After years of campaigning, two retired Uist vets have launched a petition asking the Scottish Government to reconsider the welfare of St Kilda’s sheep.

It’s a debate with the history of a species at its heart.

“It’s taken a long time,” retired Uist vet David Buckland says of the petition that now has over a thousand signatures.

It asks the Scottish Government to “clarify the definition of protected animals contained in the Animal Health and Welfare (Scotland) Act 2006 and associated guidance, to ensure the feral sheep on St Kilda are covered by this legislation”.

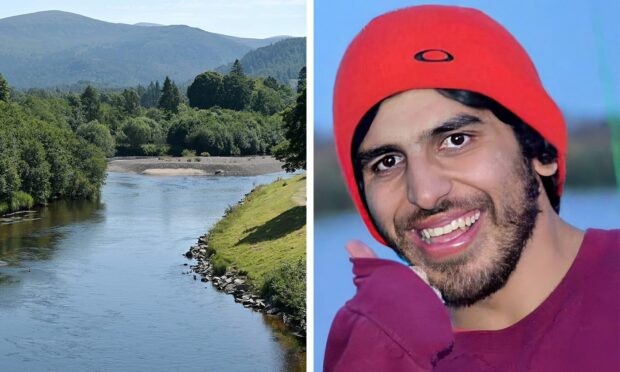

Mr Buckland fellow petitioner Graham Charlesworth have been asking the Government to reconsider the treatment of St Kilda’s sheep since 2017.

Living wild and unmanaged on Scotland’s famous archipelago, hundreds of Soay sheep die of starvation and parasitism every year.

But researchers who study them through the University of Edinburgh’s Soay Sheep Project say it’s a life that, however harsh, is the natural state of an ancient breed.

Is this a case of neglect – or of nature taking its course?

Are St Kilda’s sheep wild?

The sheep living on St Kilda are a rare breed called Soay sheep.

Soay sheep are the same species as other breeds of domestic sheep – Ovis aries.

However, they are very different from modern breeds, as they were domesticated far earlier.

Small and hardy, they resemble domestic sheep’s wild ancestors. The population has lived an isolated life on the island of Soay in St Kilda, scientists believe, since settlers brought them there millenia ago.

They were an important resource for the people of St Kilda, although they were not ‘farmed’ in the modern sense. Instead, islanders made infrequent trips to Soay to collect moulted wool and hunt sheep for meat.

The evacuation of St Kilda in 1930 saw a number of the Soay sheep moved to the now-empty neighbouring island of Hirta.

There, they were left to live wild.

National Trust Scotland describes the sheep as “feral”. Feral animals, like cats, live in the wild but are descended from domesticated animals.

However, Mr Buckland stresses that ‘feral’ does not mean ‘wild’.

“An animal can’t be both,” he says. “To then jump to say that it’s a wild animal or a wild sheep is unscientific.”

What does the law say?

The petition hinges on the Animal Health and Welfare (Scotland) Act 2006.

It says that we have a responsibility to look after ‘protected animals’.

The act specifically mentions that “feral cats, sheep, goats or ponies” are considered protected.

However, it also says that “animals living in the wild which have not had their behaviour, life cycle or physiology altered by being under human control” are not protected.

Soay Sheep Project researcher Professor Dan Nussey says this applies to the Soay sheep because they are “much more similar genetically” to their wild sheep ancestors than modern domestic sheep.

“All evidence suggests the breed’s been living unmanaged and subject to natural selection on the archipelago for considerably more than a thousand years,” he says.

But the petitioners have called this a “legal loophole”.

Officials, Mr Buckland says, have “moved the goalposts” to prevent the feral Soay sheep being covered by the Bill.

Is there a welfare issue?

Both the researchers and the petitioners agree on the fact that large numbers of Soay sheep die each winter.

Their population is limited by the food resources on the island. Rather than holding at a steady number, the population increases to more than the island can support, before dropping steeply due to starvation.

This cycle then repeats in a process scientists call ‘overcompensatory density dependence’.

There’s no doubt that the sheep deaths in St Kilda would be seen as a welfare issue for a typical flock of sheep.

“We are well aware that on mainland hill farms a few sheep may die in winter, ” Mr Buckland and Mr Charlesworth say. But “the scale of the losses on St Kilda is staggering.”

But the researchers of the Soay Sheep Project say that this pattern is seen in some other wild animal populations and is “very much a natural death”.

In fact, says Mr Nussey, compared to many other animals in the wild, “adult mortality rates on St Kilda can actually be rather low”.

“Many sheep on St Kilda live quite long natural lives,” he says. The oldest sheep on record lived to be 16, “considerably longer than you would normally see in domestic sheep”.

He acknowledged that “the way some sheep die on St Kilda during the winter could be considered a bad death”.

“We really don’t take the deaths of these animals or any suffering they experience as part of their natural lives lightly,” he says. The researchers follow the sheep from birth, and are “often saddened by the passing of animals we knew well”.

Why are scientists researching the Soay sheep?

It’s because they are living unmanaged that the Soay sheep are of interest to researchers.

“We monitor the animals as individuals and follow them through their natural lives,” Mr Nussey says.

“It’s one of the longest running and most detailed studies of a large mammal anywhere in the world.”

Because of the “isolated history and the natural behaviour of the species”, he says, the team has made “really groundbreaking discoveries”.

His speciality is “the ageing process in the wild, and also how they respond to climate change and climatic variation”.

Studying the parasites in the St Kilda flock is also providing information about how to combat parasitism in farmed sheep, he says.

Scientists are “trying to move away from” certain drugs used to treat sheep for worms that are resulting in “problematic” resistance.

“Although we’re still at quite an early stage, we’re learning a lot.”

What next?

St Kilda is currently owned by National Trust Scotland.

In a statement, NTS say they will “continue to comply with Scottish Government legislation relating to St Kilda’s sheep populations.”

They are “happy to contribute to any review it decides to undertake”.

Only time will tell if the petition will lead to a policy review.

Even if it fails, though, it’s unlikely Mr Buckland and Mr Charlesworth will give up the campaign.

“Let them call them wild,” Mr Buckland says. “It’s still not right that they should suffer in that way.”

More local reporting from the Western Isles:

Conversation