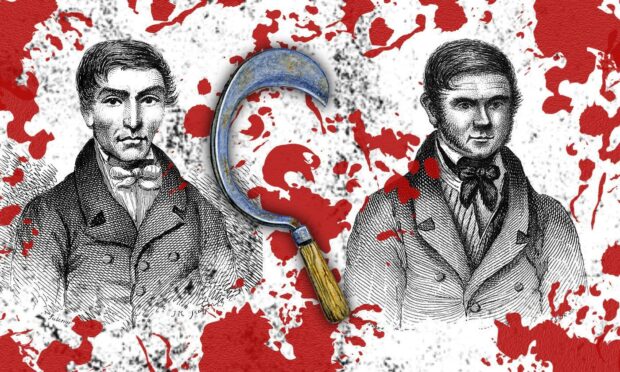

Could some innocent Highland labourers have been victims of the dreaded murderers Burke and Hare in 1828?

There were those who clearly thought so at the time, as contemporary letters to an Inverness newspaper reveal.

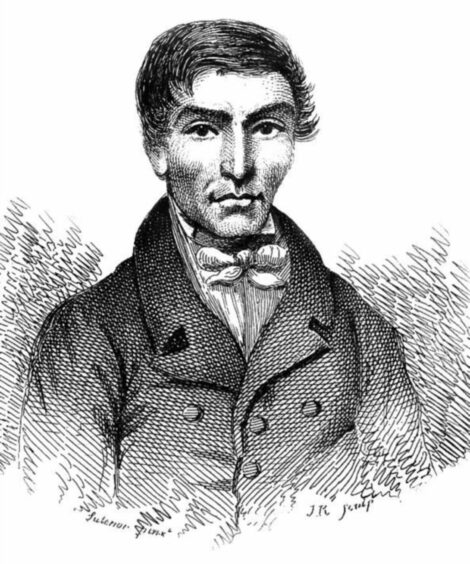

Burke and Hare, both from Ulster, were not body snatchers, as is commonly thought, but cold-blooded murderers.

Once their grisly trade of supplying freshly slaughtered victims to the surgeon Dr Knox for his students’ anatomy lectures came to light, it emerged that they had killed at least 16 people.

They admitted to 13, but were vague about what else they might have done.

Fear and alarm spread throughout the country with every missing person immediately a suspected victim of the grim twosome.

Missing Highland shearers

‘A gentleman’ — unfortunately we don’t know his identity — stoked the flames in the Highlands when he wrote a letter to the Inverness Courier about some missing ‘poor Highland shearers’.

Two centuries ago, destitute Highlanders, many very old women, travelled from Sutherland through Ross-shire and Inverness-shire and on to Lothian to help with the harvests.

They weren’t sheep shearers, but carried shearing hooks, often used for cutting thatch.

The work took them away for six or seven weeks, and once they had paid their transport costs and lost two weeks work travelling, they returned exhausted and almost as poor as when they set out.

The letter to the newspaper doesn’t record who the missing folk were, but they hadn’t reappeared after the harvest, sparking alarm.

The letter-writer appears to have been in a position of some authority as he was able to visit Burke’s lodgings in Edinburgh’s West Port and saw for himself several shearing hooks lying there.

He wrote: “I fear that some of our poor Highland shearers have become victims at the slaughter-house in the West Port, as I observed several hooks lying in Burke’s room which I visited.

Gentleman questioned Burke and Hare

“I yesterday accompanied by a magistrate to see him and asked if he or Hare had destroyed any persons of that class, but he appeared not to recollect.

“I afterwards asked Hare (who is in another cell) how the hooks came there? But the hell-hound scowled a denial of all knowledge of the circumstance, though he coolly admitted the destruction of thirteen persons.”

The gentleman didn’t let the matter go at that, for he returned for another visit to the cells two days later, although he was to be disappointed again.

“I can learn nothing more about the truth of my conjecture respecting the poor Highland shearers.

“I have again questioned Burke on the subject, when, after repeating his former statement, he said, ‘O sir, that dissecting room (referring to the room at his lodgings where they slaughtered their victims) ought to be better looked after’.

“He promised faithfully to us that he would expose the whole infernal business before he left his cell for execution.”

The truth about the writer’s Highland shearers theory never did emerge, but the gentleman appears convinced that they met their fate in the hands of Burke and Hare.

He interpreted Burke’s words to him about the dissecting room as ‘part of his more extensive confession’.

Dr Robert Knox must have known the truth about the bodies he was receiving from Burke and Hare, but he chose to turn a blind eye.

Edinburgh was at the forefront of anatomical study in the early 19th Century, and corpses for medical research could legally be had from those who had died in prison, suicide victims or from foundlings and orphans.

High demand for corpses

But the demand for cadavers was greater than the legal supply, leading to an increase in body-snatching from graves by so-called ‘resurrection men’.

Burke and Hare were aware of this lucrative trade, but they took things a step further.

When a lodger in Hare’s house died, he turned to his friend Burke for advice and they decided to sell the body to Knox for the princely sum of £7/10s.

This must have sown a seed in their minds, for a couple of months later, another lodger took ill, and Hare was afraid this might deter others from staying in the house.

Solution — he and Burke murdered her and sold the body to Knox.

Their killing spree continued from there, as they lured their victims, often sick , drunk or vulnerable people who crossed their paths, to Burke’s rooms and dispatched them there.

Eventually other lodgers alerted the police and their grisly operation came to an end.

Hare turned King’s evidence in return for his freedom and blamed Burke.

He was released the following year and escaped, fate unknown.

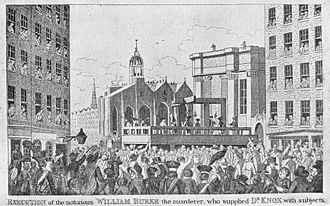

Burke swung from the gallows on January 28 1829, having in turn laid the blame at Hare’s feet.

Their bidey-ins, Margaret Laird and Helen McDougal, who must have known what was going on, managed to escape justice and flee from angry mobs baying for blood.

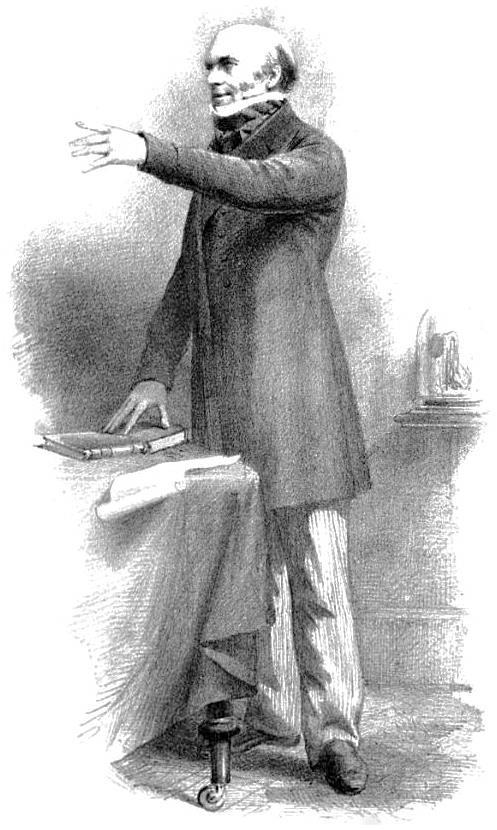

Dr Knox was silent on the matter, and was cleared of complicity.

The Edinburgh mob weren’t satisfied and burned an effigy of him in front of his house, while his peers gradually froze him out of university life.

He went on to lecture throughout Britain and Europe.

While working in London he fell foul of the regulations of the Royal College of Surgeons and was debarred from lecturing.

He was removed from the roll of fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1848.

But nothing was going to stop him pursuing his work as an anatomist.

From 1856 he worked as a pathological anatomist at the Brompton Cancer Hospital and had a medical practice in Hackney until his death in 1862.