The Supreme Court has three options for ruling on a Scottish independence vote, but none of them will be a walk in the park, writes Campbell Gunn.

On Wednesday, we will hear the decision of the Supreme Court in London, which will rule on whether the Scottish Parliament has the legal right to hold another referendum on Scottish independence.

The right to hold such votes is nominally reserved to Westminster, under the terms of the Scotland Act which established Holyrood in 1999. The last referendum was only granted after Alex Salmond and David Cameron agreed what is known as a “section 30” order, temporarily ceding such powers to Edinburgh.

The court has three options. It could rule that the powers are reserved to Westminster, and that Holyrood cannot hold such a vote.

It could decide that, as the vote is merely advisory – as Scottish Government lawyers have argued – it can be organised by the Scottish Parliament.

Or, it could simply decide to take no position on what is clearly a political rather than legal matter. Despite rumours to the contrary, nobody knows what the decision will be.

Whatever the outcome of the court’s deliberations, the decision will have a considerable impact on Scotland’s democratic process.

Democracy comes from the Ancient Greek – “demos”, the people, and “kratos”, rule; a system whereby the people have the right to decide legislation. Like every system of government, it has its flaws.

Winston Churchill once said that it was the worst form of government, except for all the others that have been tried. Mind you, Churchill is also quoted as saying that the best argument against democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average voter. He demonstrated more than a touch of cynicism in both of these viewpoints.

No matter the outcome, Holyrood will have problems

If, as many observers believe, the Supreme Court comes down in favour of the view that the matter is reserved to Westminster, then that indisputably undermines the democratic process, and gives both Edinburgh and London governments a problem.

For Holyrood, it ends any chance of the planned October 2023 referendum, and, at Westminster, the government will have to answer the question of just how a referendum can be legally held if it is supported by a majority of MSPs in the Scottish Parliament, but opposed by the majority of MPs.

That conundrum may give supporters of Scottish independence political ammunition in the long run, but won’t do anything to hasten a vote on the matter in the short term.

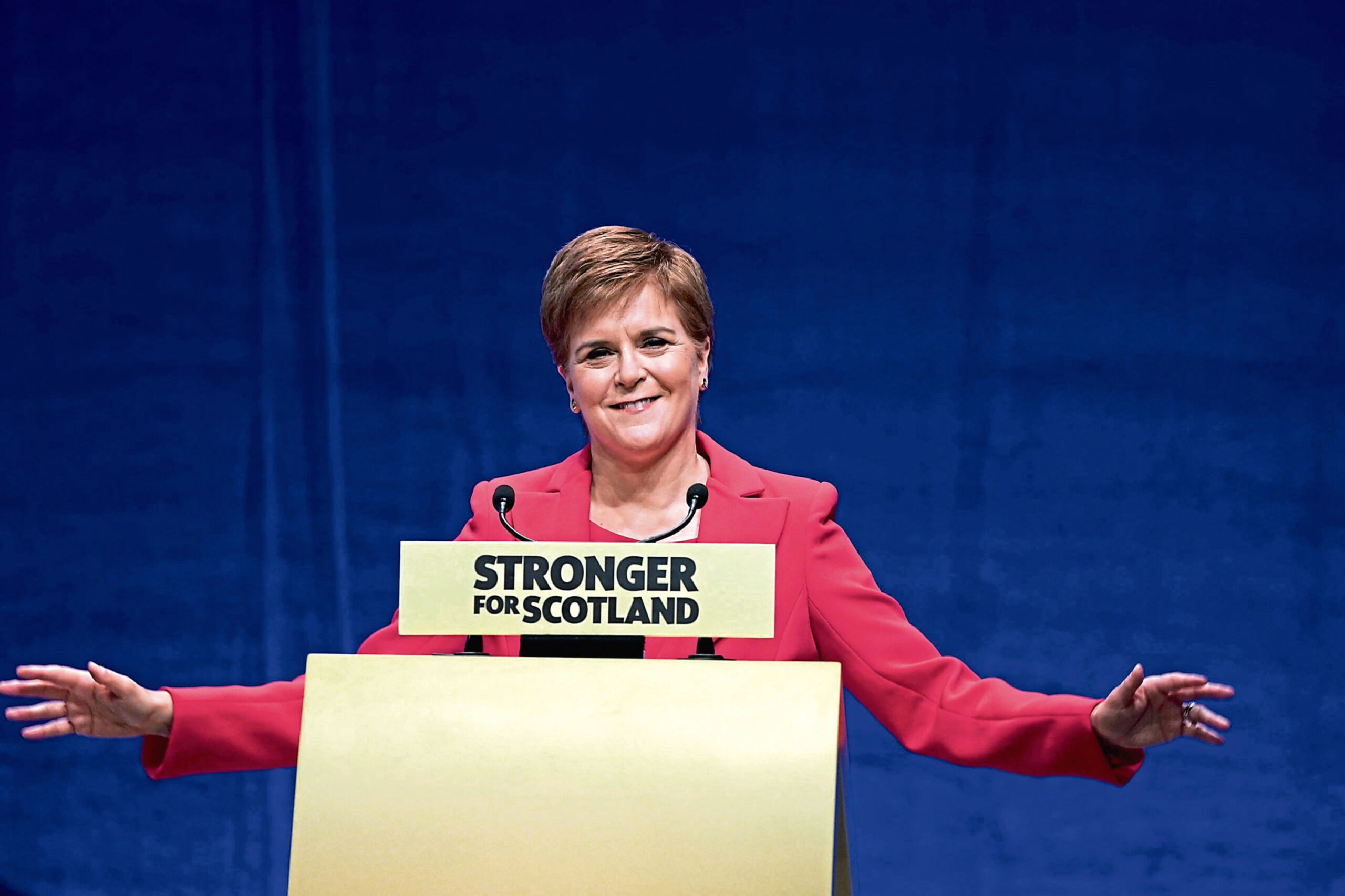

In the event of the court deciding that the Scottish Parliament does have the powers, then the Scottish Government will be faced with another problem. They’ve already said that the referendum, if allowed, will be held on October 19 next year. That gives them 10-and-a bit months to set up and run a campaign.

The Yes campaign for the 2014 referendum was launched in May 2012, with the Better Together campaign begun the following month. We then had over two years to hear the arguments on both sides before the vote was held.

And remember that, in the run-up to 2014, the Yes campaign was a united front, with the SNP joining forces with the many other parties and organisations in favour of independence to campaign side by side. That is hardly the case now, with former colleagues at each other’s throats on social media.

We are unlikely to see certain SNP MPs, for example, campaigning alongside Alba supporters, given what they’ve said about each other. The Yes side is certainly far more fragmented today than it was in 2014.

Brace yourself for a political storm

Worst case of all, perhaps, is that the Supreme Court takes no position on the matter. That leaves the Scottish Government – and parliament – in limbo. Nicola Sturgeon could go ahead with the planned referendum, though a vote in these circumstances would almost certainly face a challenge in the courts over its legality, and the opposition parties could boycott it, making any outcome meaningless.

Whatever the outcome of the court’s decision, Scottish politics is in for a stormy couple of years

And, since the Scottish Government has already argued in court that the proposed referendum is only advisory, not binding, a Yes outcome might face further legal challenges. Indeed, Scottish Conservative leader Douglas Ross has already said that his party will not take part in any referendum which is not legally binding.

We may well see Nicola Sturgeon forced to fall back on her plan B, using the next UK general election as a de facto referendum on Scottish independence, most likely in 2024.

However, to achieve 50% of the Scottish votes in any such election is an extremely high bar, and a very risky strategy. Neither the SNP, nor even Labour at the height of their powers in Scotland, have ever reached it. In fact, the only party do have done so in modern times was, remarkably, the Conservatives in 1955.

Whatever the outcome of the court’s decision, Scottish politics is in for a stormy couple of years. And, as for the chances you’ll be able to exercise your democratic right to vote on Scottish independence any time soon? Don’t hold your breath.

Campbell Gunn is a retired political editor who served as special adviser to two first ministers of Scotland, and a Munro compleatist

Conversation