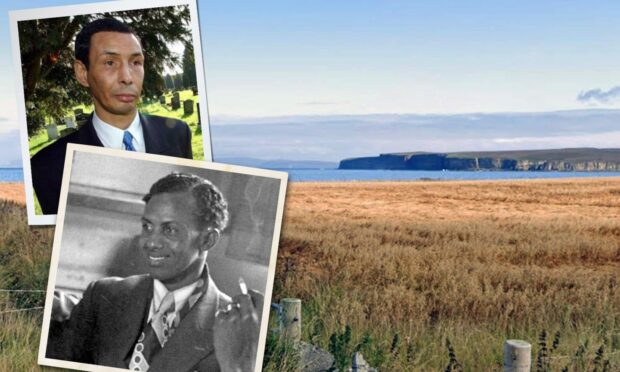

Twenty years ago, a man’s body washed up on a remote Caithness beach under mysterious circumstances.

But this was no ordinary missing person’s inquiry.

It was the latest tragic twist in a tale about the lasting legacy of abhorrent racism, and the infamous miscarriage of justice of Wales’ last hanged man, Mahmood Mattan.

Mahmood was wrongly sent to the gallows in 1952.

The body found on the desolate beach some 50 years later, hundreds of miles from Cardiff, was that of his son Omar.

An open verdict was recorded, but 20 years on, Omar’s daughter doesn’t believe he took his own life.

‘The Man in Black’

Hikers spotted the body on the beach at West Murkle, between Thurso and Castletown, on March 9 2003.

The man found was described as being tall and slim, and having a tanned complexion.

He was smartly dressed in a black buttoned-up coat, black turned-up trousers and a black jumper, with black Clarks shoes.

Next to him lay a half-empty bottle of whisky and a pale blue blanket.

With no identity on his person, and nobody matching his description reported missing, he became known as ‘The Man in Black’.

Detectives admitted they were baffled. How he came to be on the beach was a complete mystery.

The son of last man hanged in Wales

Forensics said the body had only been in the sea for a matter of days.

But nothing indicated foul play, and detectives began to investigate whether the man had fallen off a cruise ship in the Pentland Firth.

Drivers, guest house owners, walkers and fishermen in the Clardon Haven area of Caithness were urged to come forward with any shred of information that might be helpful.

The only line of inquiry officers had to pursue was that the man had undergone a lot of expensive dentistry work.

It would be another four weeks before pathologists identified the man as Omar Mattan – the son of the last man to be hanged in Wales after being wrongly convicted of murder.

In a strange twist of fate, it was through his father Mahmood’s DNA that Omar was identified.

Young family blighted by racism

Somali sailor Mahmood Mattan came to Britain for a better life in the 1940s.

He settled in Cardiff after falling in love with 17-year-old Laura Williams from the Rhondda Valley.

The pair married in 1945 just three months after meeting, and went on to have three sons: David, Omar and Mervyn, who was known as Eddie.

Laura described Mahmood as “a very good husband and father”.

Speaking in 1997, she said: “All he wanted to do was go to work, and he went to sea to earn money until I was having the third child, when he said he couldn’t go and leave me any more and wanted to see the boys grow up.”

The young couple should have been enjoying family life with their little boys in the working-class Tiger Bay area of the docklands they called home.

But they couldn’t even get a home together because of their mixed-race relationship.

Instead, Mahmood had to take lodgings near the docks with other Somali and Jamaican men.

It was typical of the cruel prejudice that would go on to destroy the lives of the Mattan family.

Wrongly charged with murder

The institutionalised racism took a fatal turn in 1952 when Mahmood was executed for a crime he did not commit.

Shopkeeper Lily Volpert was found dead in a pool of blood at her shop on March 6.

The 41-year-old’s throat had been slit. The brutal murder shocked the close-knit community.

In a flawed and desperate investigation, police sealed off the docks – no ship was allowed to leave the port and lodgings were raided.

An unreliable police informer told officers he saw a man leaving Lily’s shop around the time of her death.

He described a tall man of Somali appearance, with a moustache and gold teeth.

Mahmood’s name was given to police and his lodgings were searched.

But he didn’t fit the description, he had an alibi, and there was no murder weapon or motive.

He wasn’t even picked out in an identity parade, yet he was wrongly charged with murder.

The police just wanted a man.

‘I kill no woman’

Mahmood didn’t stand a chance. The whole trial was underlined by racial bias.

He couldn’t speak very good English, and was denied an interpreter in court.

Even Mahmood’s defence solicitor called him a ‘semi-civilised savage’.

Witnesses changed statements and the proceedings took place in front of an all-white jury.

His wife Laura said: “He was convinced they would find out they had made a mistake.

“He couldn’t speak very good English, but he kept on saying, ‘I kill no woman’.”

There was such a dire lack of evidence, that Laura was sure the conviction would be overturned, but he was denied the chance to appeal.

Laura only found out her husband had been hanged when she took their three boys – aged four, two and 16 months – to visit him in Cardiff jail and discovered a notice of his death pinned to a door.

Mahmood protested his innocence to the end.

Family’s decades of anguish ended

Laura embarked on a battle for justice over the next 50 years.

She brought up her boys alone and they too joined the fight to clear their father’s name.

But their lives were overshadowed by racism; they were tormented for ‘being the sons of a killer’.

The family had a breakthrough in 1996 when they were given permission to exhume Mahmood’s body from a felon’s grave at the prison, to be buried in consecrated ground.

His gravestone was etched with the epitaph ‘killed by injustice’.

And finally, decades of anguish ended for the family when Mahmood’s conviction was overturned in February 1998 – Laura was nearly 70.

Three appeal court judges cleared Mahmood’s name after new witnesses came forward and police corruption was exposed.

Tried to drink troubles away

The family received £1.4 million in compensation, but their troubles didn’t end there.

The sons described the payout as ‘blood money’ – it didn’t change the fact their father, an innocent man, was hanged.

David, Omar and Eddie were alcoholics, and family members said it was like they tried to drink the money away.

It wasn’t unusual for Omar to disappear for weeks at a time, but there was deep shock in 2003 when the family learned of his death so far from home.

After an investigation, the Procurator Fiscal found Omar likely got drunk before ending up in the water, but it could not be said whether this was an accident or not.

‘I don’t think he took his own life’

Omar’s daughter Tanya Mattan disputes any suggestion it was suicide.

Speaking to Mattan: Injustice of a Hanged Man Podcast, she said: “I know he always struggled, but he did still seem strong.

“And if he was going to do that why now, why after the conviction had been quashed? It just didn’t make sense.

“It may well be an accident, but something happened and I don’t think it was suicide.

“I don’t think that he took his own life. He just never came across as someone who would do that.”

The months that followed were difficult for Tanya, there were unanswered questions and because of the inquest, the family couldn’t plan a funeral.

A group of Somali seamen in the back room of Berlin’s Milk bar, Tiger Bay, Cardiff c.1950.

Mahmood Mattan sits second from the right.

(1/3) pic.twitter.com/P3FDOPW56a

— The Somali Museum UK (@SomalimuseumUK) September 6, 2020

Tanya added: “I suppose I’m happy it wasn’t a verdict of suicide. I would accept it if I knew that was definitely the case, but there was no evidence to support anything.

“I feel like if it was suicide then I didn’t understand him at all, that I didn’t know him at all.

“I’m not at peace with it.”

Victim of a miscarriage of justice

On September 3 2022, the 70th anniversary of Mahmood’s execution, the family received an apology from South Wales Police.

Chief Constable Jeremy Vaughn said: “There is no doubt that Mahmood Mattan was the victim of a miscarriage of justice as a result of a flawed prosecution, of which policing was clearly a part.

“It is right and proper that an apology is made on behalf of policing for what went so badly wrong in this case 70 years ago and for the terrible suffering of Mr Mattan’s family and all those affected by this tragedy for many years.”

But neither Mahmood’s wife Laura nor their sons lived to hear the apology they had longed for.

Laura died in 2008 aged 78, after years of ailing health.

While none of the three sons made the age of 60; their whole lives blighted by their father’s wrongful conviction.

The circumstances of Omar’s death remain a mystery, as does the true identity of the man who killed Lily Volpert.

Conversation