If ever you go to Edinburgh Castle to visit the Crown Jewels of Scotland, be aware that one of them is conspicuous by its absence.

You’ll see the Honours of Scotland as they’re termed, in all their glory, the priceless crown made for James V, dating back to 1540, along with the sceptre and sword of state.

There’s the hugely symbolic Stone of Destiny too, with its turbulent past.

So what’s missing? And where is it?

History writer David Willem has been doing some deep research into the missing ‘Black Rood’, a fragment of the so-called True Cross upon which Christ was crucified.

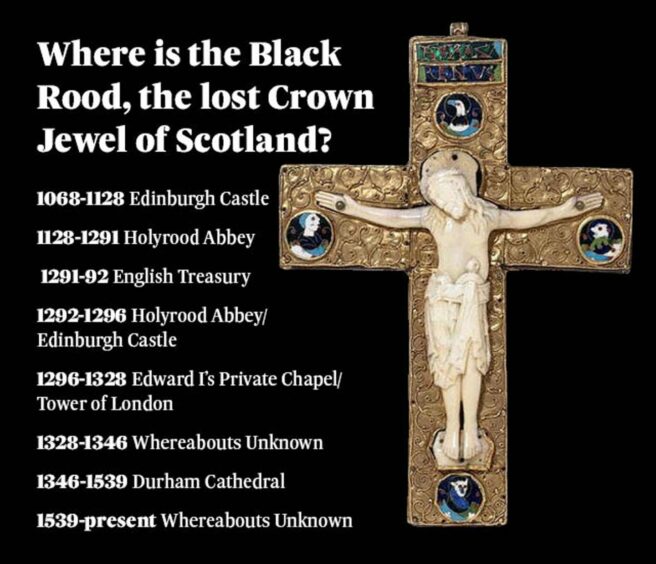

The precious artefact travelled about with English and Scottish monarchs down the centuries, and is thought to have accompanied Edward I as far as Elgin in the 13th century, when he campaigned from Dunfermline northwards via Perth, St Andrews, Arbroath, Montrose, Aberdeen, Elgin and Kildrummy.

David’s book, Black Rood, The Lost Crown Jewel of Scotland (pub. Whittles 2022) paints a vivid picture of how English and Scottish monarchs used the treasure to justify their kingship and to forge their nation’s identity in the Middle Ages.

Hard to prove conclusively the details of the precious fragment’s origins, of course.

David says: “Jesus died in 33AD and the cross was supposedly buried in Jerusalem.

True Cross

“According to legend, Helena, mother of the Roman Emperor Constantine rediscovered the True Cross in Jerusalem in 328AD and took part of it back to Constantinople.

“In 883AD King Alfred of Wessex received a fragment of the True Cross – although this may not have been the Black Rood.”

David picks up the story in 1068, when Margaret of Wessex, fleeing from the Norman invasion of England, brought the Black Rood with her to Dunfermline, where she would marry Malcolm III and become Queen of Scotland.

Pure gold

A 12th Century description of it says it was the length of the palm of the hand, “made with surpassing skill out of pure gold; it opens and closes like a box.

“It bears the image of our Saviour carved from the most beautiful ivory and is marvellously adorned with gold ornaments.”

David was fortunate to be able to access the contemporary accounts of a young priest named Turgot, devoted to Margaret and ultimately author of her biography.

They reveal that Margaret kept the Black Rood near her, most likely at Edinburgh Castle.

Deathbed act

“She asked for it on her deathbed in her final act of piety,” David says. “Her son David I followed the same pattern, keeping the relic near him wherever he went and having it by him on his deathbed.”

We’re familiar with the name ‘Holyrood’, meaning Holy Cross, being attached to the most important religious and royal buildings in Edinburgh.

In our age, Holyrood is the name of our devolved parliament, but it must relate back specifically to the Black Rood, David says.

“David I founded Holyrood Abbey, probably to honour and display the Black Rood.

“It’s speculative, as there’s nowhere you can point to it in the Abbey’s charter, but it seems inconceivable that it wasn’t built for the Black Rood.”

After David I’s death the Black Rood was moved back and forth across the Border by successive monarchs.

Edward I took it to the English Treasury, and then returned it to Holyrood Abbey once he’d decided on his choice for the new King of Scotland, John Balliol.

Repossessed

Back it went to England for another 32 years when Edward invaded Scotland and repossessed it along with the Stone of Scone.

It stayed in Edward’s private chapel, which went on the move with him while he was fighting.

There’s a murky period between 1328 and 1346 when its whereabouts were unknown.

David thinks it may have been returned to Scotland as part of a peace treaty after Scotland’s victory in the first war of independence, or like the Stone of Scone, might never have been returned.

The Black Rood reappeared after the English victory at Neville’s Cross near Durham when it was presented to Durham Cathedral as a trophy.

It resided there for almost two centuries, until the Reformation, and then disaster struck.

It disappeared from Durham, whereabouts unknown, although no record of its confiscation or destruction exists.

Could it be out there somewhere? Check your attics. You never know.

Why was it so important?

Why was the Black Rood so important that monarchs took it with them wherever they went, even to their deathbeds?

David says it was central to justify their claims of Christian kingship.

Once Margaret married Malcolm, the Black Rood passed into the Scottish royal family and became a symbol of the authority and legitimacy of Scotland’s kingship and nationhood.

“If you had a piece of the True Cross it showed your Christian kingship came directly from Christ,” David says.

“The Christian King or Queen was intimately connected with Christ, the King of Kings.

“Because of the power of England, the Scottish, Welsh and Irish monarchs all had reliquaries of the True Cross to help them asset their authority and nationhood.

“David I did better at this than the others. His triumph was to establish Scotland as a country equal to England, and this didn’t happen in Wales or Ireland.”

The image David uses on the cover of his book is that of a late 10th Century Anglo-Saxon reliquary of enamelled gold and walrus task ivory, provenance unknown, under the copyright of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

More like this:

St Edward’s Crown to be re-sized for King ahead of coronation

Conversation