Sometimes, in the last few years, Jen Stout has found herself in bomb shelters and subterranean facilities, surrounded by death and destruction.

She has watched as women in their seventies slept on cold floors in an underground station and fretted about her, instead of complaining about their own situation.

As she says: “They’d worry about the weight of my flak jacket, my general health, was I eating enough, did I miss my family….it was an overwhelming amount of kindness and solidarity, because we were all in this together, all sheltering from the bangs above.

“Except, of course, I could leave and go back to my peaceful, normal home, and they could not, and that makes you feel terribly guilty, if you dwell on it.”

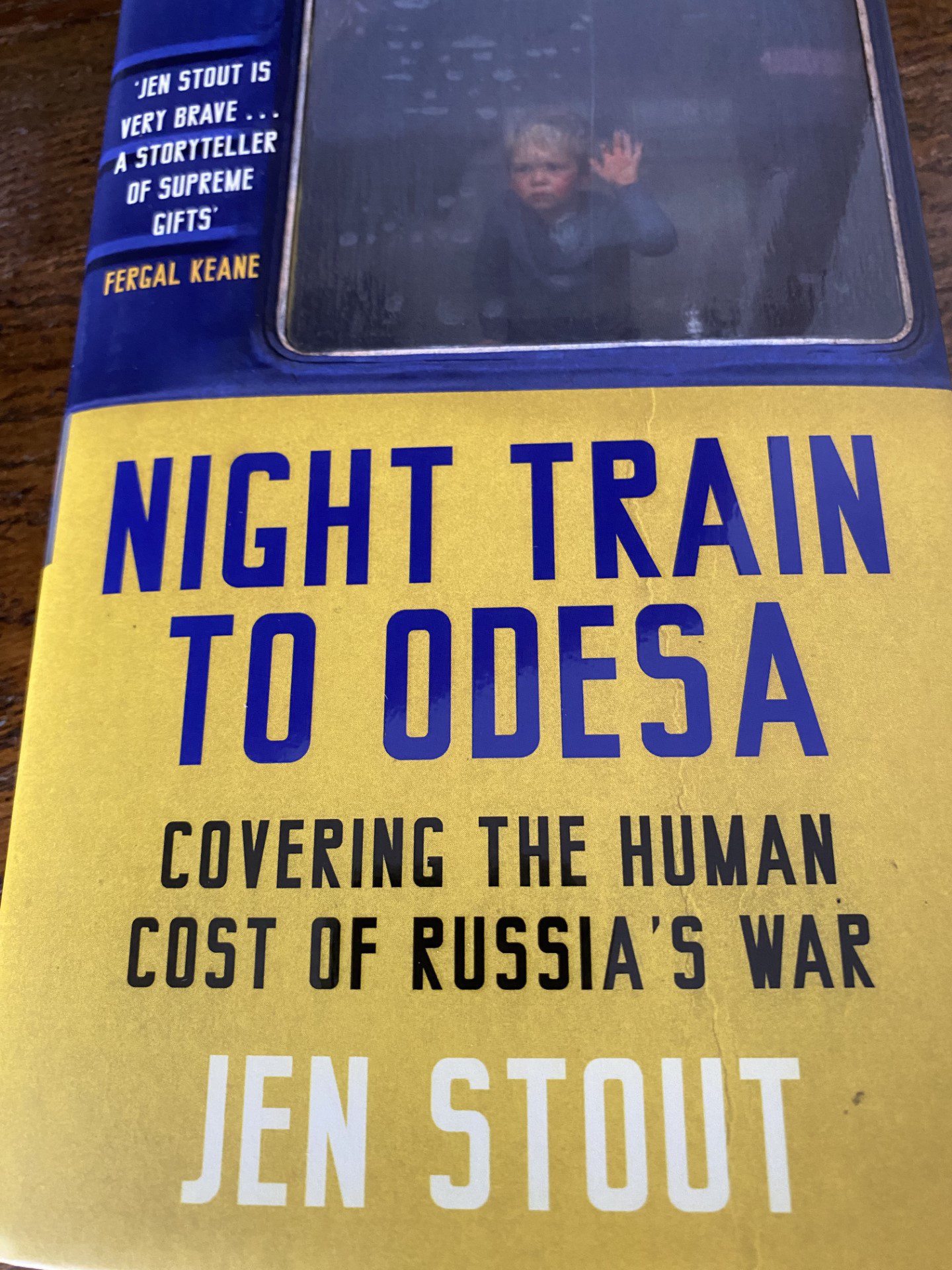

Typically, for somebody with her compassion and empathy for the tragedy unfolding in Ukraine, Jen has dwelt on it in her acclaimed new book Night Train to Odesa.

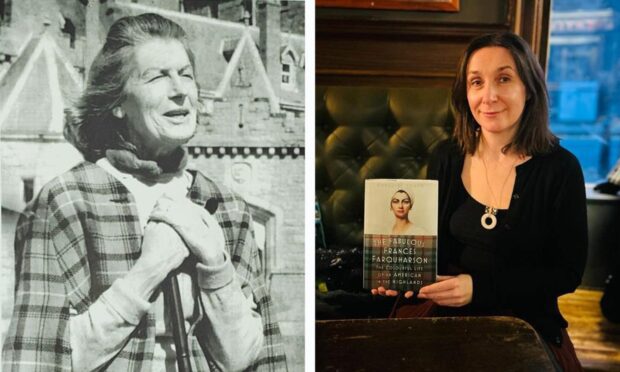

And it explains a lot about how this redoubtable individual has advanced from growing up in Shetland to become one of the most potent war correspondents of her generation.

Her journey has been the opposite of conventional, but Jen’s perseverance has transcended any obstacles. She worked in bars for years – “kind of bitterly”; she began, then abandoned a Sociology PhD; and was “totally derailed” by the death of her mother.

But the spark for writing and journalism was there from a young age and books have always been her solace and escape, allied to her passion for the power of journalism.

‘What a way to spend your days’

She told me: “It hit me when I was studying Russian at 15 in Shetland. I started following the work of Anna Politkovskaya, an investigative reporter at Novaya Gazeta, and was struck by the way she described her reporting in Chechnya – which she must have known would get her killed in Putin’s Russia.

And she added: “I read a lot of Martha Gellhorn and other women reporters in the Second World War, and loved the way they wrote. I thought – what a life! What a way to spend your days. But obviously, you have to do a lot of slog before you can do the things you really want.”

In her case, she did journalism training in Liverpool – “the cheapest option” – and progressed to a local paper in Stranraer. She covered everything from the sheriff court to council meetings and agricultural shows and treasured the value of local news.

After a year, she was hired by the new Nine team at BBC Scotland, and turned her hand to TV producing for a while, then returned to her roots in Shetland and what she describes as “the best radio station in the world.”

‘Radio is a beautiful thing’

She said: “At Radio Shetland, you are presenter, producer, reporter, camera operator. You’re editing programmes and packs, you’re out and about all the time, digging into things. It’s one of the best bits of the BBC, and I loved it there.

“I never set out to be a broadcaster but instantly loved presenting live on air – it felt so immediate and personal, talking to all these people across the isles. Radio is a beautiful thing. Plus it involves much less faffing about than TV.

“But after a year there, I went to Moscow on a funded fellowship. It only took 15 years of trying. But, of course, this turned out to be rather too late.”

The Russian invasion in 2022 changed everything and not for the better. Stout was fascinated by the prospect of covering this at close quarters, but she was smart enough to recognise this couldn’t be just any old assignment.

As she said: “I agonised over the decision. I absolutely didn’t want to be one of those idiots that rushes in unprepared, inexperienced, being a burden on others. People I looked up to told me it would be reckless, stupid and selfish.

A sense of hope and defiance

“But to be totally honest, in my gut I had decided long before the invasion that I’d cover the war. In January 2022, I was in the Moscow flat of a friend, talking about what might happen, and I said out loud that if Russia invaded, I would go to cover the conflict.

“But I didn’t rush in – it was weeks after the invasion that I actually went to Ukraine, and at first just as far as Odesa. It felt fairly safe to be there. In fact, it felt wonderful, arriving on a beautiful spring day, in this city I had dreamed of seeing for years.

“There was a great sense of hope, defiance and common purpose.”

And there was the presence of so many strong, formidable women, whose response to the hostilities was courageous in the teeth of a tempest. Jen marvelled at these females, who kept things together as their world collapsed around them. And even as people she knew and admired perished in terrible circumstances.

She said: “I was so lucky to meet Victoria Amelina. She is a real role model: brave beyond words, determined, full of love, and utterly hilarious.

“I still can’t quite believe she happened to be in that Kramatorsk restaurant when the missile hit – I can’t believe what we’ve lost, in that one senseless act of Russian terror.

‘Women are everything in Ukraine’s fight’

“There was my friend Ivanna in Kharkiv, who has that same determination, that same self-effacing humour as Victoria. I’m trying not to worry about her, because central Kharkiv has been hit by a missile and bomb attack and if I messaged her every time it happened, I’d never give her any peace, so I just wait.

“Women are everything in Ukraine’s fight. Not just those serving, but all those making civil society run, making the trains run, feeding and clothing displaced people, and getting supplies to the front lines. I am in awe of them.”

The trouble is that battle fatigue has set in among sections of the British public and the media. Putin realises this as well. And he can afford to wait.

As Jen said: “One of the myths about the Second World War is that we all hated Hitler from the get-go and were fully behind efforts to stop him.

“But lots of people in this country didn’t give a hoot about the plight of Spain, then of Poland and Czechoslovakia, or the internal victims of the German regime. Eventually, we did collectively back that fight, and helped defeat Nazism, and now the appeasement period is looked on as something quite shameful and dangerous.

‘If Putin wins…he will not stop’

“There are very clear parallels with the current situation. Russia is becoming fascist, is restoring imperial ‘pride’ with territorial conquest. We should have been listening to the Baltic states, to Poland, to Moldova, to Romania, years ago.

“But more than that, we need to understand this is our fight because we are part of Europe, and Europe is under threat from creeping fascism and blunt, brutal military force. Just listen to the Russian rhetoric about Moldova recently – it’s almost identical to their ‘justifications’ for invading Ukraine. If Putin wins in Ukraine, he will not stop.”

It’s a terrifying prospect. But, as Jen Stout has pointed out, people can’t say they haven’t been warned about the consequences of turning their back on Ukraine.

Night Train to Odesa is published by Birlinn.

Five questions for Jen Stout

- What book are you reading? We Saw Spain Die: Foreign Correspondents in the Spanish Civil War by Paul Preston, and The Pilgrimage by Paulo Coelho.

- Who’s your hero/heroine? I always admired Martha Gellhorn’s writing, her life and her outlook on things, but I wouldn’t claim she was without flaws. Though she was a damn sight better than her awful, and much more famous, husband [Ernest Hemingway].

- Do you speak any foreign languages? I speak Russian, a tiny bit of German, and little Ukrainian.

- What’s your favourite band/music? Bongshang. Musical revolutionaries who brought fast Shetland reels and heavy amounts of banjo together with trippy electronica in the 90s and blew all our minds.

- What’s your most treasured possession? Photos of my mum. And my trusty Nikon camera.