In a bid to improve safety on the A9, it was once suggested that lorries should be banned from using the trunk road altogether.

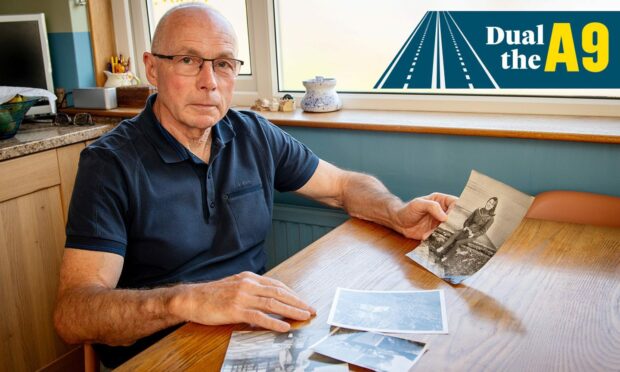

For decades, campaigners have called for the road to be dualled, following hundreds of tragic deaths.

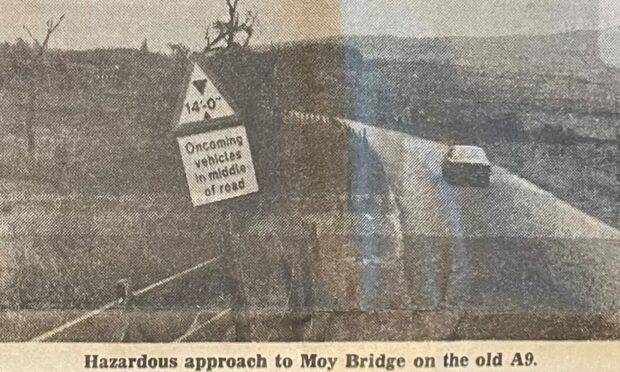

The single-carriageway trunk road was considered obsolete before it was even built, as planners ignored communities’ pleas for a dual carriageway.

A number of ideas have been put forward over the years to reduce fatalities on the road, once dubbed “the killer A9”.

But one of the more madcap suggestions came in 1974: ban articulated lorries from the A9.

A9 vital for Highland industries

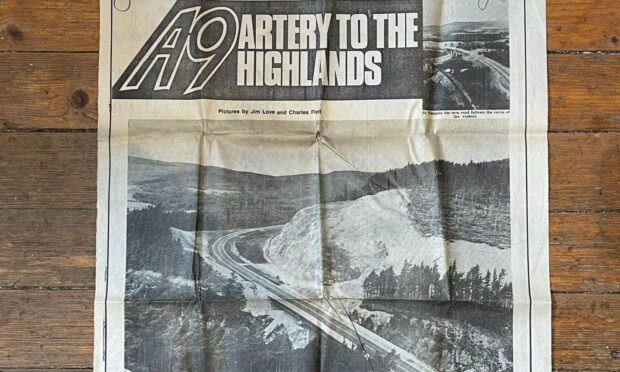

As the main artery of the Scottish road network linking Perth with Inverness and beyond, the A9 was crucial for a number of industries.

The road was a vital route for the transportation of goods by lorry between the Central Belt, the Highlands and Moray.

And apart from tourism traffic, the road was key in supporting the food, drink, forestry and energy industries.

The latter – the discovery of oil – was a driving force in getting the A9 upgraded in the late 1970s.

The Scottish Development Department (SDD) – part of the UK Government’s Scottish Office in pre-devolution days – set up a special project team to speed up the A9 reconstruction in 1974.

The motivation was “to meet new demands created by the oil boom” and make the road more suitable for heavy goods vehicles.

Road upgrade debated in Parliament

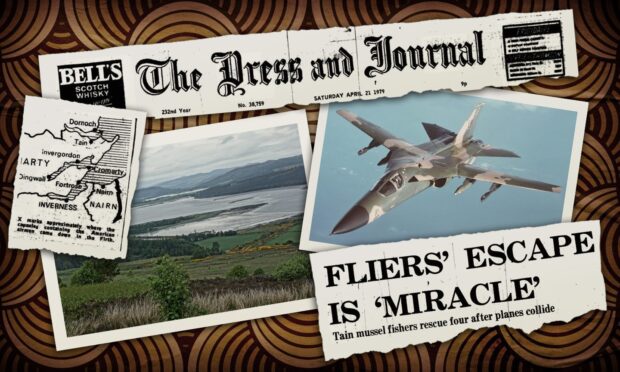

In April 1974, a House of Commons debate centred on Scotland’s burgeoning oil industry and what it meant for A9 improvements.

It was prompted by Hamish Gray, then Conservative MP for Ross and Cromarty, where there was a lot of oil-related development and associated traffic.

David Russell Johnston, then Liberal Democrat MP for Inverness, asked: “Will the Minister reconsider the question of making this road a dual carriageway throughout its length?”

Secretary of State for Scotland, Labour MP Bruce Millan, replied: “The estimated cost was £60 million, but the actual cost will be considerably greater than that.”

He said he hoped the matter would be considered in light of those increasing costs.

Alick Buchanan-Smith, Conservative MP for Angus and Mearns, chimed in: “Does the Minister not realise that the development of this road is fundamental to the development and support of oil generally in that part of Scotland?”

He highlighted press reports that suggested the new Harold Wilson government would scale back A9 plans.

Millan replied: “I am not aware of those reports. I am, however, aware that the road is important for North Sea oil developments, but the expense which the previous Government undertook to meet is likely to be a serious underestimate.”

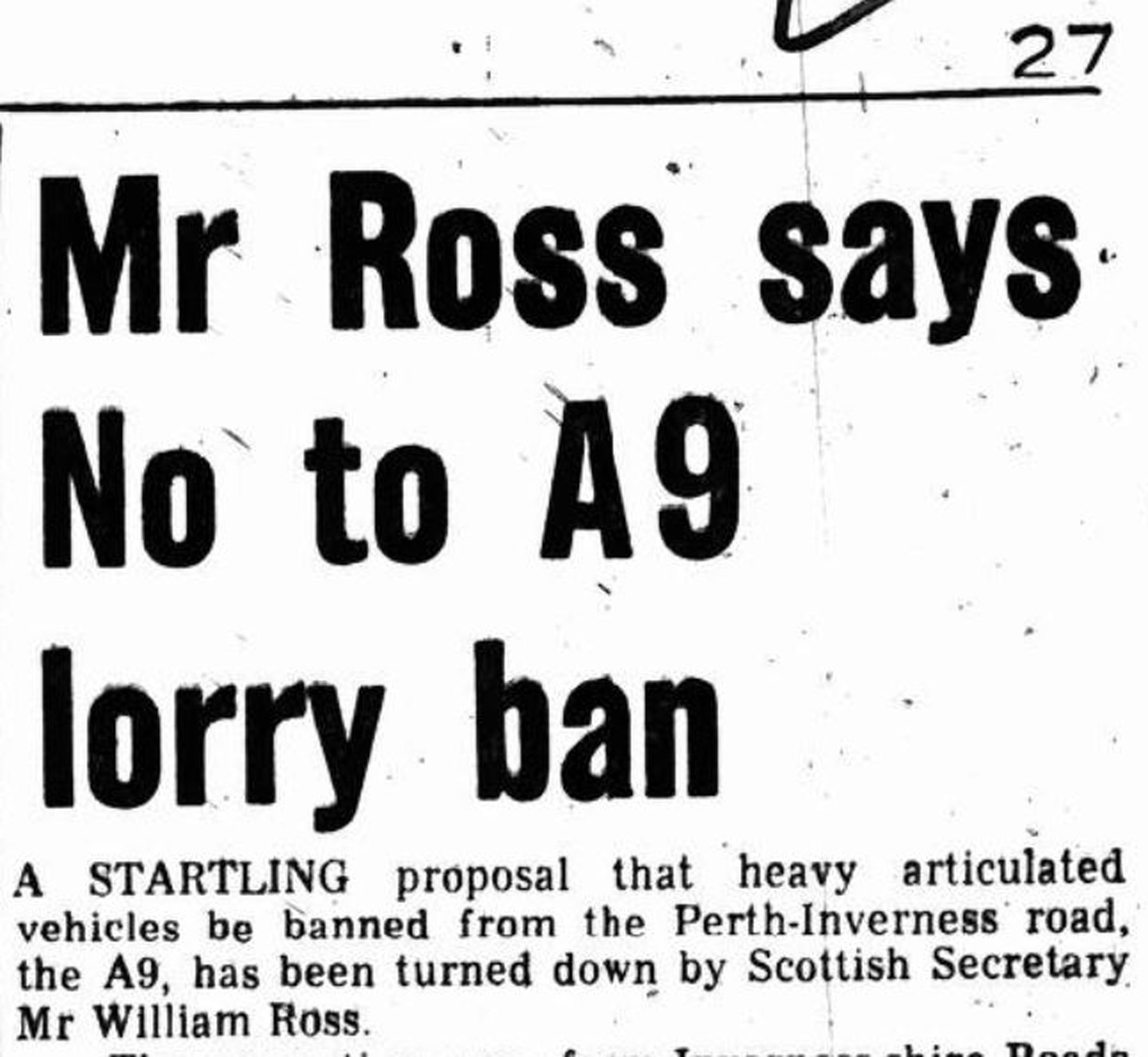

Plan to ban lorries rejected in 1974

With no commitment to dualling, the Inverness-shire Roads Committee put forward its own suggestion.

In September 1974, the committee asked the government to impose a total ban on articulated lorries using the A9 and the A830 – the road through Mallaig.

They said these were two areas of the Highland road network heavily used by lorries.

Described as “a startling proposal”, the Scottish Secretary William Ross swiftly turned down the idea.

The Scottish Development Department doubted whether “apart from the practical difficulties of implementation, such a move would make a significant contribution to road safety”.

It added that “hundreds of thousands of journeys were made each month by vehicles carrying dangerous loads and by articulated vehicles, and though individual accidents received publicity, the accident rate is, in fact, very small”.

Firmly rejecting the suggestion, the SDD went on to state that the limitation suggested by the Inverness-shire Roads Committee would mean detailed control of journeys.

It would also be “complicated by legislation relating to drivers’ hours and would involve quite serious interference with the workings of industry”.

The Department felt at the time that “neither the percentage nor volume of heavy goods vehicles on the A9 was high, and it did not appear to be increasing”.

HGVs ‘more likely to be involved in collisions’

However, when the proposed Beeching cuts became a reality in the late 1960s, it pushed freight off the rails and onto the roads.

And despite the then government’s predictions, the volume of HGVs was indeed increasing.

More recently, Transport Scotland’s case for dualling the A9, released in 2016, said there “are typically 1,300 lorry movements daily on the A9”.

While research by the A9 Safety Group, cited in the Transport Scotland report, said HGVs above 7.5 tonnes “are nearly 3 times more likely” to be involved in a collision on single carriageways of the A9 (Perth to Inverness) section.

Although, at the time of the report, there were fewer crashes on the A9 than other roads in Scotland, the ones that did take place were more likely to be fatal.

Against this backdrop, perhaps banning lorries wasn’t quite as radical a proposition as it seemed.

Does single-carriageway A9 impede freight industry?

But the report also acknowledges the importance of the A9 in the movement of freight.

A survey undertaken in 2014 found 9,738,000 tonnes of goods – from whisky and grain to logs and parcels – was transported by HGVs on the A9 annually.

Converting the volume of that freight into monetary terms equates to around £19 billion a year, proving how vital the A9 continues to be in industry.

While lorries were never banned altogether, various safety measures have been introduced over the years.

These have included average speed cameras, and a pilot scheme in 2014 increasing the speed limit of HGVs from 40mph to 50mph on single carriageway sections of the A9.

The HGV speed limit, along with traffic delays, increases freight journey times.

This takes drivers outwith their allowed limit of hours on the road, meaning deliveries cannot be completed in one shift.

Many have argued that the single-carriageway A9 continues to impede the freight industry, reflecting concerns raised in the 1970s.

Conversation