I can’t stop hearing Sharon Fenty crying as I tell her a sheriff will again fail to meet another deadline to reveal the findings of an inquiry into her son’s death in police custody.

All she wanted to find out was who or what she could justifiably blame for her son’s life slipping away, unnoticed by those in charge of his welfare, nearly a decade ago. Until then, her unanswered questions would haunt her – placing her life in limbo, as the 54-year-old felt prevented from grieving.

Let me be clear: if Warren Fenty hadn’t consumed methadone on June 28 2014, the 20-year-old first-time drug user couldn’t have succumbed to an overdose. But, that said, what followed his decision to take the drug was a perfect storm of circumstances outwith his control that, inevitably, ended in tragedy.

Like all of us at some stage in our lives – particularly during our younger years – Warren made a catastrophic mistake that was to be his last.

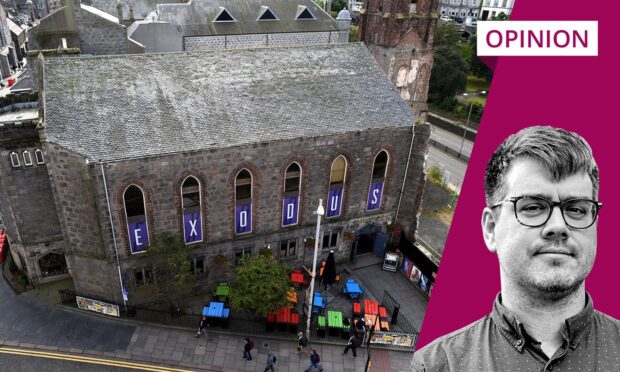

However, the fatal accident inquiry (FAI) into the events leading up to his final moments at Kittybrewster police station’s custody centre wasn’t even about this young man’s error of judgment.

The inquiry actually concerned the mistakes of others, because the “much-loved son, brother and nephew” had already paid the ultimate price, robbing the “lively and loving” Aberdonian of “so many possibilities ahead of him” – according to his devastated family.

This controversial case eventually became Scotland’s longest-ever FAI – and it’s probably one of the biggest scandals in Scottish legal history, too. Let me tell you why.

Delays were both unacceptable and unforgiveable

It only took 12 days to hear the evidence of all 19 witnesses who participated in the Aberdeen Sheriff Court proceedings to determine what led to Warren’s death, followed by three weeks for a sheriff to summarise their testimony and reach his conclusions.

But, Sharon Fenty had to wait almost 10 years to read the report, once it had finally been published. The last evidence included in the report had been taken in February 2022, meaning it took well over two years for someone to write just 39 pages.

As standard practice, the FAI’s hearings couldn’t begin before the Crown Office had prepared the case for court proceedings. But Crown officials appeared to waste around three out of five years, with an inexcusable period of more than three years spent doing absolutely nothing.

Then, much later in the timeline, the original presiding Sheriff Morag McLaughlin missed four deadlines to publish her determination. Her boss – Grampian’s most senior sheriff – was forced to remove and replace her on medical grounds, setting a fifth publication deadline that even he soon failed to deliver.

So, I couldn’t have said it better than Sheriff Principal Derek Pyle, when he began his determination by stating: “The investigation of Mr Fenty’s death has taken far too long.”

But, despite his self-confessed shortcomings during this saga – gracious of him to admit those and explain how he could have done better – the sheriff principal’s no-nonsense approach is possibly the only reason this inquiry ever reached the finishing line.

A monumental show of leadership

Setting the example for accountability at its best, Sheriff Principal Pyle took the unprecedented step of inviting Warren Fenty’s mum Sharon for a private meeting.

He held her hand as he apologised for the distressing way in which the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service (SCTS) had handled her son’s FAI.

Soon after, in the most monumental show of leadership I’ve ever seen from the SCTS, he rightly refused calls to step down over some lawyers’ claims that the closed meeting, which excluded them, had ignored the principles of open justice.

Pyle remained steadfast in the face of potential threats of a judicial challenge to overturn his eventual findings – self-interested threats that I couldn’t see had anything to do with justice.

We’re always told everything is better now

However, don’t be fooled into thinking we needed a £170,000-a-year legal expert to make conclusions you or I could have reached simply with our own common sense.

The compelling evidence in this FAI spoke for itself, with the finger firmly pointing at Police Scotland and its “institutional failings” which led to missed opportunities that, if taken, would “likely” have avoided Warren’s death.

It’s no consolation to Sharon Fenty that, because of major changes to staffing, training, and procedures since her son’s death, someone else’s boy is far less likely to die today.

FAIs take far too long, finishing many years after the incident in question, and we are always told everything is now better

In fact, like Sharon, nothing I read in Sheriff Principal Pyle’s determination was anything I didn’t already know, because, like her, I attended the hearings and heard the witnesses.

That’s the trouble with fatal accident inquiries. They take far too long, finishing many years after the incident in question, and we are always told everything is now better.

When not even a single recommendation for improvement is made, and there’s no mention of any consequences for apparent wrongdoers or their bosses, I worry about the strength of the assurances given, and whether public confidence in them might be misplaced.

Bryan Rutherford is a crime and courts reporter for The Press & Journal and Evening Express

Conversation