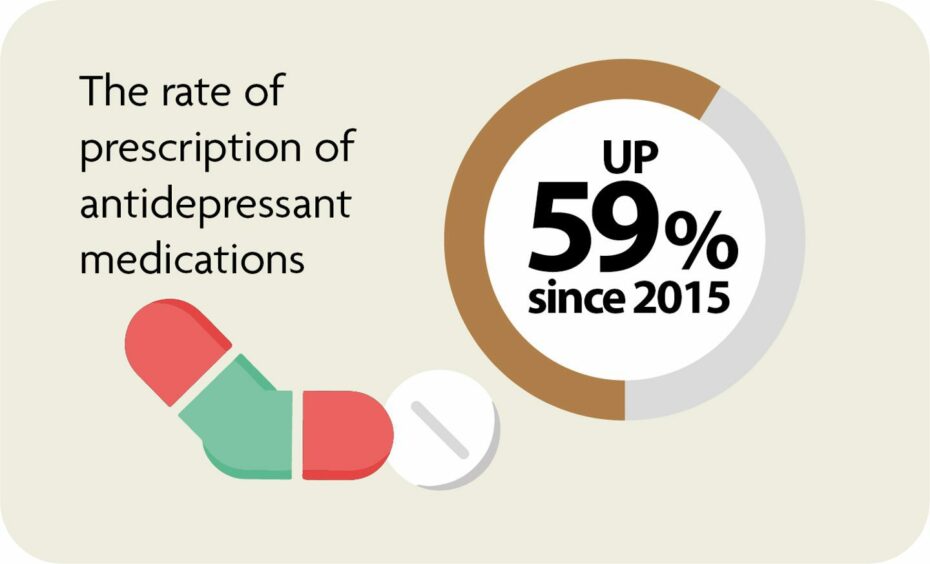

Mental health prescriptions for children in Grampian have risen by nearly 60% since 2015, according to researchers.

A study carried out by Aberdeen University looked at NHS Grampian medical records on children between 2015 and 2021.

Alongside an increase in prescriptions, researchers also discovered differences in mental healthcare depending on gender and wealth of families.

In total, there were 176,657 mental health prescriptions and 21,875 specialist outpatient referrals for 18,732 children during that period.

The number of prescriptions for antidepressants rose by 59%.

Meanwhile, prescriptions for ADHD medication went up by 45% and prescriptions for psychoses and related disorders increased by 35%.

The project is being led by Dr Jessica Butler who said the team discovered a “big gap” in the system.

She added: “GPs are giving many more mental health prescriptions, but there is a limit to who can be seen by hospital specialists.

“This research shows that how we close that gap and improve mental health, will be different for different children. Boys and girls may need different care, as may children who are living in poverty.

“Ideally, we use this research to help prevent poor mental health before children need specialist services.”

Differences between boys and girls

The research was completed by the Networked Data Lab team at the university in collaboration with The Health Foundation.

Their findings have now been published in BMC Psychiatry.

Researchers discovered consistent differences in the mental healthcare for boys and girls when it came to prescriptions and referrals.

Boys received 73% of all mental health prescriptions, mostly to treat ADHD, and more prescriptions than girls in primary school.

For 10-year-olds, there were 1,200 mental health prescriptions for boys and 300 for girls.

However, there were more prescriptions issued for girls in secondary school, with the majority being for antidepressants.

A total of 1,800 17-year-old girls had a prescription compared to 1,300 boys the same age.

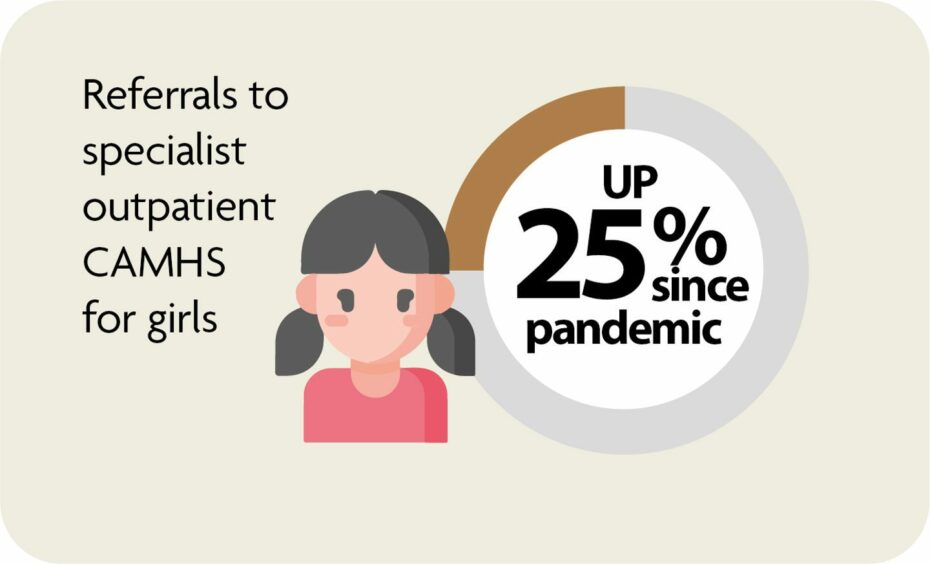

The pandemic has also marked a shift in the number of children being referred to mental health specialists.

There was no difference between boys and girls prior to 2020, but since then referrals for girls have increased 25% while they have gone down 6% for boys.

In 2021, girls made up two-thirds of those accepted for care at NHS Grampian’s Children and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS)

Impact of poverty

The study found that children who live in more deprived areas across Grampian needed more mental health care.

They received twice as many prescriptions for mental health medication as children living in neighbourhoods considered wealthy.

Researchers also discovered that children in deprived areas had twice the rate of referrals to specialist mental health services.

Those children who were referred were also younger in age.

William Ball, a research fellow in the Network Data Lab, said: “One in six children in the UK are estimated to have a mental health condition, and many do not receive support or treatment. The pandemic appears to have exacerbated this issue.

“The large increase in mental health prescribing and changes in referrals to specialist outpatient care aligns with emerging evidence of increasing poor mental health, particularly since the start of the pandemic.

“Our analysis shows that the prevalence of poor mental health is something which affects groups of people differently based on age, sex and socioeconomic circumstances.

“Teenage girls and children living in less affluent areas are particularly in need of support.

“Persistent and avoidable inequities in mental health prescribing and referrals require urgent action.”

‘Issues not unique to Grampian’

A spokeswoman for NHS Grampian’s CAMHS explained some of the different challenges facing the team, pointing that those living in poverty are “more likely” to have complex challenges which result in prescriptions being required.

She stressed prescriptions are given after other interventions have been tried, with all decisions about medication made by a team made up of psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses and allied health professionals.

The spokeswoman said: “We are seeing an increase in the acuity and complexity of the challenges children and young people are presenting with, and we’re seeing a steady increase in the number of referrals every year – which also increases the number of prescriptions issued, not only by CAMHS but a range of health teams. This is not an issue which is unique to Grampian, nor are the gender and age differences in terms of who is prescribed medication.

“Children and young people living in poverty are more likely to present to us with more complex challenges than their more affluent peers. This would explain why they are more regularly prescribed medication and this also demonstrates positive progression in that historically ensuring children and young people living in poverty are as likely to be referred and get the help they need has been a challenge.

“The way the data has been presented in terms of how many referrals are rejected or redirected is misleading. Until 2021 we did not have appropriate systems in place to record all referral data fully but this has improved with the introduction of the CAMHS National Referral Criteria and Guidance. This led to all queries being recorded as referrals, however, and more recently we introduced a new patient management system. In time, this should be able to provide a much more clear and accurate picture of how referrals are handled.”