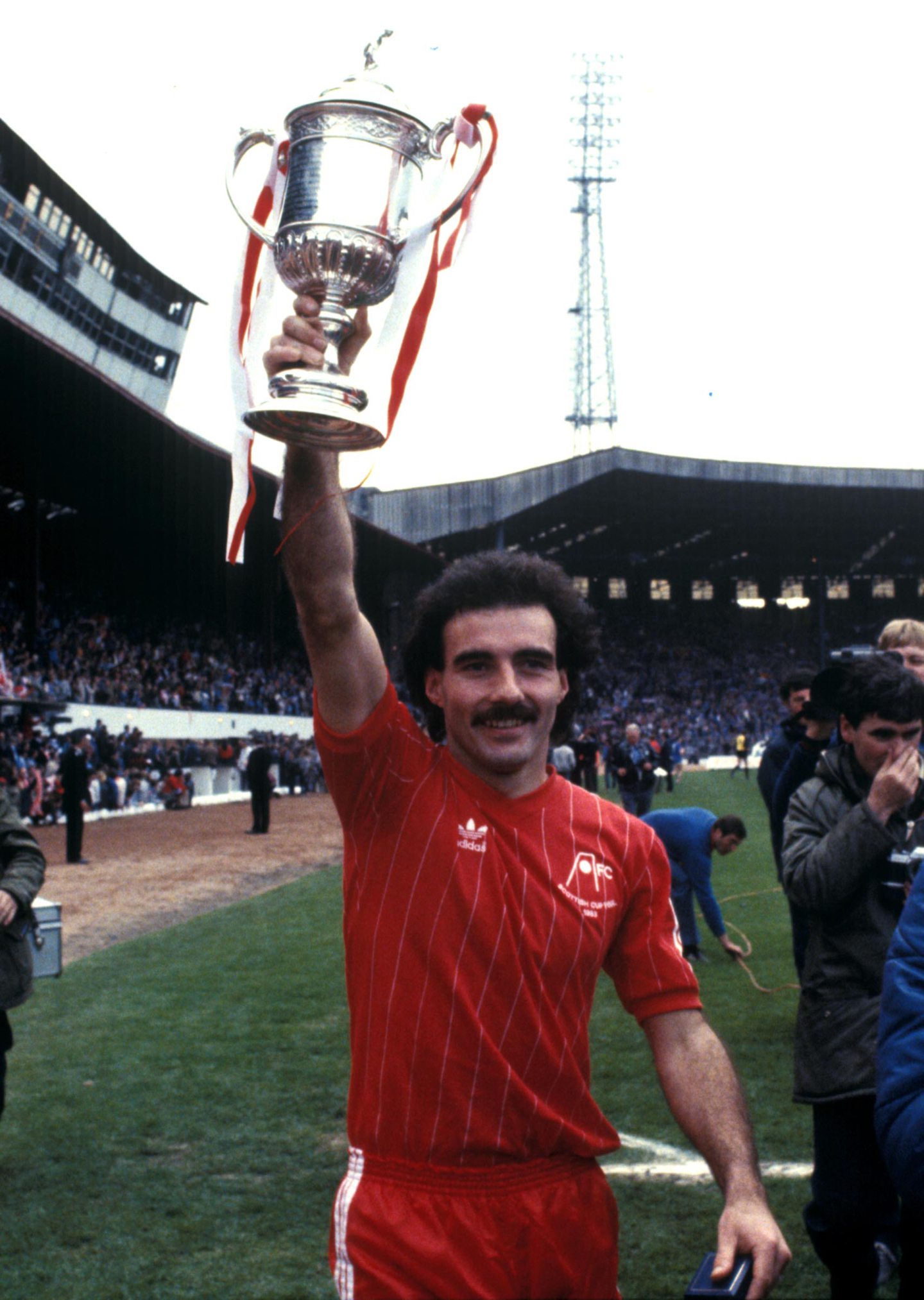

I’m glad that it’s gone now, for the sake of my own children.”

Aberdeen FC great Willie Miller

“This was the outcome of a lengthy, heated and confused debate at the region’s education committee. The ruling Tory group was split between whether the belt should be kept or it should be scrapped.

“One Labour councillor (Eric Hendrie) came under considerable fire for his comment that the use of the strap was a form of cowardly assault.

“And Liberal councillors wanted nothing to be done until the Westminster Government provided money for additional resources in schools.”

The status quo prevailed and the beltings continued.

It wasn’t until 1987 that north-east youngsters were eventually spared a session with “the scud”, as many pupils in the region had come to call it.

Very few escaped getting the belt

Mr Hendrie had fought for a quarter of a century to bring about the end of corporal punishment, which he described as teachers assaulting pupils.

But, for a long time, his was a pretty solitary voice.

The Evening Express in 1982 reported on how most people still favoured “sensible use of the belt” as the best way to deal with students stepping out of line.

Gradually, however, the public mood started to shift in his favour and he was relieved as well as delighted when the belt was locked away forever.

‘Schools were a place of fear’

He said: “The ban was needed, but it’s a shame that it took so long for it to happen. You can imagine what a great day it was when we finally won.

“My generation’s memory of it is that schools were just places of fear. My childhood memories were not at all happy because of it and I wasn’t alone.

“I recall one time when I was running my fingers through my hair or something and the teacher accused me of waving to someone outside, dragged me out, and belted me in front of the class.

“We were three floors up and there wasn’t a soul outside, so you can imagine I felt a great sense of injustice. I was around 10 at the time, so that was nearly 60 years ago and I’m still angry about it.”

It was sore for a few minutes but, you know what, I never did it again.”

David Mitchell

Most other parts of Scotland took action to resolve the issue quicker than occurred in Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire.

Grampian Region, which resisted a voluntary ban on the tawse, was one of the last local authorities in Scotland to ban corporal punishment in schools when legislation was passed in August 1987.

And a lengthy survey in the Evening Express afterwards revealed just how many people had different recollections of their brush with the belt.

Gothenburg Great Willie Miller was among those who offered his views and it was clear he was glad the ban had been introduced.

He said: “If I did misbehave, it was looked on fairly sympathetically, because I was a member of the football team. But I was belted once for playing football when I should have been in class.

“I’m glad that it’s gone now, for the sake of my own children.”

Former city councillor Bob Middleton, who attended Aberdeen Grammar School, shared that view and explained he had been regularly punished.

He added: “I was belted for different things like forgetting to do my homework or for speaking in class. And I tried to have it banned earlier.

“I’m sure that it wasn’t the answer to discipline in schools.”

‘It never did me any harm’

Nonetheless, despite the belated ban, some people still reckoned that corporal punishment was the “least bad” of the available options.

David Mitchell, from Ellon, told the Press & Journal in 1987: “I’ve read all about how horrible the belt supposedly was but if you did something wrong at school then I think you deserved to be punished.

“I forgot to do my homework once and I got belted the next day. It was sore for a few minutes but, you know what, I never did it again.

“Looking back now, that was fair enough. It never did me any harm.”

Eventually, but only after a lengthy campaign, the belt was no more.

But the Press & Journal and The Courier both reported in the years ahead how many teachers were concerned about increasing problems with lack of discipline.

Exclusions were regarded as a last resort by the authorities while other punishments such as detention or lines – as witnessed at the start of many episodes of The Simpsons – required teachers to stay behind in class.

Thankfully, there seems to be greater cooperation between parents and teachers in many places. But problems still arise in schools.

In short, whether or not you agree that the belt was barbaric or a necessary evil, banning it wasn’t a panacea.

Pain of getting the belt never left me

As somebody who went to school in Scotland in the late 1960s and 1970s, the belt was an occupational hazard and few people escaped its stinging lash.

Occasionally, when pupils went so far as to start fights in the classroom or use swear words, the teacher would bark: “Right, the next person to misbehave is getting belted”.

It was often that random. And there were always one or two who seemed to enjoy making a pupil cry when it suited them.

In one case, I definitely earned my punishment. That was the occasion where I threw a snowball at another pupil and was horrified when it missed its target and crashed into an imposing teacher.

Worse still, the snow I had picked up was accompanied by a bit of dog dirt. A painful mistake!

Most teachers used it as last resort

But there were a number of rogue teachers who derived pleasure from whacking those they perceived as impudent or cocky – or sensitive.

I recall one of the PE masters picking on a chubby kid who couldn’t climb up a school rope – neither could the rest of us in the class – and the pupil told him quietly: “I’m not doing it again, sir, my hands are sore”.

This enraged the teacher and he ordered the boy to put his hands together and struck him once, twice, thrice – until there was blood on the victim’s hand and he was sobbing in pain.

At that point, nobody could possibly have defended the belt, nor have excused that master’s actions.

It was excessive violence against a minor by somebody in an educational establishment.

And, in retrospect, that is why it had to be consigned to history.