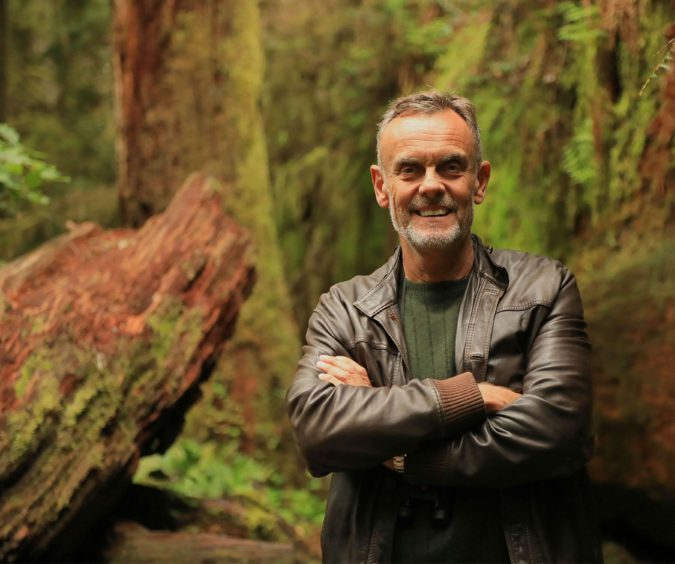

Paul Lister is at the helm of one of Britain’s most ambitious rewilding projects. Gayle Ritchie heads to Alladale Wilderness Reserve to meet ‘The Wolf Man’.

Ancient Scots pines, cascading waterfalls, peaty lochs, heather moorlands, dramatic hills and glens – Alladale Wilderness Reserve is breathtakingly beautiful.

After dinner with owner Paul Lister, I slip out into the night to drink in the atmosphere of this special place, deep in the heart of Sutherland.

It’s midnight in late June and the sky is still light. There’s not a breath of wind and I pause a while to enjoy the rare sensation of complete silence. Of stillness.

Anyone lucky enough to have been to Alladale – and met Paul – will know it’s an intense, but truly amazing, experience.

Paul, who inherited the hugely successful MFI furniture chain, took over Alladale in 2003 with the plan of “rewilding” the 23,000-acre estate.

Formerly run as a traditional sporting estate, it had, in his mind, been depleted of much of its natural goodness over the centuries.

Wild animals that once roamed here, such as wolves, wild cats, bears, boar and lynx, had been wiped out and vast tracts of forest torn down.

Paul, who describes himself as a “wildlands philanthropist”, saw taking on Alladale as his chance to put something back – to give back to nature what mankind had taken away.

“We’ve done this to the land,” laments the businessman-turned conservationist, pointing to a bracken and heather-clad hill.

“Nothing is how it was 500 or 1,000 years ago. It’s like a desert, comparatively.

“This area was once dominated by ancient Caledonian pine forest, and wolves and bears roamed freely.

“When landowners turned Scotland into sheep farms during the Highland Clearances, this changed. Crofters were driven out and forests were chopped down for timber. Large predators were hunted to extinction.

“The barren, bare, hills some view as ‘natural’ are the result of man’s meddling. It’s a man-made landscape; we destroyed the natural landscape.

“Deer – which brought in money – were encouraged to multiply in huge numbers, but too many means forests can’t regenerate because they eat seedlings and kill off older trees by eating the bark.”

Paul’s mission as custodian is to repopulate Alladale with forests, dense swathes of vegetation, and wild animals.

Almost one million trees have been planted so far, there’s a wild cat breeding programme underway, and the reserve teems with wildlife – mountain hares, black grouse, pine martens, red squirrels, trout, otters, ring ouzels, ospreys, peregrine falcons abound, and to my delight, I spot a golden eagle soaring gracefully on thermals.

WOLVES

When Paul shot his first deer aged 20, he questioned his actions.

His thoughts turned to areas of Europe where deer don’t need to be culled in large numbers because natural predators like wolves keep them in check.

Inspired by a game reserve in South Africa, where animals hunted to virtual extinction were reintroduced in extensive enclosures, Paul started looking for an estate in Scotland where he could do the same.

Alladale ticked all the boxes.

“The barren, bare, hills some view as ‘natural’ are the result of man’s meddling.”

Paul Lister

His vision to bring back wolves follows that of Yellowstone National Park in America, where the animals were reintroduced in 1995.

His scheme would involve a controlled release of a pack of wolves that would be tracked and observed.

Miles of red tape and public fear present huge challenges but Paul is ever-hopeful.

“We shot the last wolf in Scotland,” he frowns. “They’ve spread through Europe bar Great Britain and it’s our duty to bring them back. They’ll never get here on their own. People would love to observe wolves year round – it would be a great opportunity for ecotourism.”

The predators would regulate deer numbers on the reserve, mitigating the browsing of young trees and encouraging regeneration.

But the main benefit of the wolf project would be the improvement of biodiversity, a more balanced ecosystem and tourism boost.

To those who fear being attacked, Paul insists wolves aren’t a threat to humans: “They get a bad press because of stories like Little Red Riding Hood. But they won’t be roaming free, turning up in Inverness.

“They’ll be within an extensive enclosure and they’ll acclimatise quickly with all the red deer about. I don’t believe wolves will ever run free around Britain – that’s quite far-fetched with a population close to 70 million. This is the next best thing; it’ll be a trial.

“There’s always someone who’ll say, ‘you can’t do that’, but if the community wants it to happen, it can.”

Seeing the wolf project as something of a “puzzle”, Paul hopes to find like-minded people with which to join forces.

“I could slug away at this myself but I think we need more stakeholders on-board.

“We could create 80 to 100 jobs here, create a wonderful attraction in an area of the Highlands where there’s very little going on, and get more people out of cities into nature. We’ve laid the ground work. Wolves are next on the agenda.”

At one stage, the 62-year-old talked about bringing back bears and lynx, but those dreams have been put aside.

He also ran a scientific project with wild boar but found the creatures couldn’t survive in the environment without shelter and supplementary winter feed.

LEGACY

Paul bought Alladale after his late father Noel, founder of the MFI furniture chain, suffered a stroke two decades ago. A dark period in his life, Paul decided to reinvent himself; to make a lifestyle change – to do something that mattered.

“MFI was not a legacy for my father – it was a means to an end,” he says.

“I’d started off working in warehouses, unloading containers, driving fork-lift trucks, and then got into the retail side of things. There was no joy or passion about it.

“For me, wealth and business isn’t the be-all and end-all. Legacy is about what you do for others or the environment.

“So instead of creating more wealth, I decided to focus on nature conservation, something I’ve always been passionate about.”

Setting up The European Nature Trust (TENT) in 2000 to pursue European nature conservation issues, Paul’s first mission was in Romania, which was being threatened by industrialisation.

His focus soon turned to Alladale where he planned to “restore some life” into the landscape.

LAIRD LISTER

Paul is nothing like the stereotype of a Scottish laird.

During my stay at Alladale, he sports jeans, casual sweatshirts, wraparound sunglasses and trainers – there’s no tweed in sight. He doesn’t enjoy shooting, fishing or whisky.

He’s a juxtaposition of down-to-earth and high in the sky.

When a staff member asks what kind of pillows she should order for guest accommodation and suggests, perhaps, feathers, he baulks. “But guests have a choice!” he exclaims.

Get him talking about the things he loves, the things he’s passionate about, and he shoots out of his seat, arms flailing, eyes wide, and sometimes even does a little dance.

He is energetic, hugely intellectual and unpredictable, bouncing from one subject to the next, his eyebrows shooting up and down and his smile getting ever wider. He’s a likeable fellow.

Paul is not afraid to make his views known, and some have proved unpopular.

One such view is that there should be less people in the world – “I’m concerned about humanity’s ascent; there are too many people and we can’t cope” – and that couples should consider having either one, or no, children.

“In the lifetime of our Queen and David Attenborough, our global population has tripled,” he muses.

“You’d need to be somewhat dim not to realise that’s a problem for the planet. You ignore that fact at your peril. We need to control the growth of population. We’re consuming the planet.”

As I chat to Paul, a thought crosses my mind. MFI made furniture out of millions of precious trees. Is rewilding an effort to assuage his guilt?

He’s quick to the defence, saying: “Ninety-five per cent of MFI’s products were made from chipboard or MDF from managed plantations around Europe. Really, the wild side of me emerged from time spent visiting mills and factories out in nature, and from a childhood of adventure holidays.”

What is obvious is that Paul sees conservation as his life’s work – as his full-time job.

Eccentric he may well be, but Paul has a kind heart and while obviously wealthy, he’s on a mission to help the natural environment, largely through using some of that wealth to make the world a better place. This is his choice.

“I encourage people to explore nature,” he says. “I get people to spend money here which in turn funds environmental, educational and conservation projects and ultimately helps rewild the landscape and help nature.

“I don’t want Alladale to become elitist. It’s not just the rich and famous who come here.

“We fund all sorts of projects for kids so they can be properly immersed in nature.

“It’s not just shooting, hunting and fishing and taking from the land. It’s about giving back.”

WILDERNESS EXPERIENCE

Alladale is a good hour’s drive from Inverness, the jewel in its crown being the imposing Victorian hideaway Alladale Lodge, reached by several miles of winding, bumpy, gravel track.

Stags hang out on the lawn, chomping away happily, seemingly fearless of visitors in this remote territory.

If you want seclusion and rugged beauty, you’ve got it.

There are activities galore on offer, from off-roading with rangers to yoga retreats, cycling tours, meditation and dining experiences, and immersive “wilderness weekends”.

Alladale also hosts a Wif Hom Method retreat, involving vigorous breathing exercises and cold dips in rivers, and an intense survival course backed by Bear Grylls.

Guests can stay in the main lodge or self-catering cottages deep in the glens.

Eagle’s Crag and Ghillie’s Rest are stylish and contemporary while Deanich Lodge, one of the most remote lodges in Scotland, is more rustic.

Perfect for those looking for a truly off-grid experience, the former hunting lodge is seven miles from Alladale Lodge, 19.5 miles from the nearest village of Ardgay, and reached only by a rutted 4×4 track.

Even if you don’t sign up for any activities, it’s wonderful just to “be” here.

On Paul’s recommendation, I head off on a solo jaunt, strolling through heather, woodland and bog to reach pretty Croick Church.

Its beauty belies its tragic past. It was here in 1845 that 18 families who had been brutally evicted from their homes during the Highland Clearances took shelter in the churchyard before seeking sanctuary in the Americas. Some scratched their names and messages on a window to give evidence of the event.

A circuit takes me back to Alladale, and I refresh myself with a dip in a gorgeous wee loch, watched by curious stags.

Later, I enjoy a swim in a secret plunge pool in a river and then sun myself on giant slabs. Bliss.

TREES MAKE TREES

Alladale may be familiar to Springwatch fans – it featured in the BBC series in May and June.

On a 4×4 tour, reserve manager Innes MacNeill points out vast patches of native forest which are regenerating, albeit slowly. “Everything takes so long to grow,” he laments, pointing out some tiny Scots pines.

There’s also birch, aspen, hazel, alder, willow and rowan.

“Trees make trees,” Innes says. “We’re establishing seed sources that are going to future-proof the country. “The oldest Scots pines here are 470 years old.”

I spot them in the distance, a secret forest of gnarled and twisted trunks, like giant Bonsai.

“They’re so old they could’ve had wolves cocking their legs against them!” laughs Innes.

He also points out the “riparian” method of planting along the riverside. This helps shade pools for salmon and stabilises banks, preventing flash flooding.

Red squirrels are thriving here, having been released at Alladale in 2013 as part of a translocation project from the Cairngorms and Morayshire.

Highland cattle have been introduced, and they make great grazers, opening up and fertilising the land.

We pause at the wild cat enclosure to coo at four cute kittens and their mum peeking shyly through a fence.

“Nobody wants to see them in captivity – we want them in the wild eventually,” says Innes.

Alladale’s new aquaponics garden is the latest exciting project, and I’m treated to a peek inside.

It’s designed around a zero-waste recirculating principle: waste produced by rainbow trout swimming in giant tanks is used to feed the plants which in turn return clean water to the fish.

The fruit, veg and salad grown here is served to guests, and it’s a taste sensation, incomparable to anything bought in a supermarket.

LOOKING TO FUTURE

One message Innes, who’s worked at Alladale since 1991, is keen to get across is that the plan is not to “turn back the clocks” here.

“People ask me what the land might look like in 500 years and honestly, I don’t know. I don’t even know what it will look like in 25 years.

“It’s pretty much a blank canvas, with only two to six per cent of the forest left.

“Our ancestors chopped down trees, built houses and ships. We cleared the land.

“This is about legacy and future generations. It’s not a quick fix.”

Like Paul, Innes values “natural capital” above the value of “dead animals”.

He explains how the land here, once valued in terms of deer stalking, salmon fishing and grouse shouting is now valued more for its nature, or, indeed, its “natural capital”, offering ecological and environmental gains that will benefit us long-term.

It would be interesting to come back and chart the changes in five years, 25 years, or even better, next month.

It would be an understatement to say that Alladale has seeped into my soul. I cannot wait to return.

- For more details on Alladale Wilderness Reserve, see alladale.com