It’s 75 years since a grateful British nation paused to commemorate the memory of the myriad men and women who sacrificed their lives during the Second World War.

Although the conflict had officially ended in August 1945, there were still service personnel arriving back in the north east of Scotland until October and even November, whether returning from prison camps in the Far East or recovering from their injuries.

Many of these soldiers never spoke about their experiences after coming home.

At that stage, even though they were burdened by the effects of post traumatic stress disorder, the condition had not been diagnosed, let alone understood, and so they suffered in silence.

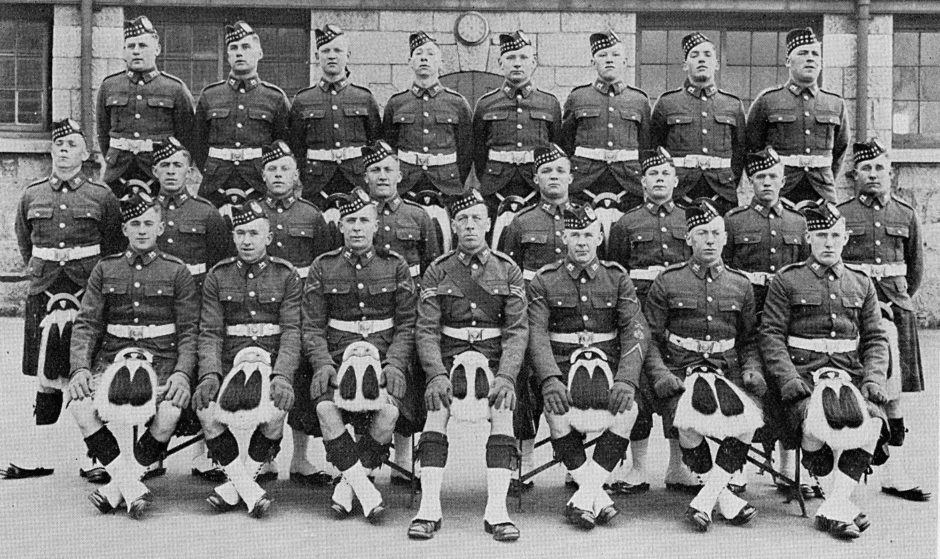

Old photograph

Stewart Mitchell, the volunteer historian at the Gordon Highlanders Museum in Aberdeen, has investigated the fate of so many who joined the regiment in different circumstances and unearthed how whole communities were affected by the hostilities.

He has also highlighted a photograph from 1934 which reveals the faces of a group of young men who enlisted from the Granite City, Aberdeenshire, Banffshire and Moray, often because they were seeking an alternative to the worst privations of chronic poverty, economic deprivation and lack of job opportunities.

Even now, their stories emphasise why Remembrance Day matters and why it will still be commemorated even though there are no mass gatherings because of Covid-19.

Mr Mitchell explained the manner in which numerous lives were changed irrevocably in the period between the mid-1930s and a decade later.

He said: “This was the time of the great depression, when unemployment was high. In these hard times, many young men turned to the army to provide a secure future, which catered for all their needs, provided training and offered the possibility of foreign adventure.

“This was only sixteen years after the end of the Great War, ‘the war to end all wars’ so it was widely believed that the threat of another conflict was unthinkable.

“The 1934 photograph pictures these men at their ‘passing out’ parade, when they had just completed their basic training at the old Castlehill Barracks in Aberdeen.

“Almost immediately after this was taken, they were posted to their battalions, where they would spend the rest of their military careers.

“We can trace the movements of most of these men and we know that five went to the 1st Battalion while 11 joined the 2nd Battalion.”

Cruel hand

He added: “Fate dealt this group a cruel hand and almost none of them came through the Second World War unscathed.

“When it started, on September 3 1939, the 1st Battalion was mobilised immediately and sent to France.

“The rapid advance of the Nazis overwhelmed the British Expeditionary Force and the ‘miracle of Dunkirk saved many troops, but not the 1st Battalion when almost 2,000 Gordon Highlanders were captured at St Valery-en-Caux in June 1940.

“Among these were five of the group who spent the war in the Stalags in Germany and Poland, where they were forced to work for the German war effort, including in quarries, coal and salt mines where health and safety considerations were non-existent.

“As the war in Europe was drawing to a close in January 1945, the German force-marched their prisoners away from the advancing Allied armies during blizzards and sub-zero temperatures, and, for many months, they spent nights with little food or little shelter.

“Although our entire band survived, it was a very close-run thing with the constant challenges presented by the conditions and the dangers of being killed by the enemy or by what is now described as friendly fire.”

Pearl Harbor

The 11 men with the 2nd Battalion were stationed in Singapore and escaped the ravages of the war for the first two years of the hostilities, but that changed dramatically when the Japanese simultaneously attacked Pearl Harbor and Singapore in December 1941.

Their rapid advance through Malaya stunned the British and Australian Allies and around 60,000 men were forced to surrender in February 1942.

“This figure included almost 1,000 of the 2nd Battalion Gordon Highlanders and it was the start of a dreadful time for these poor fellows, trapped in a terrible situation.

As Mr Mitchell said: “Prior to the surrender, 14 key Gordon Highlanders, including Victor Aitken, were evacuated from Singapore.

“Tragically, they were all lost at sea when their ship was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine in the Indian Ocean. Then James McIntosh died shortly afterwards in Singapore, of dysentery.

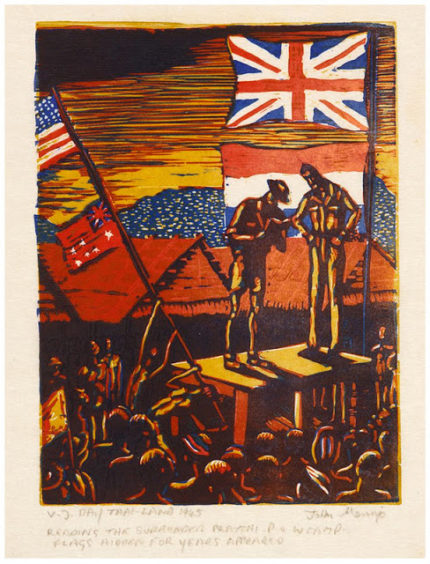

“Nine of the eleven 2nd Gordons were sent to Thailand to work on the infamous ‘Death Railway’ where Alex Wilson and Donald Ness both perished as a result of the brutal treatment which was meted out by the Japanese guards, while also suffering from deadly tropical diseases and starvation.

“After the railway was completed, in October 1943, the Japanese were not finished with their prisoners. David McMaster, Alex Hepburn and Anthony Cobban were sent to Japan in ‘hell ships’, so called because the POWs were kept below decks in insanitary conditions, with little ventilation and given little food or water during the long voyage.

“Anthony Cobban and Alex Hepburn were shipwrecked when American planes bombed and sunk their ship, which had no marking to warn the Allies there were Allied POWs on board.

“Fortunately, both Anthony and Alex were rescued and made it to Japan, but of the 105 Gordons who made this hellish journey, only 33 survived.

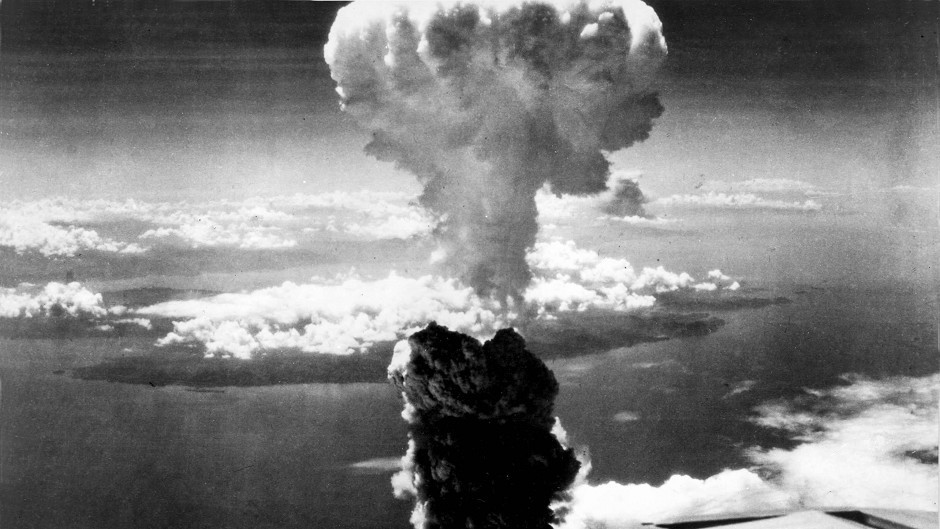

“As the war came to a close in August 1945, Alex Hepburn witnessed the atomic bomb explode over Nagasaki which was the final straw that forced the Japanese surrender.

“David McMaster was forced to work at Funatsu (Nagoya) POW camp, near the port of Osaka in Japan, where the main activity was mining and the refining of lead and zinc.

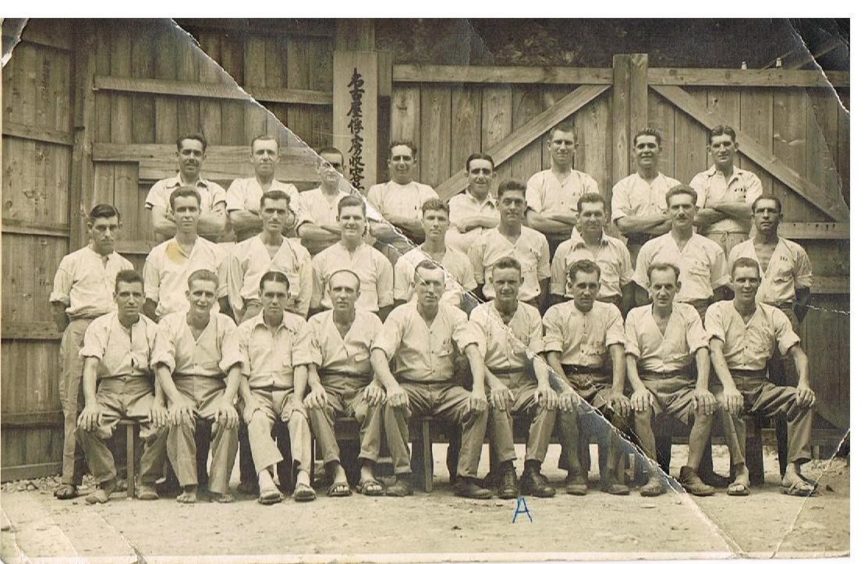

“There were at least 19 other 2nd Battalion Gordon Highlanders at this camp who were liberated by American forces on September 6 1945.

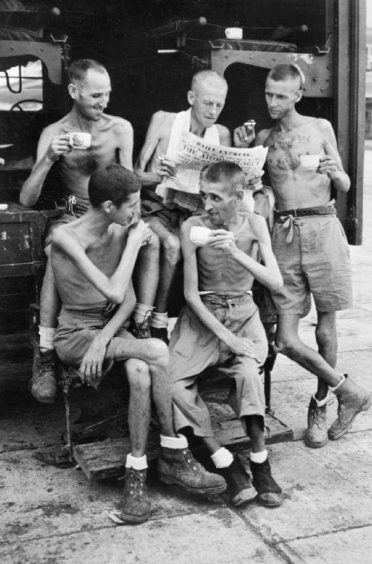

“And we have a poignant photo of some of these men, shortly after their liberation at this camp.

“David McMaster is in the centre of the front row and next to him, marked by the letter ‘A’ is his close friend, Gordon Highlander Alex Smart.

“Although there is likely to be a number of other 2nd Battalion Gordon Highlanders in this picture, the only one we currently know is John Wood, who is the man second from the right hand end of the middle row.

“Before repatriation to Britain, the men who were liberated in Japan were taken to Australia or the west coasts of Canada or the United States, where there was a plentiful supply of food, to allow their physical strength to recover.

“This delayed their return to Scotland. David McMaster and Alex Smart travelled by rail right across North America and came home from New York on the converted liner the Queen Mary, arriving in Southampton the end of October 1945.

“John Wood returned home from Australia a little later in early November. The men from Thailand and Singapore arrived back to Liverpool in the latter part of October.”

Relief

Once they were with their loved ones again, there was relief rather than exultation. As the late Eric Johnston said after returning to Aberdeen: “We went away as boys who thought it would be a big adventure without wondering why our mothers and fathers were so worried.

“We didn’t realise what on earth we were getting ourselves into.”

Thousands were denied a reprieve and their ashes are scattered under the midnight sun or their bodies consecrated in graves in a variety of little graveyards across Europe.

It is for them and their predecessors who were slaughtered in appalling numbers in the trenches, at sea and in the air during the First World War that the nation stops for a few minutes every November.

Mr Mitchell said: “Remembrance Day in November 1945 must have been a very emotional day for all those who had returned, but many of them were troubled by their experiences and had nightmares and flashbacks on many more days and nights in the months and years afterwards.

“We should always remember the huge debt that we owe to all of them, not just the fallen but also the ones who returned.

“They were given little official support and depended wholly on the love and care of their families to mend their broken bodies and minds.”

No matter the restrictions which have been imposed by the pandemic, they shall not be forgotten.

Not only humans came home

Her grave is one of the first things you notice when you visit the Gordon Highlanders Museum in Aberdeen.

Peggy, a heroic dog, who comforted captured Scottish soldiers during the Second World War, was posthumously awarded a PDSA commendation at the museum earlier this year.

The bull terrier became the 2nd Battalion’s mascot after soldiers discovered Germany as an abandoned puppy in Malaya – which is now part of Malaysia – during the hostilities.

And this loyal canine was actually taken as a prisoner of war at the end of the ill-fated Battle of Singapore in February 1942.

Rations

The Japanese refused to feed Peggy, so the captives often shared their own rations to ensure she did not go hungry.

Prisoners were given no meat or vegetables, so she used her instincts to hunt for rats, which the soldiers would cook and add to their meagre rations of rice.

Peggy was eventually freed, along with the battalion after VJ Day on August 15 1945. Such was the bond between her and the Gordon Highlanders that the men refused to travel back to Scotland unless she was allowed to join them.

She subsequently made Aberdeen her home and lived at the battalion’s barracks until her death in 1947.

PDSA vet Fiona Gregge said: “Her remarkable story has touched all of us. It is clear that the soldiers drew a great deal of strength from Peggy’s unwavering loyalty and friendship.

“The fact that the Gordon Highlanders refused to board their ship home unless Peggy could sail with them speaks volumes about the bond that was formed.”