“Choose life. Choose mortgage payments; choose washing machines; choose cars.”

I know what you’re thinking. In this economy, life sounds expensive.

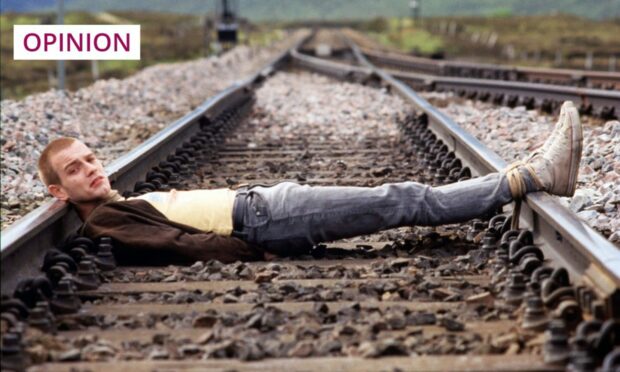

Thirty years ago this week, Trainspotting was published. Raw and shocking, both in terms of subject matter and style, the novel’s release was hugely significant. Its “choose life” quote was extended a few years later in Danny Boyle’s film adaptation, monologued and immortalised by Ewan McGregor.

Reflecting on the book three decades after the fact, its author Irvine Welsh said the tale of young people living in Leith in the grip of heroin addiction was meant to be something of a cautionary one. A part of him really did want readers growing up in deprived areas to choose a different path. Sadly, “you can’t really see it that way any more.”

“People can’t get jobs. People will never buy a house. They can’t buy nice things. Everything is f**ked even if you’re not on drugs,” Welsh told The Guardian just days ago.

Drug use was doing enough damage across Scotland in the mid-1980s for Welsh – who became addicted to heroin himself during his 20s – to start writing about it, recording his reality, but also sounding the alarm to alert more affluent people with the power to change things. Though dark and wry humour is applied liberally in his work, the pain and hopelessness of becoming stuck in a cycle of poverty and addiction is visceral.

Nonetheless, as we headed into the 1990s – when Trainspotting hit shelves and flew off them again – the situation grew worse. The number of people dying in Scotland as a result of taking drugs steadily increased, until our country’s drug-related death rate became and remained the highest in Europe, by a terrifying margin.

The Scottish and UK Governments’ lack of action on this issue has been shameful. We Brits like to make fun of the very American “thoughts and prayers” platitude, rolled out when yet another horrifying mass shooting happens stateside.

After Dunblane, we cracked down swiftly on gun ownership. Since then, there have been 20 recorded mass shootings across the UK. In the US, at least 300 have already happened in 2023 alone.

We can be proud that our leaders took action without hesitation, undoubtedly saving many lives. But why didn’t they do the same when it came to drugs?

By that, I don’t mean extending the long arm of the law because, of course, it did do that. Tens of thousands of drug-related offences are recorded by Police Scotland each year. At its peak in 2005-06, that number was 44,247 – some dealers, some users.

Clearly, Scotland’s war on drugs didn’t stop people from using and dying.

None of this is radical, new or likely to happen soon

Today (July 7), the Scottish Government called for Westminster to decriminalise the possession of all drugs for personal supply (or transfer the powers to do so to Holyrood), and championed the introduction of supervised drug consumption facilities.

Finally, the right policies are on the table. But none of this is radical or new – Portugal, for example, implemented these exact strategies decades ago, with great success. And, frustratingly, none of this could ever happen unless the UK Government gives the go-ahead. Predictably, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has already vetoed the idea, saying: “There are no plans to alter our tough stance on drugs”.

What stance is that? We’ll lock you up or leave you to die if you develop a dependency on a highly addictive substance? That is tough, right enough.

Between January and March 2023, there were 298 suspected drug deaths in Scotland. If you haven’t been personally affected by our country’s drugs death crisis, I guarantee someone you know has, even if you don’t realise. Family members, friends, colleagues are all suffering – often silently – as a result of avoidable, world-stopping loss.

Campaigners have been shouting for a better, more humane and more effective approach to lowering Scotland’s drug-related death and addiction rates for far too long. Prison time is plainly not the solution here.

We don’t arrest alcoholics for possession because, of course, alcohol is a legal drug – but, importantly, it is still a drug, no matter how stubbornly we pretend it isn’t. We don’t help alcoholics the way we should, either; we ought to be treating their illness with care rather than judging them for it.

‘Society cannae be changed’

Shame, stigma and hypocrisy are at the root of so many of our darkest problems. Despite what we claim, our society still sees addiction as a choice – a symptom of weakness or laziness – rather than what it is: a deadly disease. We feel the same about poverty – why can’t they just get a job?

The current economic meltdown will soon mean more families than ever slide below the poverty line, with little hope of escape without government empathy and intervention.

It isn’t a stretch to suggest we may well see our drugs death rate soar even higher as a direct result of today’s cost-of-living crisis

Data shows that deprivation and drug use have gone hand in hand since the 1980s, due to social, economic and political inequality; it isn’t a stretch to suggest we may well see our drugs death rate soar even higher as a direct result of today’s cost-of-living crisis.

Much has changed since Trainspotting was published but, on drugs, Scotland has stood still – perhaps even gone backwards, relatively speaking.

“The problem is that Tom refuses tae accept ma view that society cannae be changed tae make it significantly better,” the book’s narrator Mark Renton explains to the reader. Thirty years later, what have we really done to prove him wrong?

Alex Watson is Head of Comment for The Press & Journal and would rather not choose mortgage payments