As Halloween approaches, the perennially popular witch costume will be donned by guisers across the country.

Images of witches have appeared in various forms throughout history – from evil, wart-nosed women huddling over a cauldron of boiling liquid to hag-faced, cackling beings riding through the sky on brooms, wearing pointy hats.

The real history of witches, however, is dark and, often for the women involved, deadly.

Many will know of the Salem witch trials in Massachusetts through popular culture, or perhaps have heard of the Pendle witch trials in Lancashire, or those in North Berwick, famously triggered by King James VI believing a group of women had conjured up a storm that caused his ship to turn back.

But Aberdeen has its own, often overlooked, history of witch hunting – and played a pivotal role in the “panic” which then swept across Scotland.

In 1597, an investigation began into the family of John Leys and his wife, Janet. They were implicated by a woman who had been investigated around Slains a month earlier. Janet was quickly convicted of “harming people through magic” and executed.

John Leys and his three daughters were released or acquitted, but the investigation into the family was seen by authorities in Aberdeen as inadequate, and so a five-year commission to “find and try” all witches in the north-east was approved.

A considerable proportion of the female population died in witch hunt

The city had become convinced it had a serious problem on its hands as a result of the trial of John Leys’s son, Thomas. He confessed – undoubtedly under duress – to having led a coven of witches at a dance at the fish cross the previous Halloween. This was seen as satanic party right in front of the Tolbooth, with demons and dancing.

Thomas implicated a number of other women, and this led investigators to believe that there was a conspiracy or witch “cell” at work in the region.

It took them to the then tiny hamlet of Lumphanan in Aberdeenshire, and then to Buchan. Around 80 people were investigated and 30 women were executed, including nearly a dozen from Lumphanan which, at the time, would have been a considerable proportion of the female population.

Hardly any documents of the events survive, but we can turn to Aberdeen’s extensive financial records for this period to understand the scale of the investigation – and the chain reaction of moral panic the witch hunts triggered.

The monetary outlay was tremendous. The cost of the trials and executions alone reached £165 which was, at the time, equivalent to the entire amount the city would have received from one of its main sources of income, burying wealthy citizens inside St Nicholas Kirk.

200 people were executed in six months

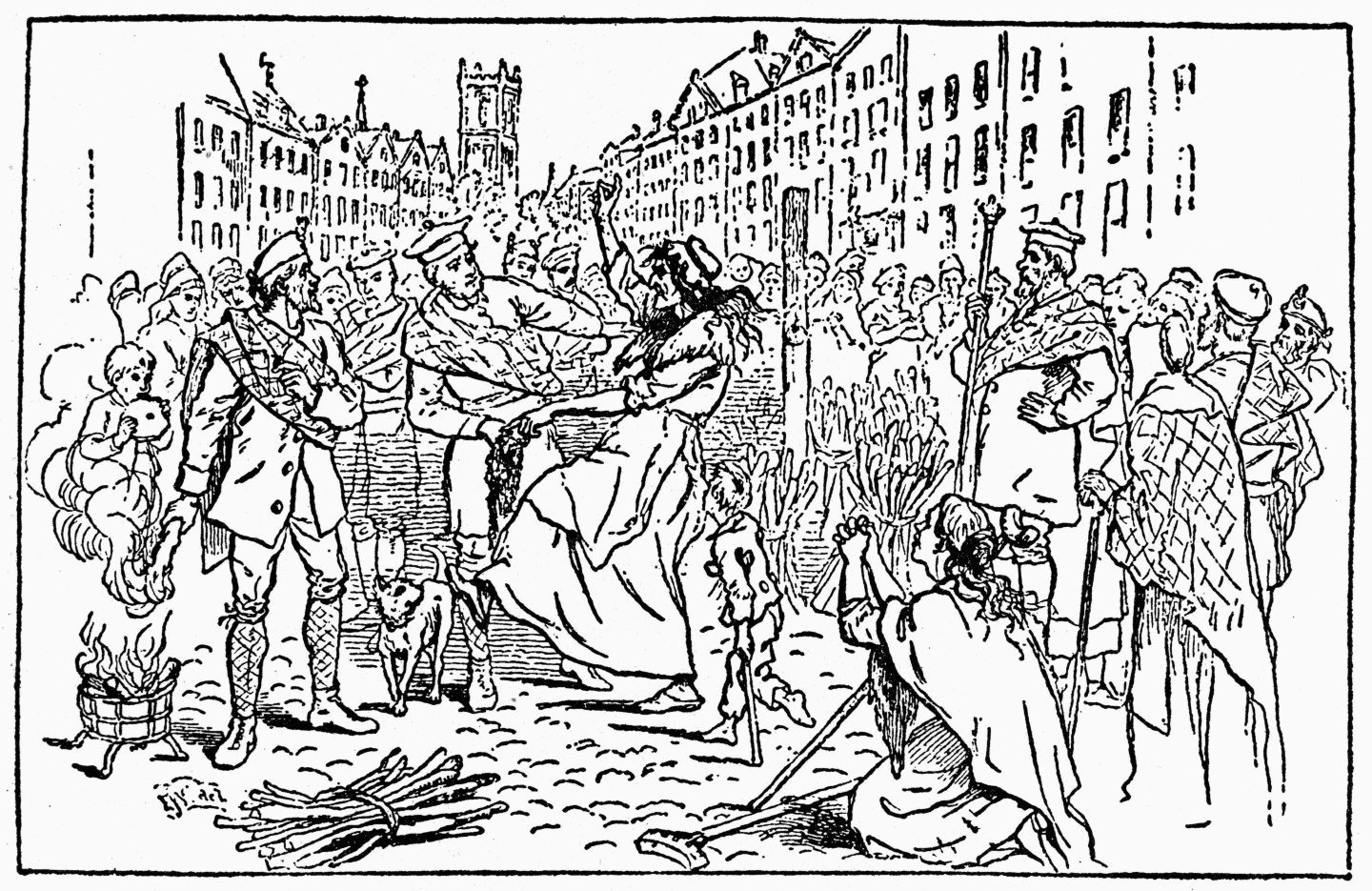

The “panic” that began in Aberdeen in 1597 quickly spread around the country and, in just six months, around 200 people were executed. The usual form of execution for a witch was to be tied to a stake, strangled and set on fire.

This is an important period in our history that should not be overlooked, as it tells us a huge amount about 16th century society. At the University of Aberdeen we are revisiting this history through an online short course, open to people all around the world with an interest in Scottish heritage.

Torture and coercion were key, and methods included sleep deprivation, starvation and thirst, as well as more conventional forms of torture

Those accused of witchcraft faced charges such as flying through the air or worshipping Satan that cannot be proven, only confessed. Torture and coercion were key, and methods included sleep deprivation, starvation and thirst, as well as more conventional forms of torture.

But everyone knew what to confess in the same way that if you were tortured about being abducted by an alien, you would give answers like: “There was a bright light” or “The aliens were little green men”. There were stories around what witches did, so those being tortured knew how to answer to stop the pain.

Panic and profiling continue in our society

When society decided it was facing a conspiracy of witches, it also knew where to look – previous witches, family relations with witches – and what to look for. There was, in the minds of people of 1597, an image of a witch.

Effectively, this was a profile. If you fitted the profile, you might be targeted, but if you didn’t, you were much less likely to be targeted. Profiling was alive and well in the 16th century and was as dangerous and dubious then as now.

By the mid-17th century, most places in Europe stopped prosecuting witches. The last successful prosecution under the 16th Century Witchcraft Act in Britain was in the 1940s. After that, all the Witchcraft Acts were repealed, so it was no longer a crime.

But, while we may no longer seek witches in this way, the lessons of societies’ moral panics and the profiling methods used to detect them sadly remain highly relevant in the world today. It is important that we remember the story behind the costumes and the images of popular culture.

Dr William G Naphy is a professor of early modern history at the University of Aberdeen specialising in the Reformation and social control

Conversation